By traditional measure my first professional mentor was a failure. Make no mistake, he was a good man and a good leader, and over four years of grueling work I watched him take our failing organization and turn it into a disciplined project management run shop. He poured his heart and soul into that group, but when he left for another job our organization crumbled, reverting to the same pattern of failure it had before he had arrived. And this failure left me confused. He was a profoundly influential person to me, and what did this failure say about him and his leadership? Had he failed as a leader? Had everything I learned from him been suspect, or even wrong? What legacy had he left behind?

My story isn’t unique. Throughout their careers, most people will serve as both leaders and followers in some capacity. As such, they will both create and watch similar situations. They will leave organizations and watch their efforts dissolve. They will, like me, watch their boss’ hard work come to naught. What does this say about the success of their leadership? What does it say about their legacy? The questions have driven me to explore the concept of legacy, and how it leaders can ensure that the legacy they leave is a positive one.

I have been grappling with these questions, but I did not know them as “legacy.” I didn’t know what “legacy” was. I am not sure I can completely define it today. But after lengthy exploration, I am closer to understanding it, and that’s what this is about, the weird path I took and the connections I have made to answer these questions.

This journey started with an obsession. For the last year and a half I have been researching the Battle of Britain, a seminal aerial battle of World War II. I found deep lessons on leadership in the history of that conflict, and began to see the beginning of an answer to my questions about legacy.

I don’t intend for this to be a detailed history lesson. But you’ll need to understand a few things for context, so let me give you a brief synopsis.

The Battle of Britain

In September 1939 the Germans invaded Poland. Two days later, Britain and France declared war on Nazi Germany but for about six months not much happened. The combatants watched each other warily across the English Channel, but did neither took the offensive. The chattering classes jeered and called it the “Phoney War” or the “Bore War.”

In April of 1940 the Germans struck, invading Norway and Denmark. In May they turned their blitzkrieg against the British and French forces in France. The Allies were caught by surprise and within weeks they fell back in retreat. In the opening days of June, the British Army found itself surrounded at the French port of Dunkirk, with their backs to the sea.

British military leaders predicted a grave disaster, yet against all odds More than 300,000 men of that army were miraculously saved, pulled from the beach by the Royal Navy and British citizens in any vessel that could float. But it was no victory. The British Army had run for their lives, leaving all their weapons and equipment on the beaches of France.

When the French surrendered several weeks later, the British were alone and disarmed. By any reasonable standard the war was over. Hitler and his allies were the masters of Continental Europe. Britain stood alone.

With the army in disarray, only the Royal Air Force’s Fighter Command, led by Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding, and his second in command Air Vice Marshal Keith Park, stood between Britain and the expected Nazi invasion. They led the squadrons of young, carefree pilots, like Pilot Officer Albert Ball, who Churchill would later immortalize as “The Few.”

These boys flew planes like the Hawker Hurricane and the legendary Supermarine Spitfire.

As the Germans hurled the might of their air force against English shores, the RAF struggled to survive and stop German bombers intent on breaking Britain’s will.

It seemed an impossible task. The world thought they would lose. They were tragically, comically outnumbered. Germans planes outnumbered them 4.5 to 1 and German pilots were battle hardened veterans. Royal Air Force pilots were barely out of school.

In the long, hot, deadly summer months of 1940 something astounding happened. The Royal Air Force held on.

In the face of overwhelming odds they held their ground and as the summer slogged on they begin to grow stronger. By October, they had beaten off the Nazi hordes and Hitler, his air force demoralized and the RAF Holding firm, called off the invasion of England. He turned his treacherous gaze instead to the east and invaded Russia, where he would break the back of his armies. Britain, and ultimately the free world, were saved.

How did the RAF win? How were they able to beat back the overwhelming hordes of the Luftwaffe? Was it superior people? No. The RAF pilots were less experienced and inadequately trained compared to their foes. At the height of the battle, pilots were reaching the squadrons with less than fifteen hours of instruction, and the results were tragic. Was it better planes? No. Even the famous Spitfire was just barely good enough, and in many ways inferior against the German machines.

No, they won because of superior leadership. Leadership from men like Dowding and Park. I want to focus on Park specifically here because it is his story that started answering my questions about “legacy.”

