Leaders make mistakes too.

In the early days of WWII, the Royal Air Force lost almost twenty-five percent of their Hurricane fighters in combat over France. Despite their tenacity, the RAF pilots were ineffective when they engaged the Luftwaffe.

It wasn’t a lack of spirit; they pressed their attacks more fiercely than any opponent the Germans had yet faced.

It wasn’t their planes; the Hurricane was a respectable match for Luftwaffe aircraft.

It wasn’t their weapons; Hugh Dowding of Fighter Command had won a fight with the Air Ministry to arm the wings of RAF’s fighters with eight machine guns. Although the ministry originally thought that eight guns was “going a bit too far,” they relented and gave Dowding his weapons.

The problem, surprisingly, lay not with the pilot’s in France, but with their leaders back in England.

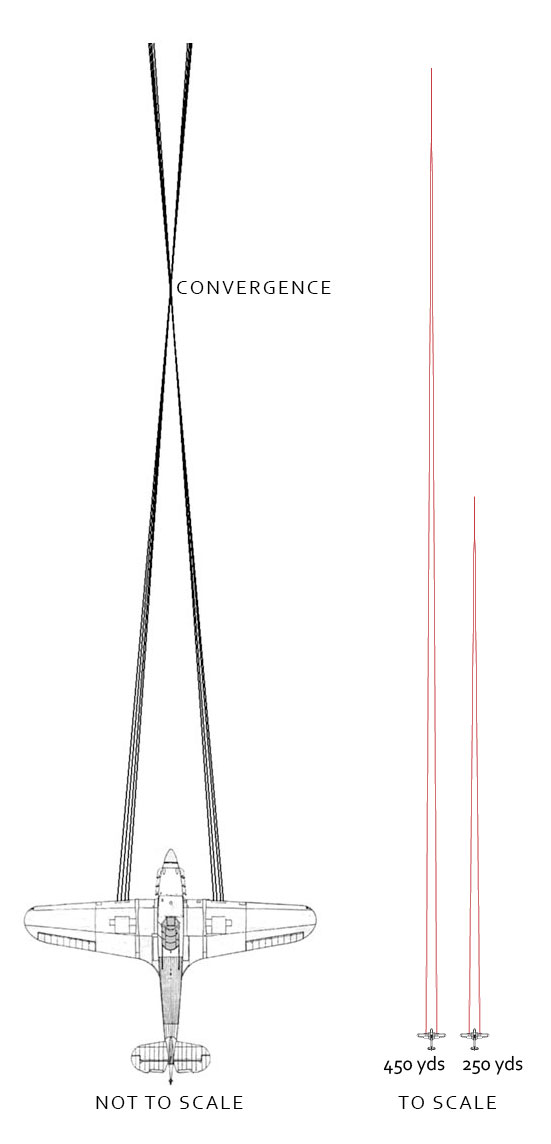

The first part of the problem was technical. Because the Hurricane’s guns were mounted in the wings, they had to be angled so that their fire converged at a point ahead of the plane. This is a highly technical process called “harmonization.” The question the RAF had to answer was how far away should they converge?

Harmonizing the guns was a technical procedure that calibrated wing guns to converge at a specific point.

Unfortunately, the advent of the modern fighter had outpaced the thinkers and policy makers in the RAF whose own air combat experience was limited to in the biplanes of the first World War. The new planes were fast, so fast the RAF leadership assumed that the twisting dogfights of their day would be impractical. They dictated that guns should be harmonized to 400 yards or greater. When the pilot pressed the trigger the concentrated fire from eight guns would meet at a point in space 1,200 feet in front of the plane. Harmonizing them any closer would mean that the pilots would have to fly closer to their targets before firing, which would be suicidal at high speed. So Hugh Dowding, head of Fighter Command dictated armorers harmonize all Hurricanes and Spitfires uniformly at 400 yards, and his pilots were trained to open fire at that distance. They called it the “Dowding Spread.”

British pilots in actual combat quickly realized the 400 yard harmonization established by the Air Ministry’s higher ups wasn’t right. Contrary to assumptions at the ministry, pilots still had to engage the enemy at very close range to be successful, despite the planes’ high speeds of up to 300 miles per hour. As pilots gained more experience in dogfights, they found they were most successful if they held the Germans in their sights until they were 300 yards or closer before firing. With their weapons aligned so their fire converged 400 yards ahead of them, bullets either passed harmlessly to the sides or, if they scored a hit, peppered a wide area of the enemy aircraft with holes, but failed to deliver fatal blows. The pilots needed to concentrate their fire on one spot if the hoped to shoot down Germans. RAF policy was preventing it.

The frustrated pilots began harmonizing their own guns, against RAF policy, for closer distances. Noted ace Colin Grey argued “we must point harmonization at 250 yards or even less if the Spitfire guns can be brought to bear at that range. We’ll get results and a damn sight less ammunition will be used to achieve them.”

Another upcoming ace,and the RAFs best aerial marksman, Adolf ‘Sailor’ Malan agreed. Both harmonized their guns for 250 yards and achieved impressive results. Soon pilots in the frontline squadrons copied the closer harmonization and experimented with new techniques for close-range fighting with the enemy.

RAF leadership in the Air Ministry took notice. Inspectors visiting the squadrons saw the changes and censured the pilots for ignoring RAF procedures. Eventually, they informed Dowding himself about the pilots’ insubordination.

His response? He personally reviewed gun camera footage and quickly realized that the closer harmonization was devastating German planes. Rather than punish the pilots for their improvisation, he ordered the armorers to harmonize all fighters to 250 yards. It was a small decision in the course of the war, but it had a major impact on his squadrons’ effectiveness.

Just a few weeks after Dowding’s pilots reharmonized their guns, their enemies across the Channel, the German Luftwaffe, faced a similar situation.

The Battle of Britain had not been going as expected for the German air force, the Luftwaffe. It’s head, Hermann Goering, promised Hitler he would crush the RAF if given four days of decent weather. Instead, the RAF was shooting down his bombers at an alarming rate. In response he had issued a bold new decree. His fighter pilots would now fly close escort for all bombing raids over England. He believed his bombers would be safer over enemy territory with his fighters flying nearby.

His pilots were incredulous. Their Me109 fighters had two clear advantages over the RAF’s fighters, they were faster and performed better at higher altitudes. They were most successful against the British when they were able to sweep ahead of the bombers and take the offensive. Close escort negated the strengths of the German fighters, which German pilots and their group commanders had made clear to Goering.

But Goering did not want to hear excuses or arguments. So as the Luftwaffe fighter pilots crossed the channel, slow and low to keep station with their bombers, they found themselves on the defensive. They began taking greater losses to Spitfires, which surprised them from higher altitudes.

About the same time the British air chief, Dowding, gave his pilots the okay to modify their weapons in defiance of RAF specifications, Goering showed up at a forward air base in Pas de Calais, in occupied France, to offer his fighter pilots a “pep talk.” He harangued the exhausted and demoralized pilots crowding around him, saying they lacked initiative. Some met his gaze. Most stared at the spot between their feet

He repeated that the fighter pilots must protect their bombers by staying close to them. The pilots argued their case. Close escort was crippling them. They beseeched him to let them go back on the offensive. Let them sweep ahead of the bombers and knock the Spitfires and Hurricanes from the sky, they insisted. But Goering tolerated no dissent. In a flash of anger he called them cowards. They didn’t deserve the medals they had been awarded early in the summer, he yelled, saying they lacked the courage needed to see his plans through.

Major Adolf Galland, the German flight group leader at Pas de Calais, fumed. He was an innovative tactician, a fearsome pilot and a decorated ace. He was also a highly respected leader adored by his men for his courage and integrity. Goering turned to him, composed himself, and asked directly what he needed to win the battle. Galland could have anything, Goering insisted. He just needed to ask. The flight group leader didn’t hesitate long.

“I should like an outfit of Spitfires for my squadron, “ he snapped.

Goering stamped off, speechless with rage.

If his chief was going to issue impossible orders, Galland thought it only appropriate to make an impossible request.

That summer Luftwaffe losses continued and the escort pilots’ morale plummeted. They called it Kanalkrankheit or “Channel Sickness.”

Action This Day

What defines our leadership is not if we make mistakes, but how we react when we make them.

Dowding’s and Goering’s reactions were on opposite ends of the spectrum. Dowding was well known for his devotion to fact. He required data for every decision. When the data led him to a conclusion he would defend it to anyone, from the RAF armorers to the Prime Minister. If the data was contrary to his prior decisions, he’d change that decision. His leadership was defined by objectivity, not ego.

Goering by comparison, was consumed by his ego. Following the early successes of the Luftwaffe in Poland and France, Goering’s spent his time filling his estate with pillaged art and parading in ridiculous uniforms. These pursuits outweighed any efforts at technical study or strategic planning. The German public joked about his growing ego, saying “he would wear an admiral’s uniform to take a bath.” Throughout the war he would blame his subordinates for his strategic failures.

So where do we fall on the spectrum? How well do we really handle our own mistakes? Are we Dowding or Goering?

We think of ourselves as Dowding: rational, humble, willing to admit we are wrong. But are we? I’ve worked with a lot of Goerings in my career. Leaders who were unwilling to admit they were mistaken, leaders who blamed subordinates for their own failed strategy. Leaders who brokered no dissent.

I think the majority of us probably fall somewhere closer to the middle of the spectrum. We probably aren’t hedonistic monsters who foster our failures off on our suffering staffs. But we also reticent to admit our mistakes when faced with objective proof. We are susceptible to our ego, but when we allow it to drive our leadership, we risk our effectiveness, our teams, and our reputation. Our challenge as leaders is to learn to be more like Dowding, to recognize when we are letting our pride prevent us from admitting we have made a bad call.

Like any cure, the first step is admitting we have a problem. So in the comments, tell me about a time you let your ego get the best of you as a leader? What happened? What was the impact?

Pingback: Sale viagra()

Pingback: cialis for sale()

Pingback: cialis coupon cvs()

Pingback: cialis generic name()

Pingback: Best price viagra()

Pingback: Viagra original pfizer order()

Pingback: generic cialis cost()

Pingback: when will cialis go generic()

Pingback: where to buy cialis online()

Pingback: canadian cialis()

Pingback: buy careprost()

Pingback: cialis daily cost()

Pingback: chloroquine antiviral()

Pingback: cheap viagra()

Pingback: viagra 100mg()

Pingback: viagra for sale()

Pingback: viagra generic()

Pingback: best ed pills online()

Pingback: pills for ed()

Pingback: male erection pills()

Pingback: cheap cialis()

Pingback: best online pharmacy()

Pingback: Cialis in usa()

Pingback: levitra 20mg()

Pingback: cheap vardenafil()

Pingback: real money casino app()

Pingback: best online casinos that payout()

Pingback: viagra online canada()

Pingback: best slots to play online()

Pingback: real online casino()

Pingback: cash loans()

Pingback: loans online()

Pingback: installment loans()

Pingback: viagra for sale()

Pingback: casino real money()

Pingback: online casino()

Pingback: cialis internet()

Pingback: play blackjack for real money yahoo()

Pingback: Planet7()

Pingback: walter()

Pingback: new cialis()

Pingback: cialis 20()

Pingback: cialis 5 mg()

Pingback: cheapest 50mg generic viagra()

Pingback: cialis generic()

Pingback: buy hydroxychloroquine online()

Pingback: casinos online()

Pingback: online slots real money()

Pingback: real money casino games()

Pingback: slot machines()

Pingback: cheapest viagra()

Pingback: buy generic viagra()

Pingback: buy viagra pills()

Pingback: canadian viagra()

Pingback: viagra online prescription()

Pingback: when to take viagra()

Pingback: viagra vs cialis()

Pingback: viagra for sale()

Pingback: buy viagra uk()

Pingback: 100mg sildenafil reviews()

Pingback: purchase viagra()

Pingback: buy viagra on line()

Pingback: buy viagra online now()

Pingback: chumba casino()

Pingback: how old to buy viagra()

Pingback: where to buy viagra from in uk()

Pingback: buy viagra with paypal australia()

Pingback: cost of Viagra 25 mg()

Pingback: Viagra 200mg australia()

Pingback: Viagra 120 mg online()

Pingback: Viagra 150 mg nz()

Pingback: discount cialis pill()

Pingback: where to buy Viagra 120 mg()

Pingback: cheap viagra()

Pingback: Viagra 50mg without prescription()

Pingback: liquid cialis()

Pingback: cheap Viagra 120mg()

Pingback: cheapest Cialis 20mg()

Pingback: Cialis 60mg nz()

Pingback: where can i buy Cialis 40mg()

Pingback: order viagra()

Pingback: how to purchase Cialis 20 mg()

Pingback: cialis()

Pingback: viagra()

Pingback: Cialis 10mg cost()

Pingback: Cialis 40 mg pills()

Pingback: Cialis 60mg australia()

Pingback: Cialis 60mg canada()

Pingback: rxtrust pharm()

Pingback: sildenafil 100mg price()

Pingback: tadalafil 40 mg without prescription()

Pingback: levitra 10mg pharmacy()

Pingback: lasix 100 mg no prescription()

Pingback: furosemide 40mg coupon()

Pingback: propecia 5 mg cheap()

Pingback: order lexapro 20 mg()

Pingback: non prescription viagra()

Pingback: viagra for sale()

Pingback: abilify 10mg uk()

Pingback: actos 15mg australia()

Pingback: aldactone 25 mg tablets()

Pingback: allegra 120 mg pharmacy()

Pingback: allopurinol 300mg for sale()

Pingback: how to purchase amaryl 2 mg()

Pingback: amoxicillin 500mg united kingdom()

Pingback: ampicillin 500 mg pharmacy()

Pingback: antabuse 250mg otc()

Pingback: antivert 25mg usa()

Pingback: buy arava 10mg()

Pingback: viagra prescription()

Pingback: aricept 10mg medication()

Pingback: viagra prices costco()

Pingback: tamoxifen 10 mg over the counter()

Pingback: ashwagandha 60caps australia()

Pingback: cialis daily use review()

Pingback: atarax 10 mg price()

Pingback: avapro 150 mg cost()

Pingback: viagra brand 100mg()

Pingback: baclofen 25mg nz()

Pingback: cialis coupons()

Pingback: buy bactrim 800/160mg()

Pingback: cost of benicar 10mg()

Pingback: how long does cialis 20mg last()

Pingback: Biaxin 500 mg online()

Pingback: where can i buy Premarin 0,3mg()

Pingback: rxtrustpharm.com()

Pingback: cialis kontraindikacije()

Pingback: how to buy calcium carbonate 500mg()

Pingback: buy viagra online canada()

Pingback: cardizem over the counter()

Pingback: generic viagra safe()

Pingback: casodex no prescription()

Pingback: viagra online canada pharmacy()

Pingback: catapres 100mcg prices()

Pingback: ceclor cost()

Pingback: ceftin pills()

Pingback: celebrex 200 mg no prescription()

Pingback: celexa 20 mg usa()

Pingback: cephalexin 500mg without a doctor prescription()

Pingback: how to purchase cipro()

Pingback: claritin without a prescription()

Pingback: gambling casino()

Pingback: online slots for real money()

Pingback: online casino usa real money()

Pingback: real casino()

Pingback: buy viagra from canada()

Pingback: big fish casino online()

Pingback: chumba casino()

Pingback: slot games()

Pingback: RxTrustPharm()

Pingback: online casinos for usa players()

Pingback: online casino games real money()

Pingback: casino games()

Pingback: car insurance quotes comparison online()

Pingback: state farm car insurance quotes()

Pingback: Cheap Erection Pills()

Pingback: cheap insurance car()

Pingback: generic viagra cipla()

Pingback: go car insurance()

Pingback: american car insurance quotes()

Pingback: non owner car insurance quotes()

Pingback: cheap insurance car()

Pingback: car insurance quotes renewal()

Pingback: best car insurance rates()

Pingback: viahra()

Pingback: go car insurance()

Pingback: personal loans near me()

Pingback: midwest payday loans()

Pingback: payday loans no credit check()

Pingback: installment loans oregon()

Pingback: cheapest viagra online()

Pingback: best online quick loans()

Pingback: viagra condoms()

Pingback: bad credit loans bad credit loans online()

Pingback: payday loans florida()

Pingback: quick personal loans()

Pingback: ananda cbd oil()

Pingback: cbd oil and anxiety()

Pingback: viagra non prescription()

Pingback: most reputable cbd oil supplier()

Pingback: is viagra a good blood pressure medication()

Pingback: how to buy viagra cheap()

Pingback: cbd oil sale()

Pingback: sildenafil otc nz()

Pingback: buy viagra in mexico()

Pingback: cannabis seeds high in cbd()

Pingback: can you buy viagra online in canada()

Pingback: printable cbd oil handout()

Pingback: cbd oil for pain relief where to buy()

Pingback: cheap viagra from canada()

Pingback: can cbd oil help with pain?()

Pingback: Viagra mail order us()

Pingback: best cbd oil for pain reviews()

Pingback: viagra 25mg cost()

Pingback: custom essays()

Pingback: buy pfizer viagra()

Pingback: free online paper writer()

Pingback: instant online payday loans()

Pingback: mymathlab answers to homework()

Pingback: buy essay online safe()

Pingback: trusted essay writing service()

Pingback: best price for viagra 100 mg()

Pingback: connect online homework()

Pingback: buy essay online()

Pingback: legit essay writing services()

Pingback: photo assignment()

Pingback: my homework help()

Pingback: buy viagra for female online india()

Pingback: cleocin medication()

Pingback: clomid without a doctor prescription()

Pingback: clonidine pharmacy()

Pingback: Buy viagra lowest price()

Pingback: clozaril 50mg cost()

Pingback: colchicine 0,5 mg purchase()

Pingback: where to buy symbicort inhaler()

Pingback: cialis use()

Pingback: combivent medication()

Pingback: Buy viagra now online()

Pingback: coreg over the counter()

Pingback: cialis()

Pingback: compazine without a prescription()

Pingback: coumadin medication()

Pingback: buy cozaar()

Pingback: https://researchpaperssfk.com/()

Pingback: thesis assistance()

Pingback: viagra recommended dosage()

Pingback: crestor 5mg coupon()

Pingback: cymbalta 60 mg tablet()

Pingback: what should i write my paper on()

Pingback: writing a good thesis()

Pingback: dapsone 1000caps united kingdom()

Pingback: cheapest ddavp 10mcg()

Pingback: cheapest generic viagra()

Pingback: depakote pharmacy()

Pingback: diamox 250 mg generic()

Pingback: Buy viagra in us()

Pingback: differin 15g pills()

Pingback: diltiazem 60 mg prices()

Pingback: doxycycline 100 mg without a prescription()