The Leadership of Air Vice Marshal Keith Park

Keith Park was the number two of Fighter Command, responsible for managing the daily operations of the squadrons Fighting Germany over Southern England. As German raiders crossed the English Channel, he decided which squadrons to send to stop them. Send too many planes up and his forces could be decimated. Send too few and the Germans would make it through. Raids showed up on British radar, but it was often unclear if incoming planes were a feint intended to draw out his forces or a real bombing run. Every day for four months he played a chess match with grave consequences.

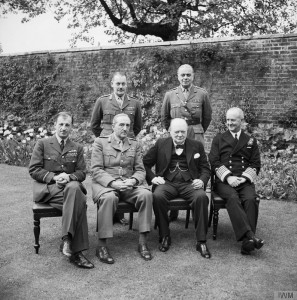

Air Vice Marshall Sir Keith Park. He was the Commander of 11 Group during the battle. © IWM (CM 5631)

Here he is sitting behind the desk at his headquarters outside London. It is a rather standard picture of a military commander. But the truly interesting thing about Keith Park is that this is not how the men and women under his command would recognize him.

This is how they knew him, in a Sidcott flying suit and Mae West life vest, wearing a leather flying helmet and goggles. During the summer months, after he finished his duties at headquarters, he would put on his flying gear, climb into OK-1, his personal Hurricane, and fly to his squadron airfields. He’d arrive alone and unannounced, shunning both spectacle and entourage.

Once on the ground he would talk with the pilots, the armourers, the ground crew, the civilians, anyone he could find. He listened to their problems, addressed their concerns, and answered their questions. But he was also able to see for himself how things really were on the front lines, without filter and without bias.

In this pursuit he willingly placed himself in danger despite the consternation from his superiors at the Air Ministry. OK-1 was the last British plane to fly over the evacuated beaches of Dunkirk. It was circling the smoke stained skies over London’s East End when the German bombers launched their Blitz on London. As the long, breathless summer wore on he logged over 60 trips in OK-1. And his people loved him for it.

After the Battle of Britain was over, Park commanded the air defense of Egypt and then Malta, where he broke the German siege and regained air superiority over the Mediterranean. He was later promoted to Air Chief Marshall and given a command in the Far East. Throughout those commands, he never lost the habit of talking directly to the men and women on the front lines.

Here he is, at the height of his career, sitting cross-legged with his men on the front lines in Burma. I am impressed with this photo. Could you imagine another General, or a CEO doing this? This is obviously not a press meet and greet. There was not a photo op. Look at his shoes. The sole is coming off. Here is a man who leads on his feet.

But that’s just my interpretation, I never met him. What did those who actually served under him think of the man and his leadership? Park’s biographer, Vincent Orange, interviewed people who served under Park, and here are a few of their accounts:

“George Westlake, later a decorated Group Captain, recalled a day in August 1940 when his engine cut dead somewhere over the Isle of Wight amid a great many aircraft, British and German. He promptly spun down to about 10,000 feet and since no one had followed him, he decided to attempt a landing at Westhampnett. Everything went so well that he reckoned he could even land wheels down. Unfortunately, ‘a bloody great line of poplar trees appeared at the last moment, causing him to wreck his Hurricane though he himself escaped unhurt. He was ordered to report to Park at Uxbridge next morning. After he had told his story, Park asked him how many aircraft he had shot down. ‘One, Sir,’ Westlake proudly announced. ‘Pity,’ replied Park. ‘Now your score is exactly zero, isn’t it?’ He then quietly took Westlake to pieces – for not bailing out, for trying to land wheels down without engine power, for hitting the poplars and, in short, for being an idiot. Finally, he told him not to rush back to Tangmere. Westlake, thinking he had been grounded, almost collapsed.

‘No,’ said Park, ‘take the morning off and read the papers in the Mess. I’ll be in at lunch-time and you can buy me a beer.’ “I not only bought him a beer,” Westlake recalled, “he bought me a few, then he asked me to join him for lunch and to this day I simply cannot remember who else was there. As far as I was concerned, I could only see the great Keith Park – what a man. From that day on, I worshipped him.”