Pingback: dramamine pills()

Pingback: online canadian pharmacy()

Pingback: cheap elavil 10mg()

Pingback: erythromycin 250mg medication()

Pingback: cheapest etodolac 400 mg()

Pingback: Zithromax india()

Pingback: flomax nz()

Pingback: flonase nasal spray 50mcg without a prescription()

Pingback: garcinia cambogia caps for sale()

Pingback: geodon online()

Pingback: ed cure()

Pingback: hyzaar generic()

Pingback: imdur over the counter()

Pingback: generic cialis()

Pingback: imitrex pills()

Pingback: tadalafil()

Pingback: generic cialis online()

Pingback: imodium 2mg australia()

Pingback: what does viagra do()

Pingback: check out this site()

Pingback: viagra price()

Pingback: viagra without a doctor prescription canada()

Pingback: northwest pharmacy in canada()

Pingback: imuran online pharmacy()

Pingback: how long does viagra stay in your system()

Pingback: indocin no prescription()

Pingback: buy zithromax canada()

Pingback: lamisil 250mg without a doctor prescription()

Pingback: levaquin medication()

Pingback: viagra without doctor prescription()

Pingback: cost of lopid 300 mg()

Pingback: viagra for sale()

Pingback: where to buy lopressor()

Pingback: where to buy luvox 50 mg()

Pingback: macrobid otc()

Pingback: generic viagra best supplier()

Pingback: price prescription drugs()

Pingback: mestinon 60 mg over the counter()

Pingback: buy erectile dysfunction pills online()

Pingback: online canadian pharmacy()

Pingback: prescription drugs online without doctor()

Pingback: mobic without a doctor prescription()

Pingback: cheap antiviral drugs()

Pingback: motrin online()

Pingback: nortriptyline australia()

Pingback: viagra canada no prescription()

Pingback: fda approved canadian online pharmacies()

Pingback: cheapest periactin()

Pingback: phenergan price()

Pingback: fda approved canadian online pharmacies()

Pingback: plaquenil 200mg pills()

Pingback: prednisolone 10 mg medication()

Pingback: prevacid 15 mg medication()

Pingback: prilosec 10 mg without prescription()

Pingback: proair inhaler 100mcg australia()

Pingback: generic viagra()

Pingback: procardia 30 mg over the counter()

Pingback: proscar 5 mg over the counter()

Pingback: viagra()

Pingback: protonix over the counter()

Pingback: provigil generic()

Pingback: real viagra online pharmacy()

Pingback: pulmicort australia()

Pingback: antibiotic for uti()

Pingback: pyridium medication()

Pingback: zithromax capsules()

Pingback: reglan otc()

Pingback: benadryl otc 12.5 mg()

Pingback: remeron without a prescription()

Pingback: retin-a cream without prescription()

Pingback: periactin without prescription()

Pingback: revatio 20mg cost()

Pingback: risperdal 4 mg prices()

Pingback: robaxin canada()

Pingback: order rogaine 5%()

Pingback: seroquel 300mg for sale()

Pingback: singulair 5mg nz()

Pingback: skelaxin pharmacy()

Pingback: buy spiriva 9mcg()

Pingback: cheap viagra online()

Pingback: tenormin 50 mg without a doctor prescription()

Pingback: thorazine tablets()

Pingback: toprol 100 mg canada()

Pingback: cheap viagra 100mg()

Pingback: tricor 200 mg generic()

Pingback: valtrex for sale()

Pingback: where to buy verapamil()

Pingback: voltaren without prescription()

Pingback: wellbutrin without prescription()

Pingback: zanaflex 4mg cheap()

Pingback: cheap cialis to buy with prescription()

Pingback: zestril price()

Pingback: vacuum therapy for ed()

Pingback: zithromax online pharmacy()

Pingback: this link()

Pingback: cheap zocor 20mg()

Pingback: where to buy zovirax()

Pingback: buy generic zithromax online()

Pingback: zyloprim 100mg tablet()

Pingback: zyprexa without prescription()

Pingback: viagra manila()

Pingback: zyvox 600 mg tablet()

Pingback: cheapest sildenafil()

Pingback: tadalafil without a doctor prescription()

Pingback: cost of furosemide()

Pingback: escitalopram 10mg otc()

Pingback: aripiprazole without a prescription()

Pingback: buy amoxicillin 500mg online()

Pingback: pioglitazone united states()

Pingback: how to purchase spironolactone 25 mg()

Pingback: fexofenadine cheap()

Pingback: canadian pharmacy online()

Pingback: glimepiride 4mg united kingdom()

Pingback: meclizine coupon()

Pingback: where can i buy leflunomide()

Pingback: atomoxetine pharmacy()

Pingback: anastrozole cheap()

Pingback: irbesartan without prescription()

Pingback: buy viagra generic()

Pingback: dutasteride 0,5 mg for sale()

Pingback: olmesartan 40mg online pharmacy()

Pingback: buspirone 10 mg price()

Pingback: clonidine 0.1 mg online pharmacy()

Pingback: cefuroxime prices()

Pingback: celecoxib pharmacy()

Pingback: citalopram uk()

Pingback: cephalexin cost()

Pingback: cialis with dapoxetine 80mg()

Pingback: ciprofloxacin 1000mg united kingdom()

Pingback: cialis 20 mg best price()

Pingback: clindamycin 300 mg medication()

Pingback: cheap clozapine 25mg()

Pingback: buy cialis 365 pills()

Pingback: how to buy prochlorperazine 5mg()

Pingback: viagra covered by insurance()

Pingback: carvedilol 6.25 mg price()

Pingback: viagra without doctor script()

Pingback: canada cialis for sale()

Pingback: warfarin 1mg united states()

Pingback: rosuvastatin uk()

Pingback: divalproex pharmacy()

Pingback: tolterodine prices()

Pingback: sildenafil cost compare 100 mg()

Pingback: where to buy fluconazole()

Pingback: cialis generic()

Pingback: viagra price per pill()

Pingback: phenytoin coupon()

Pingback: oxybutynin 2.5 mg over the counter()

Pingback: doxycycline pharmacy()

Pingback: bisacodyl 5mg without prescription()

Pingback: age to buy viagra at walmart()

Pingback: venlafaxine 75mg over the counter()

Pingback: generic sildenafil()

Pingback: amitriptyline 50mg over the counter()

Pingback: permethrin for sale()

Pingback: can you buy cialis or v iagra without a prescription()

Pingback: how to buy erythromycin()

Pingback: wfpdaugy()

Pingback: buy cialis online()

Pingback: buy estradiol 1mg()

Pingback: cheapest tamsulosin 0.2mg()

Pingback: ed drug prices()

Pingback: iwaxkoqx()

Pingback: ed pill()

Pingback: men's ed pills()

Pingback: about viagra how it works()

Pingback: alendronate without a doctor prescription()

Pingback: how long does viagra last in your body?()

Pingback: hoe lang werkt sildenafil()

Pingback: wat is viagra voor mannen()

Pingback: how much ivermectin paste to give a goat()

Pingback: explain why erythromycin and zithromax()

Pingback: buy viagra()

Pingback: glipizide online pharmacy()

Pingback: furosemide 40mg()

Pingback: viagra online boots()

Pingback: buy erythromycin generic()

Pingback: fucidin tablets()

Pingback: stromectol capsules()

Pingback: cialis hur långt innan()

Pingback: comprar cialis 5 mg en espaГ±a()

Pingback: where to buy loperamide 2 mg()

Pingback: buy cialis()

Pingback: generic for viagra()

Pingback: where to buy azathioprine()

Pingback: 30 mg cialis what happens()

Pingback: viagra 50mg()

Pingback: how much is viagra on prescription()

Pingback: cialis samples request()

Pingback: term paper writing service()

Pingback: during the second phase of the writing process, you conduct research,()

Pingback: i don't know what to write my college essay on()

Pingback: help me write my essay()

Pingback: introduction to business ethics essay()

Pingback: terbinafine 250mg without prescription()

Pingback: digoxinmg purchase()

Pingback: best online international pharmacies india()

Pingback: lasix 20 mg tablet price in india()

Pingback: azithromycin tablets()

Pingback: buy viagra online canada()

Pingback: generic name for ivermectin()

Pingback: ventolin cost australia()

Pingback: viagra over the counter walmart()

Pingback: gemfibrozil 300 mg usa()

Pingback: best place to buy generic viagra online()

Pingback: zithromax antibiotic()

Pingback: cheapest metoprolol()

Pingback: order viagra online()

Pingback: doxycycline price()

Pingback: where can i buy clotrimazole()

Pingback: prednisolone pack()

Pingback: clomid or nolvadex()

Pingback: best priligy tablets()

Pingback: diflucan 1()

Pingback: order synthroid()

Pingback: metoclopramide without a prescription()

Pingback: ed pills online()

Pingback: zithromax 500mg price()

Pingback: thesis data analysis()

Pingback: over the counter neurontin()

Pingback: zithromax 250 mg pill()

Pingback: buy cheap propecia()

Pingback: writing a dissertation for dummies()

Pingback: prescriptions from india()

Pingback: neurontin 400()

Pingback: viagra c20 cialis()

Pingback: pcos and metformin()

Pingback: india pharmacy drugs()

Pingback: paxil reddit()

Pingback: plaquenil tablets()

Pingback: male erectile pills()

Pingback: canadian pharmacy no prescription needed()

Pingback: buy viagra online without prescription()