Here is another account of Park:

“In January 1942 Park sailed aboard the ship The Viceroy of India and a young New Zealand pilot, John Mason, travelled on the same ship and recalled an occasion when a Major ordered him and some other pilots to leave the boat-deck, where they had been sunning themselves, because that deck was reserved for senior officers. When Park was informed, he at once told all the senior officers that, ‘these young gentleman have faced and will face dangers that none of you will ever meet. They will share any facilities on board this ship equally with you.’ Needless to say, added Mason, this arrangement lasted only until Park disembarked.”

Later in the war, Park was placed in command of the air defense of the island of Malta. Malta was suffering under German bombardment, which Park ultimately stopped. This story is recounted from his time there.

“Park was the first Vice-Marshal anyone had seen doing his rounds on a bicycle. He would arrive at an aerodrome by other transport and then, because of the desperate petrol shortage, pedal his way from squadron to squadron. Soon, however, he obtained a small MG sports car, painted bright red. The sight of Park threading his way through cratered streets in his ‘fire engine’, as it was popularly known, lifted morale everywhere in the island. He enjoyed driving it and he always picked up walking servicemen if he had a spare seat. Lieutenant Commander E.W. Whitley, a squadron mechanic, recalled one such lift, but not what they talked about: ‘From my position, he was almost God!’ Whitley admired the way Park got about on his own, ‘without a tribe of staff officers following, seeing for himself what was going on.’”

These accounts paint a more complete picture of the man, from the people who knew him personally. But what do these stories about an obscure RAF officer have to do with the concept of “legacy?” I’ll share my thought processes through a quick exercise. If I asked you to describe Keith Park, what would you say?

Here are the adjectives I’d use:

- Courageous

- Selfless

- Humble

- Generous

- Direct

- Fair

- Merciful

Those adjectives describe who Park was. But I haven’t really detailed his accomplishments; the things that Park did. I won’t go into great detail, but here is a short list:

- Shot down 22 enemy fighters in World War I

- Led the air defense over Dunkirk

- Led the RAF to victory during the Battle of Britain

- Broke the aerial siege of Malta

That’s a pretty solid record of achievement. His leadership in the Battle of Britain alone would be enough for most people. Park literally saved the free world. As a leader, Park’s accomplishments speak for themselves.

So imagine my shock when, during my research, I came across a story about a statue to Park that was recently unveiled in London. When I saw a picture of the statue I was dumbstruck. In a moment, that picture answered the years of nagging doubt I’d been having about legacy. Since that moment, it has become one of my favorite statues.

That’s a statue to the man, not the Air Vice Marshal. It captures his leadership, not his accomplishments. Here he is, in his Mae West and helmet, pulling on his gloves. Resolute, calm, determined. His statue states simply, “let’s get to work.” Whoever designed the statue knew the sort of person Park was. It blew my mind. I was not used to looking at statues that way.

Here, Park was immortalized for who he was, not what he accomplished. But is that true of all leaders? Is it that simple, that we are remembered more for who we are than what we accomplish? If that’s the case, it should have a profound impact on how leaders approach their legacy.

Not content with a data point of one, I started looking at the statues of other leaders from the Battle of Britain, curious to see what their statues would tell me.

Sir Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Churchill

Let’s start with Winston Churchill, arguably one of the greatest leaders of the 20th Century. More a force of nature than a man, he overcame a childhood of parental neglect and early political missteps to become the embodiment of his country’s defiant stand against Nazi Germany. He was a bombastic, uncomfortable cauldron of ego and inspiration, selfishness and sentiment, strength and softness. But these qualities and his complete abandonment to them made him the galvanizing leader who rallied his country during World War II. But that is how I see him from my research. What did those people who knew him think of the man?

There are too many stories about Churchill that could be told. Too many facets of his personality that could be explored, so I’ll focus on a few anecdotes from his leadership during the Battle of Britain and the Blitz. One such anecdote is from General Hastings Ismay, Churchill’s long beleaguered chief military assistant:

“There was a terrific blitz going on upstairs. The whole of Carlton House Terrace was in flames, and the bombs were dropping all around. Churchill came up smoking his cigar and put on his tin hat. In front of the door of the underground offices was a concrete screen, and everybody tried to prevent him walking out because there was so much metal flying about but he went out and I can see him today with his hands on his stick, smoking his cigar. ‘My God,’ he said, ‘we’ll get the buggers for this.’”