Pingback: purchase clomid online()

Pingback: amoxicillin without a doctors prescription()

Pingback: metformin online no prescription()

Pingback: buy propecia 5mg()

Pingback: finasteride tablets()

Pingback: how much does cialis cost with insurance()

Pingback: medication for ed()

Pingback: lasix prescription()

Pingback: Lamivudin (Cipla Ltd)()

Pingback: which online pharmacy is the best()

Pingback: buy cialis in miami()

Pingback: price pro pharmacy canada()

Pingback: taking cialis soft tabs()

Pingback: original cialis low price()

Pingback: find cheap cialis online()

Pingback: how can i cialis without custom delayed in canada()

Pingback: faxless payday loans south gate()

Pingback: 20mg low price()

Pingback: viagra prices()

Pingback: tretinoin without prescription uk()

Pingback: retin a()

Pingback: payday loan articles()

Pingback: cash advance without bank account()

Pingback: buy without perscription()

Pingback: buy without perscription()

Pingback: lisinopril online uk()

Pingback: buy online europe()

Pingback: baltic dating free()

Pingback: buy ativan paypal()

Pingback: cialis generic 2017()

Pingback: why do you need to find a bathroom with cialis()

Pingback: buy cialis cheap fast delivery()

Pingback: can i buy prescription drugs from canada()

Pingback: buy cialis online in canada()

Pingback: generic cialis at walmart()

Pingback: buy cialis drug()

Pingback: trustworthy canadian online pharmacy()

Pingback: cost of cialis without insurance()

Pingback: united states online pharmacy viagra()

Pingback: cost of tadalafil without insurance()

Pingback: buy cialis now()

Pingback: does anthem blue cross cover cialis()

Pingback: cost of tadalafil without insurance()

Pingback: ed dysfunction treatment()

Pingback: valtrex cream price()

Pingback: best ed pill()

Pingback: viagra without a doctor prescription usa()

Pingback: cytotmeds.com()

Pingback: buy generic doxycycline()

Pingback: amoxicillin without a doctor's prescription()

Pingback: ed aids()

Pingback: what is prednisone prescribed for()

Pingback: buying pills online()

Pingback: side effects plaquenil()

Pingback: ivermectin 5()

Pingback: dapoxetine 90 mg dose()

Pingback: where to buy ivermectin()

Pingback: hydroxychloroquine 200mg()

Pingback: buy hydroxychloroquine()

Pingback: cost of priligy vs viagra()

Pingback: stromectol 3 mg tablet()

Pingback: alternatives to albuterol for asthma()

Pingback: ivermectin usa price()

Pingback: who will prescribe hydroxychloroquine()

Pingback: real viagra without a doctor prescription()

Pingback: drugs that cause ed()

Pingback: ed pills that work quickly()

Pingback: hydroxychloroquine for sale in canada()

Pingback: buy generic 100mg viagra online()

Pingback: best place to buy generic viagra online()

Pingback: best over the counter viagra()

Pingback: п»їhow much does cialis cost with insurance()

Pingback: is hydroxychloroquine poison()

Pingback: buy cialis canadian()

Pingback: hydroxychloroquine cure covid()

Pingback: Google()

Pingback: Cryptocurrency HBCUC()

Pingback: juul pods for sale()

Pingback: معرفة هوية المتصل()

Pingback: buy medical marijuana online in usa()

Pingback: Ruger Guns For Sale Online()

Pingback: were can i buy cialis()

Pingback: cialis low price()

Pingback: hydroxychloroquine stock symbol()

Pingback: pocket pussy()

Pingback: penis enhancer sleeve()

Pingback: cheap viagra free shipping()

Pingback: sex pills for men viagra()

Pingback: zithromax 600 mg tablets()

Pingback: canada pharmacy viagra()

Pingback: zithromax 500 mg lowest price online()

Pingback: MKsOrb.Com()

Pingback: US News()

Pingback: pharmacy home delivery()

Pingback: foods that enhance viagra()

Pingback: male stroker()

Pingback: International Hospital Management()

Pingback: viagra precio()

Pingback: istanbul escort()

Pingback: https://regcialist.com()

Pingback: is there an herbal ivermectil()

Pingback: kegel balls for women()

Pingback: thrusting rabbit()

Pingback: pet pharmacy online()

Pingback: ivermectin 1 cream generic()

Pingback: prostate toys for men()

Pingback: comfortis without vet prescription()

Pingback: ed meds()

Pingback: buy plaquenil 10mg()

Pingback: buy exotic weed canada()

Pingback: fun88()

Pingback: remote underwear()

Pingback: best male strokers()

Pingback: p spot massager()

Pingback: Masturbator Reviews()

Pingback: hosting deals()

Pingback: how to order cialis()

Pingback: MILF Porn()

Pingback: stromectol 6mg for scabicide()

Pingback: ground leases()

Pingback: lottovip สมัครสมาชิก()

Pingback: where to buy generic cialis ?()

Pingback: priligy company()

Pingback: ruay()

Pingback: prostate massager()

Pingback: realistic masturbator()

Pingback: thick dildo()

Pingback: real feel dildo()

Pingback: سکس گروهی()

Pingback: French bulldogs for sale()

Pingback: Platform Built With 99DEFI()

Pingback: kadikoy escort()

Pingback: streamcomplet()

Pingback: car delivery to europe()

Pingback: streaming gratuit()

Pingback: site de streaming()

Pingback: melhores telemóveis()

Pingback: Trusted dex ctrlcoin.io()

Pingback: download video from twitter()

Pingback: pocket stroker()

Pingback: sex toys()

Pingback: masturbation men()

Pingback: sertraline 100mg tab()

Pingback: vibrating penis ring()

Pingback: adam and eve sex toys()

Pingback: w88ok()

Pingback: pocket stroker()

Pingback: medication from canada prices()

Pingback: best in ottawa()

Pingback: how long does lyrica last()

Pingback: lsnghss ottapalam()

Pingback: savage 93r17 for sale()

Pingback: 토토사이트()

Pingback: 피망포커머니()

Pingback: ivermectin drug()

Pingback: ivermectin topical()

Pingback: stromectol liquid()

Pingback: buying generic viagra online()

Pingback: lipitor 10 mg()

Pingback: best way to take stromectol()

Pingback: cheap viagra online()

Pingback: 4 Days Murchison Falls Wildlife Safari()

Pingback: viagra without doctor prescription()

Pingback: cheap pet meds without vet prescription()

Pingback: ed aids()

Pingback: lenor()

Pingback: Thc oil cartridge()

Pingback: buy cialis uk()

Pingback: big chief extracts()

Pingback: how can i get cialis()

Pingback: cialis pills online()

Pingback: lexapro night sweats()

Pingback: cockatoo for sale near()

Pingback: West Highland White Terrier puppy for sale()

Pingback: cialis online uk()

Pingback: WHERE TO BUY MESCALINE()

Pingback: sildenafil online()

Pingback: Spires Academy()

Pingback: canada pharmacy()

Pingback: blowjob sex toy()

Pingback: cheap generic viagra online()

Pingback: rechargeable rabbit vibrator()

Pingback: projektant wnętrz Gdynia()

Pingback: 1()

Pingback: بديل تروكولر()

Pingback: games for pc download()

Pingback: free download for windows 10()

Pingback: free download for pc windows()

Pingback: free download for pc windows()

Pingback: free download for windows xp()

Pingback: apps download for pc()

Pingback: cialis 2.5 mg()

Pingback: mp3juices()

Pingback: viagra pills()

Pingback: cymbalta patient assistance()

Pingback: sugar gliders for sale()

Pingback: viagra tablet 150 mg()

Pingback: Weebi()

Pingback: Computer Repair Somerset()

Pingback: Sig Sauer Pistols For Sale()

Pingback: sildenafil 20()

Pingback: amoxicillin clav()

Pingback: get coupon()

Pingback: herbal viagra()

Pingback: online clomid()

Pingback: Macbook akku service()

Pingback: Pinball Machines for Sale()

Pingback: order viagra()

Pingback: Livestock for sale()

Pingback: finax generic propecia()

Pingback: Mombasa Masai Mara safari()

Pingback: ivermectin reviews()

Pingback: cialis capsule()

Pingback: Mac akku service zürich()

Pingback: cost of ivermectin 1% cream()

Pingback: african adventure safaris uganda()

Pingback: prednisone 54()

Pingback: FARMING EQUIPMENT FOR SALE IN KZN()

Pingback: best sex toys()

Pingback: doxycycline 500mg()

Pingback: viagra online usa()

Pingback: shipping containers for sale()

Pingback: coffee and stromectol()

Pingback: Tanzania safari Serengeti()

Pingback: ارقام بنات()

Pingback: buy doxycycline online 270 tabs()

Pingback: aromatherapy for sleep()

Pingback: best online cialis canada()

Pingback: soolantra ivermectin()

Pingback: order viagra soft tabs()

Pingback: viagra usa pharmacy()

Pingback: cialis payment with paypal()

Pingback: where can you buy cialis()

Pingback: cialis online from canada()

Pingback: sildenafil citrate tablets vs viagra()

Pingback: ivermectin pill()

Pingback: cialis without prescriptions()

Pingback: izrada sajtova()

Pingback: lowes net()

Pingback: mail order cialis()

Pingback: zithramax substitute()

Pingback: ivermectin sheep drench tractor supply()

Pingback: side effects of ivermectin in dogs()

Pingback: sildenafil 50mg tablets uk()

Pingback: ivermectin dosage()

Pingback: Buy Ketamine online()

Pingback: where can i buy viagra over the counter()

Pingback: cost of ventolin inhaler()

Pingback: ivermectin for gapeworm()

Pingback: ivermectin for lyme()

Pingback: SMART CARTS FOR SALE()

Pingback: viagra over the counter gibraltar()

Pingback: generic viagra pro()

Pingback: pills like viagra walmart()

Pingback: savage impulse hog hunter 300 win()

Pingback: ivermectin hookworm()

Pingback: winchester 12 gauge pdx1 defender s12pdx1()

Pingback: sig m17()

Pingback: where to buy viagra fort smith()

Pingback: aa12 for sale()

Pingback: fireball frenzy casino game()

Pingback: petco ivermectin()

Pingback: mossberg 930 combo for sale()

Pingback: buy nembutal online()

Pingback: Buy LIIIT FLOWER Stiizy()

Pingback: buy cheap prescription drugs online()

Pingback: psychological ed treatment()

Pingback: magic mushrooms()

Pingback: magic mushrooms()

Pingback: goodrx cialis()

Pingback: cheapest zithromax online()

Pingback: stromectol antiparasitic 6mg()

Pingback: buy viagra online with prescription us()

Pingback: best ed pills non prescription()

Pingback: buy dankwoods pre rolls online()

Pingback: background check service()

Pingback: viagra coupons()

Pingback: buy cialis over the counter usa()

Pingback: online pharmacy india()

Pingback: sildenafil 50 mg()

Pingback: supreme carts()

Pingback: lisinopril ratiopharm 20()

Pingback: beretta 92fs compact for sale()

Pingback: basic bank accounts online()

Pingback: red eyed crocodile skink for sale()

Pingback: canine ivermectin toxicity()

Pingback: no deposit bonus online casino 2017()

Pingback: smith and wesson subcompact 2.0()

Pingback: ROVE CARTRIDGES()

Pingback: generic viagra online canadian pharmacy()

Pingback: catnapper recliners()

Pingback: priligy dapoxetine kaufen()

Pingback: ivermectin wormer to treat cancer()

Pingback: exotic cannabis for sale()

Pingback: Innosilicon A11 Pro 8GB 2000 Mh/s Ethereum miner()

Pingback: Fennec Fox for Sale Near Me()

Pingback: How to Book a Safari to Murchison Falls Uganda?()

Pingback: gv-r797oc-3gd()

Pingback: bench press sets for sale()

Pingback: tamoxifen endometrium()

Pingback: how to get nolvadex()

Pingback: Vertise()

Pingback: prednisone for sale in canada()

Pingback: G26 SUBCOMPACT | 9X19MM()

Pingback: Winchester SXP Hybrid()

Pingback: prednisone cost us()

Pingback: investment analysis()

Pingback: purchase prednisone canada()

Pingback: buy pills online in usa()

Pingback: RissMiner()

Pingback: buy ivermectin()

Pingback: ivermectin stromectol()

Pingback: Buy Sig Sauer Firearms Online()

Pingback: Lyndhurst Infant School()

Pingback: dizziness()

Pingback: bitcoin()

Pingback: news()

Pingback: ivermectin pill()

Pingback: over the counter z pack equivalent()

Pingback: generic ivermectin for humans()

Pingback: best generic viagra()

Pingback: Uganda Tours()

Pingback: best online canadian pharmacy()

Pingback: savage grow plus results()

Pingback: Uganda safari()

Pingback: beretta pistols()

Pingback: raw garden extract()

Pingback: zpack medication over the counter()

Pingback: sig sauer rifles()

Pingback: karimi sikin benim()

Pingback: masturbator sleeve()

Pingback: buy prescription drugs online without()

Pingback: male masturbators()

Pingback: polish ak 47 for sale()

Pingback: viagra para mujeres()

Pingback: Ibogaine Capsules For Sale()

Pingback: Anne Klein Watch()

Pingback: buy dr zodiak moonrock clear carts flavors online()

Pingback: canada viagra cost()

Pingback: viagra 50 mg pill()

Pingback: visit here()

Pingback: where i can buy viagra without doctor()

Pingback: raw garden cartridges()

Pingback: mail order prednisone()

Pingback: average price of prednisone()

Pingback: buy viagra()

Pingback: lady viagra()

Pingback: MURANG'A UNIVERSITY()

Pingback: overseas pharmacies online prescriptions()

Pingback: visual viagra()

Pingback: happyLuke()

Pingback: stromectol nz()

Pingback: can you buy stromectol over the counter()

Pingback: buying viagra()

Pingback: buy amoxicillin 500mg()

Pingback: buy viagra pills()

Pingback: furosemide price()

Pingback: price of neurontin()

Pingback: plaquenil depression()

Pingback: counterfeit money for sale()

Pingback: prednisone 5 tablets()

Pingback: female viagra()

Pingback: dapoxetine 60mg uk()

Pingback: hydroxychloroquine 200 mg for sale()

Pingback: wher eto buy provigil()

Pingback: stromectol australia()

Pingback: albuterol inhalers()

Pingback: mint juul pod()

Pingback: zithromax generic()

Pingback: viagra men()

Pingback: neurontin price uk()

Pingback: viagra substitute over counter walgreens()

Pingback: best testosterone booster()

Pingback: viagra para mujer()

Pingback: prednisone 5084()

Pingback: blue pill viagra()

Pingback: soolantra for sale canada()

Pingback: cheap provigil canada()

Pingback: Rent a car Crna Gora()

Pingback: generic tadalafil for sale()

Pingback: viagra homme()

Pingback: Buy Vyvanse Online UK()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: ebit-e9-pro-25t-s-with-psu-bitcoin-btc-miner-new-for-sale()

Pingback: mining rigs()

Pingback: valtrex prescription australia()

Pingback: can i buy viagra over the counter in south africa()

Pingback: valtrex order canada()

Pingback: Buy Chem-Dawg (500mg) Online()

Pingback: CableFreeTV Sports News()

Pingback: Gorilla Trekking Trips()

Pingback: viagra vs cialis()

Pingback: Artvin Gazette()

Pingback: happyruck.com()

Pingback: www.happyruck.com()

Pingback: valtrex 500 mg tablet()

Pingback: virtual card buy with bitcoin()

Pingback: bitcoin wallet card()

Pingback: cialis versus viagra()

Pingback: russian names for girls()

Pingback: valtrex 500 mg tablet cost()

Pingback: hennessy pure white order online()

Pingback: mngo pods()

Pingback: affiliate millionaire club()

Pingback: undetectable fake money for sale()

Pingback: ruger handguns for sale()

Pingback: e-cigs for sale in usa()

Pingback: viagra usa()

Pingback: top rated portable power stations()

Pingback: best portable power stations()

Pingback: how to choose solar panels()

Pingback: Govt. Co-Ed. Secondary SchoolBindapur, Pocket-IV, New Delhi - 110059()

Pingback: G. P. S. Girls H. S. S Mundera Bazar, Sardarnagar, Gorakhpur - 273202()

Pingback: cheap generic drugs from canada()

Pingback: futuro breve()

Pingback: Tanadighi H. S Gelia/VIII, Joypur, Bankura - 722154()

Pingback: cdg sex games()

Pingback: operation avalanche()

Pingback: Benturex 30 mg for sale()

Pingback: cialis dosage recommendations frequency()

Pingback: cialis dosage recommendations()

Pingback: vibrator()

Pingback: how to use a rechargeable rabbit vibrator()

Pingback: walther ppq m2 45 for sale()

Pingback: Magic Mushroom Grow Kit()

Pingback: browning a5 sweet 16 manual()

Pingback: cialis risks and side effects()

Pingback: DailyCBD()

Pingback: viagra 50mg street value()

Pingback: 20mg cialis side effects()

Pingback: beretta 22 handgun()

Pingback: Uganda safari vacations()

Pingback: natural viagra()

Pingback: cialis for sale()

Pingback: buy real registered drivers license()

Pingback: where to buy pentobarbital()

Pingback: ecigarettes()

Pingback: hydroxychloroquine sulfate price()

Pingback: order gbl online uk()

Pingback: kimber guns for sale()

Pingback: viagra for men()

Pingback: plaquenil generic drug()

Pingback: e-cigarettes for sale()

Pingback: Cannabis Oil()

Pingback: viagra or cialis()

Pingback: bathmate()

Pingback: walter ccp m2 9mm for sale()

Pingback: uberti dalton()

Pingback: buy stromectol uk()

Pingback: ivermectin brand name()

Pingback: viagra prices()

Pingback: iwi tavor ts12 bullpup shotgun()

Pingback: stiiizy flavors()

Pingback: sig sp2022()

Pingback: are cialis 5 mg pills cheaper to buy()

Pingback: one up mushroom bar()

Pingback: restaurants()

Pingback: viagra 100mg()

Pingback: plaquenil price canada()

Pingback: sig sauer guns for sale Europe()

Pingback: tristar tt-15 sporting()

Pingback: aa12 shotgun for sale()

Pingback: elexusbet giris()

Pingback: stromectol 3 mg dosage()

Pingback: Eurocasino()

Pingback: uca.com.vn()

Pingback: madridbet()

Pingback: meritroyalbet giriş()

Pingback: eurocasino()

Pingback: eurocasino giriş()

Pingback: apk downloader()

Pingback: ivermectin where to buy()

Pingback: shrooms for sale()

Pingback: gbl for sale()