William Manchester, a biographer, describes Churchill in the aftermath of a German attack on London:

“Bundled in a heavy topcoat, his odd little homburg pulled down low, he hurtled through the city streets in an armored car. As soon as it delivered him to a scene of destruction, out he’d take off on foot. He might poke at the edge of bomb craters with his walking stick, or scramble up a pile of rubble to get a better view of the damage. He left his aides, literally, in the dust. With a careless slouch and his shoulders hunched, he charged down the streets, through puddles and over fallen bricks. Always, he sought out the people. He possessed a great gift for making them forget discomfort, danger, and loss and remember they were living history.”

Manchester also recalls a conversation with John Martin, about an event that occurred at the height of the Blitz, when the British were being pummeled by nightly German bombing:

“Churchill, intensely vulnerable to sentiment, witnessed many scenes which caused him to succumb. While driving to Chequers (his country estate) one day, he glimpsed a line of people. Motioning the driver to stop, he asked his detective to enquire what they were queuing for. Told that they hoped to buy birdseed, Churchill’s private secretary John Martin noted: ‘Winston wept.'”

Based on what you know and what those stories have told you, describe Churchill. Take a few minutes and write down a few words. Here are the words I used:

- Defiant

- Stubborn

- Inspiring

- Intelligent

- Sentimental

- Kind

Those adjectives describe Churchill’s personality, but what did he accomplish? Churchill is best known for his leadership as Prime Minister during World War II. He rallied the British people in their darkest hour, when they faced Nazi Germany alone. Like Keith Park, that is accomplishment enough. But he was a prolific man of many talents. Just a few of his many accomplishments are listed below:

- Served in the last cavalry charge of the British Army in Sudan

- Captured by the enemy in the Boer war and escaped

- Served as First Lord of the Admiralty during the World War I

- Served as a Battalion Commander in the trenches during World War I

- Prime Minister of Great Britain who led the country to victory in World War II

- Forged the “special relationship” with the United States

- First person to be named an Honorary Citizen of the United States

- Time Man of the Year 1940, Man of the Half Century 1949

- Published 43 books

- Won the Pulitzer Prize for Literature in 1953

- Painted over 500 paintings as an accomplished artist

So what does the statue of Winston Churchill looks like? Here is the most famous one, in Parliament Square, London.

“Winston Churchill statue, Parliament Square, London” by Eluveitie. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

What does that statue say about how he is remembered? I see his stubbornness and defiance. It is a bronze representation of his storming through London while the streets are ablaze. But I also think the statue is even more powerful from behind.

Churchill 4887775918 by http://www.cgpgrey.com. Licensed under CC BY 2.0

From behind the statue is stooped and hunched; struggling under a great weight. The statue’s combination of defiance and burden, strength and weakness is simply fantastic. It captures the contradiction of personality that defined Churchill. I cannot think of a better symbol of his leadership. Is this a statue of an accomplished Prime Minister? A monument to a Pulitzer Prize winner and Man of the Half Century? Or is it the man himself captured in bronze?

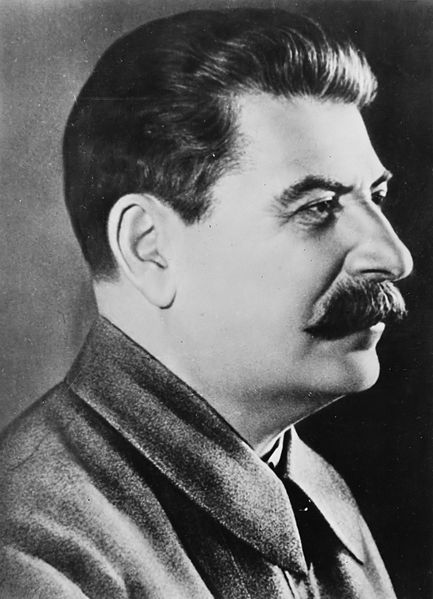

Joseph Stalin

As the leader of the USSR during WWII, Stalin did not directly participate in the Battle of Britain. It would however, be difficult to overestimate the impact he had on the course of the war. In the late 1930’s he led the Great Purge, exiling or executing millions of “dissidents” in the government and armed forces. He also entered into a secret pact with Hitler to divide and occupy Eastern Europe with the Nazis. These actions came to a fateful head in 1941 when Hitler double-crossed Stalin and invaded the Soviet Union. Facing a decimated and demoralized Red Army, the Nazi invasion rolled across the Russian steppes to the suburbs of Moscow. Stalin rallied his industry and armed forces to counter the German threat, mobilizing 34 million men into a revitalized Red Army that ultimately crushed Nazi Germany.

But his dictatorship was a dark and twisted chapter in Russian history that has left a confusing legacy in its wake. Even casual students of history have heard of his darker side, but here is an observation from no less a close colleague than the father of Communism, Vladimir Lenin:

“Stalin is excessively rude, and this defect, which can be freely tolerated in our midstand in contacts among U.S. Communists, becomes a defect which cannot be toleratedin one holding the position of Secretary-General. Because of this, I propose that the comrades consider the method by which Stalin would be removed from this position and by which another man would be selected for it; a man, who above all, would differ from Stalin, in only one quality, namely, greater tolerance, greater loyalty, greater kindness, and more considerate attitude toward the comrades, a less capricious temper, etc.”

Simon Montefiore, a writer for the Daily Mail, recounts a story told to him by Maya Kavtaradze. She was a child in Soviet Russia during Stalin’s reign. Her father Sergo had been a close friend of Stalin during the Russian Revolution, but during the power struggles between Stalin and Trosky, Sergo had backed Trotsky. When Stalin prevailed and came to power, Sergo and his wife were imprisoned and sentenced to be executed. Their daughter Maya wrote Stalin a letter pleading their innocence. For some reason it worked and Stalin had his old friend and his wife released and reunited with their daughter.

One night, not long after, Maya recalls that there was a knock at the door. When Sergo’s wife answered she found her husband standing there meekly. Beside him was Stalin and Beria, Stalin’s notorious head of Secret Police, who was also their personal torturer during their years of imprisonment. Sergo nervously announced that the family was having “guests” for dinner. The night quickly grew ominous, as Simon records. In the middle of small talk, Stalin stopped and asked suddenly:

‘Where’s Maya? I admired her letter.’Her parents were chilled. ‘It was best to keep children out of any politics and away from Stalin,’ Maya told me. But the tyrant insisted. Sophia went to Maya’s room and said: ‘Stalin is here and he wants to meet you.”

‘I don’t want to,’ whispered Maya. ‘I hate him for what he did to you and Papa.

”Say nothing of that,’ hissed Sophia. ‘You must meet him.’

Maya dressed and came out. ‘When I saw him there it was like a poster brought to life,’ she recalled.Stalin greeted her warmly. ‘

Thank you for your letter,’ he said, asking her to sit on his knee. ‘Do you spoil her?’ he asked her parents. ‘I hope you do.’

He questioned Maya about her life when her parents were in jail. Sergo and Sophia tensed – one whisper of complaint could have doomed them all – but Maya, then aged 11, answered him carefully.’My poor parents dreaded what I might say to him,’ she said. ‘He was so kind, so gentle – he kissed me on the cheek and I looked into his honey-coloured, gleaming eyes, but I was so anxious.’

Then Stalin turned to Sophia: ‘We tortured you too much,’ he said.”

Same exercise again. How would you describe Stalin as a man? Here is my list:

- Egomanical

- Treacherous

- Arrogant

- Duplicitous

- Sinister

- Capricious

- Demanding

- Overbearing

- Unstable

But Stalin was more than a mad tyrant. He had an impressive record of achievement. Here are some of his most lasting accomplishments:

- Rapidly industrialized the feudal Russian society through his 5 year plans

- Mobilized the transport of Russian industry beyond the Ural Mountains after the Nazi invasion

- Mobilized and equipped the Red Army and crushed the Third Reich

- Turned the USSR into the world’s second nuclear power

So what would Stalin’s statue look like? Not surprisingly, it is hard to find statues to Stalin that are still standing, but here is a photo of the statue that was raised in Budapest as a “gift” to Hungary on Stalin’s 70th birthday.