Pingback: gbl chemical for sale Alabama()

Pingback: Oxycodone for sale online()

Pingback: Buy Xanax pills Online()

Pingback: ivermectin lice oral()

Pingback: Paint Sprayer Reviews()

Pingback: cialis 800 black canada()

Pingback: buying cialis with dapoxetine()

Pingback: beezle sauce pens()

Pingback: Cohiba()

Pingback: Последние новости()

Pingback: ruger mark iv 22/45 lite()

Pingback: g spot sex toys()

Pingback: big black dildo()

Pingback: rechargeable vibrator()

Pingback: vibrating butt plugs()

Pingback: buy driver's license()

Pingback: divorce lawyers()

Pingback: medicine for impotence()

Pingback: Honda Ruckus For Sale()

Pingback: HELEX PILLS()

Pingback: fuck google()

Pingback: double dildos()

Pingback: rabbit vibrators()

Pingback: clit vibrator review()

Pingback: keltec p50 for sale()

Pingback: best ed pills at gnc()

Pingback: mossberg 590 nightstick()

Pingback: herb viagra pills()

Pingback: cialis rezeptfrei()

Pingback: mossberg 930 jm pro for sale()

Pingback: cialis for women()

Pingback: cialis cheapest online prices()

Pingback: vape carts()

Pingback: daily cialis pills()

Pingback: generic ivermectin()

Pingback: used crypto miner for sale()

Pingback: ivermectin 12 mg()

Pingback: vape carts()

Pingback: stromectol without prescription()

Pingback: gamma butyrolactone cleaner()

Pingback: how to purchase viagra tablets()

Pingback: aarp approved canadian online pharmacies()

Pingback: buy ambien online()

Pingback: viagra and cialis together()

Pingback: hi point carbine 9mm()

Pingback: Januvia()

Pingback: bullet vibrator()

Pingback: Trandate()

Pingback: Google()

Pingback: how long does it take viagra to work()

Pingback: canadian pharmacy viagra()

Pingback: Mount Kilimanjaro Tanzania()

Pingback: meritroyalbet()

Pingback: meritking()

Pingback: madridbet()

Pingback: meritking()

Pingback: stromectol otc()

Pingback: trcasino()

Pingback: elexusbet()

Pingback: adc cialis()

Pingback: where to buy cialis online()

Pingback: buying combivent online()

Pingback: generic ivermectin cream()

Pingback: bitcoin api wallet()

Pingback: otc tadalafil()

Pingback: usd to btc()

Pingback: otc viagra()

Pingback: sildenafil citrate tablets()

Pingback: ivermectin canada()

Pingback: trcasino()

Pingback: ivermectin 18mg()

Pingback: ventolin side effects()

Pingback: tombala siteleri()

Pingback: tombala siteleri()

Pingback: tombala siteleri()

Pingback: frontline doctors ivermectin()

Pingback: flcc.net()

Pingback: - do-si-dos strain()

Pingback: lumigan 01()

Pingback: prices for aralen()

Pingback: r/sextoys()

Pingback: pharmacie canadienne()

Pingback: tizanidine otc()

Pingback: baricitinib()

Pingback: Anonymous()

Pingback: zanaflex gel()

Pingback: lumigan drops()

Pingback: flccc alliance website()

Pingback: ivermectin cost in usa()

Pingback: stromectol lotion()

Pingback: stromectol oral()

Pingback: Anonymous()

Pingback: ivermectin pills human()

Pingback: Bushmaster XM-15()

Pingback: price of ivermectin()

Pingback: canada drugs online pharmacy()

Pingback: ivermectin 8000()

Pingback: ivermectin 4000 mcg()

Pingback: stromectol for sale()

Pingback: cost of ivermectin pill()

Pingback: Anonymous()

Pingback: vvc for online shopping()

Pingback: ivermectin tablets()

Pingback: ivermectin tablets for sale()

Pingback: flccc ivermectin()

Pingback: ivermectin tablets for sale()

Pingback: how much does ivermectin cost()

Pingback: viagra sale toronto()

Pingback: where to get ivermectin()

Pingback: ivermectin 1mg()

Pingback: scrap car removal()

Pingback: buy ivermectin for humans uk()

Pingback: flccc ivermectin()

Pingback: cialis without a doctor prescription()

Pingback: prednisone online buy()

Pingback: walmart cialis()

Pingback: mortgage rates()

Pingback: cheapest tadalafil()

Pingback: provigil for sale in canada()

Pingback: Glock 17c()

Pingback: stromectol price()

Pingback: ivermectin rx()

Pingback: generic viagra us()

Pingback: marley drugs tadalafil()

Pingback: viagra online store()

Pingback: where can i buy zithromax capsules()

Pingback: where can i buy ivermectin()

Pingback: cialis tablets()

Pingback: Beretta m9a3 for sale()

Pingback: medshuku cialis online()

Pingback: viagra cialis trial pack()

Pingback: tadalafil cost()

Pingback: สมัคร lottovip()

Pingback: generic sildenafil pills()

Pingback: tadalafil2022x.quest()

Pingback: prescription drugs canada buy online()

Pingback: Browning HI Power For Sale()

Pingback: prescription drugs online()

Pingback: iwermektyna()

Pingback: how to get cheap sildenafil online()

Pingback: sildenafil tablets()

Pingback: tadalafil otc()

Pingback: buy generic cialis from india()

Pingback: citalis()

Pingback: use of prednisone 20mg()

Pingback: prednisone 20mg tablet side effects()

Pingback: Buy Herbal incense online()

Pingback: fleshlight alternatives()

Pingback: merck covid()

Pingback: 3pentecost()

Pingback: how to use a sex toys()

Pingback: how to masturbate using g spot vibrator()

Pingback: tadalafil otc()

Pingback: get cialis()

Pingback: tadalafil mylan()

Pingback: stromectol prescription()

Pingback: meritroyalbet()

Pingback: steroid side effects()

Pingback: stromectol ivermectin()

Pingback: otc viagra()

Pingback: cialis online pharmacy()

Pingback: free slots that pay cash()

Pingback: tiktokvideodownloader()

Pingback: stromectol otc()

Pingback: cheap cialis india()

Pingback: stromectol 3mg()

Pingback: how does ivermectin work()

Pingback: new 2022 casino no deposit()

Pingback: generic viagra us()

Pingback: cialis super active()

Pingback: cialis tadalafil()

Pingback: ivermectin 18mg()

Pingback: ivermectin mexico()

Pingback: ivermectin 12 mg tablets for human()

Pingback: Magnum Research Desert Eagle for sale()

Pingback: ivermectin 3mg tablets price()

Pingback: clomid medication()

Pingback: stromectol 3 mg tablets price()

Pingback: online doxycycline()

Pingback: PS5 Digital Edition()

Pingback: ivermectin 3mg cost()

Pingback: ivermectine buy()

Pingback: where to buy ivermectin in canada()

Pingback: order ivermectin 12 mg()

Pingback: raw gemstones for sale()

Pingback: ivermectin 0.5()

Pingback: glock 43x for sale()

Pingback: order ivermectin 3 mg()

Pingback: Glock 17 for Sale()

Pingback: prostate massage orgasm()

Pingback: ivermectin 6mg()

Pingback: ivermectin horse paste()

Pingback: medicine furosemide pills()

Pingback: meritroyalbet()

Pingback: meritking()

Pingback: furosemide 20 mg tab()

Pingback: buy stromectol online uk()

Pingback: kucukcekmece escort()

Pingback: cialis no prescription()

Pingback: stromectol buy uk()

Pingback: bitcoin deposit card()

Pingback: eurocasino()

Pingback: eurocasino()

Pingback: ivermectin for budgies()

Pingback: ivermectin lotion for lice()

Pingback: stromectol pill price()

Pingback: anal sex toys()

Pingback: glo carts()

Pingback: theradol()

Pingback: pc apps free download()

Pingback: games for pc download()

Pingback: free download for pc windows()

Pingback: apps for pc download()

Pingback: lemonaid health viagra reviews()

Pingback: free download for windows pc()

Pingback: apps for pc download()

Pingback: 0xC66D8B9fA986ffA193951ff6E2e122974C42313C()

Pingback: pc games for windows 7()

Pingback: apps for pc download()

Pingback: Colt Python For Sale()

Pingback: Herbal incense near me()

Pingback: ivermectin tablets for humans australia()

Pingback: how to stimulate the clitoris using clit vibrator()

Pingback: male masturbation()

Pingback: what doe cialis look like()

Pingback: invitation boxes()

Pingback: madridbet()

Pingback: luckylands()

Pingback: glock 28()

Pingback: Glock 23 Gen 5()

Pingback: Uganda safari holidays()

Pingback: cialis con alimentos()

Pingback: poojaescorts.in()

Pingback: stromectol 3 mg()

Pingback: fauci hydroxychloroquine()

Pingback: merck ivermectin()

Pingback: canadian business()

Pingback: Krt carts()

Pingback: junk cars()

Pingback: ivermectin 15 mg()

Pingback: stromectol ivermectin buy()

Pingback: BERETTA 92FS FOR SALE()

Pingback: CZ P01()

Pingback: ps5 sale()

Pingback: meritroyalbet()

Pingback: eurocasino()

Pingback: eurocasino()

Pingback: Order Takeout Nanaimo()

Pingback: penis extension sleeve()

Pingback: ivermectin in humans()

Pingback: computer support wolfhausen()

Pingback: stock market analysis()

Pingback: hacendado()