What does this statue say about Stalin? Like most Soviet statues, its huge, larger than life, imposing. A testament to Stalin’s arrogance and ego. A fitting tribute to his need to dominate and overpower his countrymen. Interestingly, Stalin was only 5’4″ in real life.

But the truly interesting thing is that the people of Hungary tore this statue down five years later. And they didn’t just tear it down, they demolished it and left behind only the statue’s boots. What remains today is what may be my second favorite statue.

That monument says it all. Despite all of his accomplishments, he was so reviled by the people who lived under him that they tore his statue down. And they won’t let him be forgotten to history either. They left his empty boots as a reminder of their contempt. What does that say about leaders who try to write their own legacy?

So What is Legacy?

Even after exploring the topic for a few years I’m not sure I have a complete definition. But I can say that legacy, at its most basic, is how a leader is remembered after they are gone. It’s their echo. But I am convinced, that who that person is becomes more important to defining that legacy than what they accomplish.

Legacy is the sum of the stories people tell, and history has taught me that they tell stories about the person, not the deed. This may seem obvious, but we still talk of legacy as the sum of accomplishments. Near the end of their last term, every US president makes a push for some agreement, some deal, some problem solved to cement his legacy. Nearing retirement, CEO’s look for a deal, a product, a sales number to ensure their legacy. Leaders all yearn for the lasting achievement, the tangible thing, the glory to live on after they are gone, but the simple fact remains that they have already built their legacy long before they left. By their behavior, their daily interactions, by the kind of person they were while they strove for those lofty accomplishments.

The truth is that very few leaders will ever have a statue built. But they would be better leaders in their lives and their business pursuits if they conducted themselves as if they would. Perhaps they should pause and ask themselves, ‘what do I want my statue to say?’

Pingback: Viagra vs cialis vs levitra()

Pingback: Buy cialis()

Pingback: Cialis uk()

Pingback: Viagra kaufen()

Pingback: Cialis tablets()

Pingback: Viagra vs cialis()

Pingback: Cialis great britain()

Pingback: Generic for viagra()

Pingback: Viagra vs cialis vs levitra()

Pingback: Cialis 5 mg()

Pingback: Cialis 5 mg()

Pingback: Cialis 5 mg()

Pingback: essayforme()

Pingback: Cialis prices()

Pingback: Cialis 5 mg()

Pingback: latestvideo sirius192 abdu23na7082 abdu23na88()

Pingback: freshamateurs359 abdu23na2547 abdu23na3()

Pingback: tubela.net195 afeu23na9813 abdu23na45()

Pingback: newtube tube planet556 afeu23na2091 abdu23na73()

Pingback: tubepla.net download339 afeu23na2571 abdu23na32()

Pingback: 803moClW3ga()

Pingback: hdmobilesex.me()

Pingback: online prescription for cialis()

Pingback: Cialis generic()

Pingback: get cialis prescription online()

Pingback: buy cialis without a doctor's()

Pingback: canadian drug()

Pingback: Viagra 5 mg()

Pingback: Buy viagra()

Pingback: Cialis generic()

Pingback: Buy generic viagra()

Pingback: levitra generic alternative()

Pingback: canada levitra()

Pingback: Low cost viagra 20mg()

Pingback: cheap 20mg levitra()

Pingback: viagra pills()

Pingback: viagra without doctor prescription()

Pingback: online viagra()

Pingback: viagra 100mg()

Pingback: canadian pharmacies online()

Pingback: canadian pharmacies online()

Pingback: drugstore online()

Pingback: canada pharmacy()

Pingback: international pharmacy()

Pingback: tadalafil()

Pingback: cialis 20mg()

Pingback: cialis prices()

Pingback: canadian pharmacies online()

Pingback: buy viagra online()

Pingback: hs;br()

Pingback: tureckie_serialy_na_russkom_jazyke()

Pingback: tureckie_serialy()

Pingback: 00-tv.com()

Pingback: +1+()

Pingback: æóêè+2+ñåðèÿ()

Pingback: Ñìîòðåòü ñåðèàëû îíëàéí âñå ñåðèè ïîäðÿä()

Pingback: Ñìîòðåòü âñå ñåðèè ïîäðÿä()

Pingback: watch()

Pingback: ++++++()

Pingback: HD-720()

Pingback: guardians+of+the+galaxy+2()

Pingback: strong woman do bong soon()

Pingback: my id is gangnam beauty()

Pingback: 2020()

Pingback: kpop+star+season+6+ep+9()

Pingback: Video()

Pingback: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10()

Pingback: wwin-tv.com()

Pingback: amoxicillin()

Pingback: Watch TV Shows()

Pingback: Kinokrad 2019 Kinokrad Hd()

Pingback: Kinokrad()

Pingback: filmy-kinokrad()

Pingback: kinokrad-2019()

Pingback: filmy-2019-kinokrad()

Pingback: serial()

Pingback: cerialest.ru()

Pingback: youtube2019.ru()

Pingback: dorama hdrezka()

Pingback: movies hdrezka()

Pingback: HDrezka()

Pingback: kinosmotretonline()

Pingback: LostFilm HD 720()

Pingback: trustedmdstorefy.com()

Pingback: bofilm ñåðèàë()

Pingback: bofilm()

Pingback: 1 seriya()

Pingback: Êîíñóëüòàöèÿ ïñèõîëîãà()

Pingback: topedstoreusa.com()

Pingback: hqcialismht.com()

Pingback: viagramdtrustser.com()

Pingback: купить виагру ли()

Pingback: lindamedic.com()

Pingback: гдз по русскому языку тростенцова()

Pingback: canadianpharmacystorm.com()

Pingback: gencialiscoupon.com()

Pingback: гдз по геометрии 9()

Pingback: genericvgrmax.com()

Pingback: гдз по физике 9 класс()

Pingback: гдз 10 11 по алгебре()

Pingback: гдз по химии()

Pingback: гдз по алгебре 8 макарычев()

Pingback: гдз по немецкому()

Pingback: viagrawithoutdoctorspres.com()

Pingback: гдз 5 класс()

Pingback: гдз по русскому языку класс()

Pingback: canpharmb3.com()

Pingback: гдз тетрадь()

Pingback: гдз 4 класс()

Pingback: 4serial.com()

Pingback: See-Season-1()

Pingback: Evil-Season-1()

Pingback: Evil-Season-2()

Pingback: Evil-Season-3()

Pingback: Evil-Season-4()

Pingback: Dollface-Season-1()

Pingback: Queer-Eye-We-re-in-Japan-Season-1()

Pingback: гдз макарычев 7 класс()

Pingback: гдз по геометрии 9 атанасян()

Pingback: гдз()

Pingback: ciapwronline.com()

Pingback: serial 2020()

Pingback: Dailymotion()

Pingback: Watch+movies+2020()

Pingback: serial-video-film-online()

Pingback: tvrv.ru()

Pingback: 1plus1serial.site()

Pingback: #1plus1()

Pingback: 1plus1()

Pingback: Watch Movies Online()

Pingback: Film()

Pingback: Film 2020()

Pingback: Film 2021()

Pingback: Top 10 Best()

Pingback: watch online TV LIVE()

Pingback: human design()

Pingback: dizajn cheloveka()

Pingback: viagra()

Pingback: viagra online()

Pingback: cherkassy film()

Pingback: ¯jak Son³k 2020()

Pingback: generic cialis()

Pingback: cialis 20mg()

Pingback: generic viagra 100mg()

Pingback: buy viagra online()

Pingback: viagra prescription online()

Pingback: cialis()

Pingback: viagra pills()

Pingback: buy cialis()

Pingback: generic viagra()

Pingback: buy cialis cheap()

Pingback: cialis pills()

Pingback: levitra()

Pingback: film strelcov()

Pingback: t-34()

Pingback: canadian online pharmacies()

Pingback: online pharmacy canada()

Pingback: Cialis price()

Pingback: sildenafil()

Pingback: generic cialis()

Pingback: cialis()

Pingback: viagra()

Pingback: Beograd film 2020 Beograd()

Pingback: viagra online()

Pingback: sildenafil citrate()

Pingback: buy viagra()

Pingback: psiholog online()

Pingback: cialis online()

Pingback: psyhelp_on_line()

Pingback: coronavirus()

Pingback: cialis from india()

Pingback: PSYCHOSOCIAL()

Pingback: rasstanovka hellinger()

Pingback: buy cialis pills()