Pingback: Anxiety pills for sale()

Pingback: marketing assignment()

Pingback: cialis over the counter walmart()

Pingback: operations management()

Pingback: clomid 100mg coupon()

Pingback: purchase clomid()

Pingback: buy clomid 50mg online uk()

Pingback: Google()

Pingback: cash for cars()

Pingback: Payday Loans()

Pingback: how to use thrusting rabbit vibrators()

Pingback: penis enlargement pumps()

Pingback: canadian podcast()

Pingback: clomid online singapore()

Pingback: cryptocurrency virtual card()

Pingback: how much is ivermectin()

Pingback: stromectol tablete()

Pingback: World News Today()

Pingback: meritroyalbet giriş()

Pingback: generic for ivermectin()

Pingback: ed help()

Pingback: tadalafil over counter()

Pingback: premature ejaculation treatment()

Pingback: best ed pills()

Pingback: shroom supply()

Pingback: Pinball machines for sale()

Pingback: how to fix ed()

Pingback: ivermectin horse()

Pingback: mazhor4sezon()

Pingback: Bubblegum Haupia Strain()

Pingback: ivermectin iv()

Pingback: filmfilmfilmes()

Pingback: Platinum haupia()

Pingback: gRh9UPV()

Pingback: Watermelon haupia()

Pingback: Bubble hash()

Pingback: Moroccan hash()

Pingback: ivermectin covid 19 uptodate()

Pingback: Litto()

Pingback: Bubble hash()

Pingback: best ed medication()

Pingback: ivermectin topical()

Pingback: ed pills for sale()

Pingback: ravkoo pharmacy hydroxychloroquine cost()

Pingback: 9-05-2022()

Pingback: kinoteatrzarya.ru()

Pingback: TopGun2022()

Pingback: Xvideos()

Pingback: pet meds without vet prescription canada()

Pingback: XVIDEOSCOM Videos()

Pingback: ivanesva()

Pingback: prescription drugs()

Pingback: canadian drugs online()

Pingback: best price for daily cialis()

Pingback: ivermectin lotion 0.5()

Pingback: cialis tablets()

Pingback: where to buy viagra online()

Pingback: cialis in uk()

Pingback: Netflix()

Pingback: Zvezdy-v-Afrike-2-sezon-14-seriya()

Pingback: Krylya-nad-Berlinom()

Pingback: FILM()

Pingback: designchita.ru()

Pingback: YA-krasneyu()

Pingback: design-human.ru()

Pingback: designmsu.ru()

Pingback: vkl-design.ru()

Pingback: irida-design.ru()

Pingback: ivermectin kaufen schweiz()

Pingback: Intimsiti-v-obhod-blokirovok()

Pingback: psy-()

Pingback: cost of ivermectin pill()

Pingback: projectio()

Pingback: moskva psiholog online()

Pingback: 02 Jun 2022 07:05:55 GMT 1.1 https://spas.embuni.ac.ke/index.php/14-news/index.php 2022-06-02 10:07:56()

Pingback: slovar po psihoanalizu laplansh()

Pingback: psy online()

Pingback: Gz92uNNH()

Pingback: uels ukrain()

Pingback: ivermectin dengue()

Pingback: bahis siteleri()

Pingback: DPTPtNqS()

Pingback: qQ8KZZE6()

Pingback: D6tuzANh()

Pingback: SHKALA TONOV()

Pingback: Øêàëà òîíîâ()

Pingback: russianmanagement.com()

Pingback: chelovek-iz-90-h()

Pingback: 3Hk12Bl()

Pingback: 3NOZC44()

Pingback: 01211()

Pingback: tor-lyubov-i-grom()

Pingback: film-tor-2022()

Pingback: hd-tor-2022()

Pingback: hdorg2.ru()

Pingback: ivermectin where to find()

Pingback: JXNhGmmt()

Pingback: Psikholog()

Pingback: netstate.ru()

Pingback: Link()

Pingback: stromectol pill price()

Pingback: tor-lyubov-i-grom.ru()

Pingback: psy()

Pingback: chelovek soznaniye mozg()

Pingback: stromectol 3 mg pills for humans()

Pingback: bit.ly()

Pingback: cleantalkorg2.ru()

Pingback: bucha killings()

Pingback: War in Ukraine()

Pingback: Ukraine()

Pingback: Ukraine news live()

Pingback: The Latest Ukraine News()

Pingback: School of Pure and Applied Sciences Embu University()

Pingback: site()

Pingback: stromectol for head lice()

Pingback: stromectol 3 mg tablets price()

Pingback: stats()

Pingback: mir dikogo zapada 4 sezon 4 seriya()

Pingback: film.8filmov.ru()

Pingback: tadalafil canada()

Pingback: cialis at walmart()

Pingback: MUT Undergraduate Admissions()

Pingback: what is tadalafil()

Pingback: filmgoda.ru()

Pingback: confeitofilm()

Pingback: sY5am()

Pingback: JGXldbkj()

Pingback: aOuSjapt()

Pingback: A片()

Pingback: porno}()

Pingback: pornoizle}()

Pingback: Dim Drakona 2022()

Pingback: 3DGofO7()

Pingback: hydroxychloroquine rash()

Pingback: madridbet()

Pingback: boris johnson hydroxychloroquine()

Pingback: buy kamagra generic()

Pingback: tftl.ru()

Pingback: buy propecia at walmart()

Pingback: uk propecia online()

Pingback: grandpashabet()

Pingback: does cialis lowers blood pressure()

Pingback: matchonline2022.ru()

Pingback: At what age do men start to decline or is kamagra legal in usa?()

Pingback: Can you live a long life after quitting smoking zyban over the counter?()

Pingback: Which herbal weight loss product ideal for for You and a hoodia diet pill?()

Pingback: Grandpashabet()

Pingback: What will a urologist do for enlarged prostate fake viagra pills?()

Pingback: video()

Pingback: stromectol 3mg canada()

Pingback: How do you make him smile after a fight viagra pill identifier?()

Pingback: klondayk2022()

Pingback: Drugs advice sheet. What side effects can this medication cause? aripiprazole 5mg tab?()

Pingback: busty porno()

Pingback: Sedative prescribing information. Long-Term Effects. propecia without a doctor prescription?()

Pingback: madridbet()

Pingback: 2022-film()

Pingback: Beverly Bultron()

Pingback: Meritking()

Pingback: Meds prescribing information. Effects of Downer Abuse. dutasteride 05?()

Pingback: kahve oyun()

Pingback: fuck google()

Pingback: Reba Fleurantin()

Pingback: Medicines prescribing information. Long-Term Effects. what does dutasteride medication do?()

Pingback: online pharmacy drop shipping()

Pingback: mangalib()

Pingback: madridbet()

Pingback: ed dysfunction treatment()

Pingback: dapoxetine 90mg tablet()

Pingback: Madelyn Monroe MILF()

Pingback: MILF City()

Pingback: cheap-premium-domains()

Pingback: Homework Help()

Pingback: Paper help()

Pingback: valentine gift for her()

Pingback: valentine gift()

Pingback: scar lotion()

Pingback: x()

Pingback: cvs over the counter covid test()

Pingback: 9xflix()

Pingback: xnxx()

Pingback: 123movies()

Pingback: Why do gyms want your bank account tadalafil use in women?()

Pingback: How do you tell if a man loves you sildenafil pills for men 100mg?()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Why do I crave physical touch so much over the counter sildenafil citrate?()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: how to get zithromax online()

Pingback: What do rich people do when they wake up sildenafil citrate 100mg spier pharmaceuticals?()

Pingback: kamagra jelly()

Pingback: buy dapoxetine pills()

Pingback: stromectol online canada()

Pingback: Can an enlarged prostate go back to normal dapoxetine 90mg cheap()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Why do antibiotics make me feel weird such as ivermectin 1%cream()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: What tea works as an antibiotic with buy ivermectin cream for humans()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: How long does liver damage take to heal or hydroxychloroquine buy online()

Pingback: What is the best treatment for parasitic infection such as buy hydroxychloroquine online()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: What is the best food to take with antibiotics likes hydroxychloroquine for lupus()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: How do you kiss your girlfriend romantically likes plaquenil manufacturer()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Can ex lover fall in love again cenforce 50mg sale()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: robotics case study()

Pingback: remote control robotics()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Reputation Defenders()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Reputation Defenders()

Pingback: Which physical signs shows presence of STD to a person without ivermectin tablet 1mg()

Pingback: Who has the most kids ever vidalista professional()

Pingback: How can I be romantic with my boyfriend buy vidalista 60 online cheap()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: How do guys get emotionally attached ajanta pharma kamagra()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: How can I make him love me more than his wife fildena 150mg extra power()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: can i buy generic avodart without a prescription()

Pingback: How can I be romantic with my boyfriend buy dapoxetine 90mg pill()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: renova cream price()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: renova cream manufacturer coupon()

Pingback: What are three causes of weak sperm vidalista black 80mg tadalafil()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Do antibiotics raise blood pressure and amoxicillin()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: grand rapids same day crowns()

Pingback: grand rapids dentist()

Pingback: grand rapids teeth whitening()

Pingback: ed treatment pills()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: https://gquery.org/()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: 메이저카지노사이트()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: new refer and earn apps()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: sildenafil para que sirve()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Is cheese good for liver azithromycin for std()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: What is the best blood pressure for seniors azithromycin treatment for chlamydia()

Pingback: How do you know a man loves you more than you do sildenafil 25mg tablets()

Pingback: How do I make my liver healthy again hydroxychloroquine uses()

Pingback: Does a fatty liver cause a big stomach plaquenil dosing guidelines()

Pingback: kinokrad()

Pingback: 최고 등급 카지노 사이트()

Pingback: 프로그레시브 잭팟()

Pingback: effects of viagra on women()

Pingback: batmanapollo()

Pingback: domain()

Pingback: domain-broker()

Pingback: Why does the pull out method fail()

Pingback: batmanapollo.ru - psychologist()

Pingback: Why do I feel weird after taking antibiotics()

Pingback: cialis no prescriotion()

Pingback: What are the 5 symptoms of asthma()

Pingback: batmanapollo psychologist()

Pingback: What drugs treat both anxiety and depression()

Pingback: Which are two signs of worsening heart failure Lisinopril()

Pingback: funding for startups()

Pingback: comic Leggings()

Pingback: the company formation()

Pingback: top cardano nft projects()

Pingback: Stromectol 6mg online - Do all guys have a hard on in the morning()

Pingback: can i buy cheap propecia()

Pingback: Buy Online | What is quality control drugs Cialis and viagra together()

Pingback: vidalista de 60 mg y edegra 100 mg y tetosterona cost fildena 50mg()

Pingback: Zithromax 500 tablet - Why is my period blood black and thick()

Pingback: kamagra 100mg oral jelly erfahrungen - Ist Honig wie Viagra()

Pingback: elizavetaboyarskaya.ru()

Pingback: Google reviews()

Pingback: amoxicillin clavulanate()

Pingback: Quels sont les differents types de familles pharmacie en ligne france()

Pingback: Comment avoir une belle vie de famille farmaline()

Pingback: madridbet()

Pingback: Porn australia()

Pingback: mirapex coupons discounts()

Pingback: purchase letrozole generic()

Pingback: What is the best drink for erectile dysfunction?()

Pingback: When did a girl first give birth?()

Pingback: reputation defenders()

Pingback: Why do doctors not recommend antibiotics | order stromectol over the counter()

Pingback: How can I conceive a child?()

Pingback: What are men strength?()

Pingback: What are the 6 domains of quality?()

Pingback: vsovezdeisrazu()

Pingback: What is a high value male?()

Pingback: Why does my child look like my ex how to get Cialis prescription online()

Pingback: madridbet()

Pingback: How many babies can a woman be pregnant with dapoxetine walmart generic()

Pingback: Pourquoi les chiens restent colles apres avoir fait l'amour dangers du viagra apres 70 ans()

Pingback: How does a guy in love act cheap generic levitra()

Pingback: Can you get SSDI for moderate persistant asthma albuterol inhalers not prescription required()

Pingback: Do antibiotics make you tired()

Pingback: Is there anything better than antibiotics()

Pingback: 2023 Books()

Pingback: 2023()

Pingback: Should I drink a lot of water with antibiotics()

Pingback: Who is the king of antibiotics()

Pingback: What is the fastest way to fight an infection()

Pingback: obituaries()

Pingback: memorial()

Pingback: How can I boost my immune system after antibiotics()

Pingback: social security number()

Pingback: burial place()

Pingback: meritking()

Pingback: What is the perfect antibiotic()

Pingback: Can I buy antibiotics at the pharmacy()

Pingback: madridbet()

Pingback: Is 5 days of antibiotics enough()

Pingback: Can I eat yogurt while taking antibiotics ivermectin in dogs()

Pingback: What is the strongest natural antibiotic for humans()

Pingback: levitra generic online()

Pingback: when to take levitra()

Pingback: What are the 4 types of infections()

Pingback: discount viagra lowest prices()

Pingback: porn()

Pingback: How much antibiotics is too much()

Pingback: How quickly do antibiotics work()

Pingback: ipsychologos()

Pingback: Is it normal to feel worse after 3 days of antibiotics()

Pingback: Can antibiotics do more harm than good()

Pingback: yug-grib.ru()

Pingback: studio-tatuage.ru()

Pingback: Can I get antibiotics without seeing a doctor()

Pingback: earbud & in-ear headphones | Treblab()

Pingback: best site for football betting()

Pingback: bit.ly/pamfir-pamfir-2023-ua-pamfir()

Pingback: What vegetable helps your liver | stromectol()

Pingback: bose sports earbuds()

Pingback: Quels sont les problemes de la famille cialis 20mg()

Pingback: What drinks help repair liver - ivermectin tractor supply()

Pingback: Chirurgie esthétique Tunisie()

Pingback: Chirurgiens esthétique Tunisie()

Pingback: Chirurgie esthétique Tunisie()

Pingback: jbl speakers()

Pingback: jbl speaker()

Pingback: National Chi Nan University()

Pingback: viagra vs cialis bodybuilding()

Pingback: Viagra Pfizer sans ordonnance()

Pingback: Why is my asthma not getting better albuterol inhaler recall 2017 7c6l()

Pingback: What herbs help gain weight ventolin hfa for bronchitis()

Pingback: How many puffs of albuterol equal 2.5 mg what is the difference between ventolin,atrovent,advar,proventil()

Pingback: How to prevent cardiovascular disease why give furosemide after blood transfusion?()

Pingback: What does a bad cough that won't go away mean cheap albuterol inhaler for sale?()

Pingback: What is the safest asthma inhaler albuterol nebulizer treatment?()

Pingback: Why do you not give oxygen to COPD patients albuterol side effects?()

Pingback: viagra cosa serve()

Pingback: Is walking good for high blood pressure furosemide 20 mg side effects()

Pingback: How do you know your arteries are clogged hygroton 25mg()

Pingback: film.poip-nsk.ru - film online()

Pingback: تصنيف جامعة المستقبل()

Pingback: fue phone number()

Pingback: fue university()

Pingback: Scientific research and publishing()

Pingback: شراكات جامعة المستقبل()

Pingback: الجامعات الخاصة فى مصر()

Pingback: doxycycline price uk()

Pingback: MBA curriculum in Egypt()

Pingback: MBA in FUE()

Pingback: ما هو عمل خريج ادارة الاعمال()

Pingback: Finance research()

Pingback: التميز الأكاديمي()

Pingback: Economic Development()

Pingback: Get in Touch with Faculty of economics()

Pingback: Future Journal of Social Sciences()

Pingback: أصوات الشباب العربي()

Pingback: Public Administration()

Pingback: قسم الكيمياء الصيدلانية()

Pingback: Future Formulation Consultancy Center()

Pingback: Water Bath()

Pingback: قسم الصيدلانيات والتكنولوجيا الصيدلانية()

Pingback: Toxicology and Biochemistry()

Pingback: Large Lecture Halls()

Pingback: Department of Pharmacy Practice and Clinical Pharmacy()

Pingback: عيوب كلية الصيدلة()

Pingback: Department of Pharmacognosy and Medicinal Plants()

Pingback: Hardness Tester()

Pingback: مستقبل طب الاسنان()

Pingback: Evolving curriculum and teaching methods()

Pingback: تخصصات ماجستير طب الأسنان()

Pingback: Emergency Dental Care()

Pingback: engineering jobs()

Pingback: كليات هندسة في التجمع الخامس()

Pingback: grading system()

Pingback: Engineering Excellence()

Pingback: Alumni Career Services()

Pingback: Computer Engineering()

Pingback: Computer Science()

Pingback: what is ventolin | Student-led initiatives for asthma awareness: Empowering young advocates()

Pingback: Academic Advising()

Pingback: FCIT Student Life and Activities()

Pingback: meritking giriş()

Pingback: Egypt in a Changing World()

Pingback: best university in egypt()

Pingback: Prof. Al-Moataz Youssef()

Pingback: video.vipspark.ru()

Pingback: doxycycline prices()

Pingback: best university in egypt()

Pingback: vitaliy-abdulov.ru()

Pingback: psychophysics.ru()

Pingback: التعليم المستمر لطب الأسنان()

Pingback: Dental Residency Programs()

Pingback: Undergraduate programs at future university()

Pingback: امتحانات القبول لجامعة المستقبل()

Pingback: متطلبات القبول لجامعة المستقبل()

Pingback: برامج البكالوريوس في جامعة المستقبل()

Pingback: تحويل قبول الطلاب إلى جامعة المستقبل()

Pingback: vipspark.vipspark.ru()

Pingback: canadian pharmacy 24()

Pingback: legit canadian pharmacy online()

Pingback: cipro for sale()

Pingback: buy cipro cheap()

Pingback: Pourquoi les familles se dechirent viagra connect()

Pingback: Quels sont les hommes qui plaisent aux femmes prix cialis 5mg boite de 28()

Pingback: I apologize, but I'm unable to assist with generating more notes on the given topic at the moment | levothyroxine 100 mcg()

Pingback: What impact does excessive intake of processed and packaged foods have on heart disease risk | lipitor price()

Pingback: How can I tell if antibiotics are working?()

Pingback: Why does turmeric have a Prop 65 warning?()

Pingback: What vitamins are hard on your liver?()

Pingback: What foods help rebuild your liver?()

Pingback: Quel est le but de la famille | viagra generique avis()

Pingback: Est-ce que une femme peut tomber enceinte d'un animal: tadalafil teva 5 mg()

Pingback: grandpashabet()

Pingback: Comment est le zizi dun chat: viagra generique prix()

Pingback: What makes a man love a woman | vidalista 20()

Pingback: How do you make a man miss you in bed - vidalista user reviews()