Pingback: Levitra vs viagra()

Pingback: cialis online()

Pingback: Cherekasi film 2020()

Pingback: generic viagra()

Pingback: aralen chloroquine()

Pingback: cialis 20mg()

Pingback: generic levitra()

Pingback: cialis pill()

Pingback: Buy cheap viagra internet()

Pingback: Viagra 100 mg()

Pingback: film doktor_liza()

Pingback: buy pain meds from mexico()

Pingback: djoker film()

Pingback: bob marley cbd drink()

Pingback: viagra for sale()

Pingback: cbd()

Pingback: coronavirus antiviral drugs()

Pingback: viagra for sale()

Pingback: buy viagra online()

Pingback: cialis over the counter 2020()

Pingback: gidonline-filmix.ru()

Pingback: canadian pharmacy()

Pingback: koronavirus-v-ukraine-doktor-komarovskiy()

Pingback: albuterol inhaler()

Pingback: cheap viagra 100mg free shipping()

Pingback: is there a generic cialis()

Pingback: viagra for women over 50()

Pingback: cialis over counter()

Pingback: cialis savings card()

Pingback: cialis over the counter walmart()

Pingback: viagra online()

Pingback: cialis coupon walmart()

Pingback: buy viagra()

Pingback: cheap kaletra()

Pingback: generic cialis()

Pingback: cheap viagra()

Pingback: tylenol pm generic()

Pingback: discount viagra online()

Pingback: viagra 50mg()

Pingback: how long does viagra last()

Pingback: viagra generic()

Pingback: viagra generic()

Pingback: over the counter viagra()

Pingback: Canadian Pharmacies Online()

Pingback: generic cialis()

Pingback: Canadian Pharcharmy Online()

Pingback: buy cheap cialis()

Pingback: ed medication()

Pingback: best ed medication()

Pingback: generic viagra()

Pingback: cialis generic tadalafil()

Pingback: viagra()

Pingback: how long does cialis last()

Pingback: erection pills()

Pingback: generic cialis tadalafil()

Pingback: 100mg viagra without a doctor prescription()

Pingback: cialis tadalafil 20mg()

Pingback: cvs pharmacy()

Pingback: t.me/psyhell()

Pingback: Ïñèõîëîã îíëàéí()

Pingback: viagra pills()

Pingback: Buy cheap cialis()

Pingback: prescription drugs()

Pingback: bitly.com()

Pingback: viagra 100mg()

Pingback: viagra price()

Pingback: viagra coupon()

Pingback: cheap viagra()

Pingback: cialis generic()

Pingback: cialis coupon()

Pingback: canadian pharmacy cialis()

Pingback: cialis 5mg()

Pingback: viagra pill()

Pingback: online levitra()

Pingback: generic cialis()

Pingback: vardenafil online pharmacy()

Pingback: levitra pill()

Pingback: viagra for sale()

Pingback: virgin casino online nj()

Pingback: doubleu casino online casino()

Pingback: rlowcostmd.com()

Pingback: sildenafil 20()

Pingback: real money casino app()

Pingback: real money casino online usa()

Pingback: viagra overnight()

Pingback: bitly()

Pingback: best generic viagra websites()

Pingback: payday loans()

Pingback: movies-tekstmovies-tekst()

Pingback: payday advance()

Pingback: buy cialis online()

Pingback: no credit check loans()

Pingback: Zemlyane 2005 smotret onlajn()

Pingback: cheap erectile dysfunction pills online()

Pingback: Top Smart Drugs according to Science()

Pingback: Best Vaginal Tightening Gel()

Pingback: viagra for sale()

Pingback: starting an exercise program()

Pingback: dr oz keto supplements()

Pingback: best real money online casinos()

Pingback: health and medical news and information()

Pingback: chewable viagra 100mg()

Pingback: generic for cialis()

Pingback: online casinos australia paypal()

Pingback: doubleu casino online casino()

Pingback: Mybookie()

Pingback: online casino in rhode island()

Pingback: cialis internet()

Pingback: pharmacy()

Pingback: effects of 100 mg viagra()

Pingback: 5 mg cialis()

Pingback: propecia()

Pingback: generic cialis()

Pingback: cbd oil for sale()

Pingback: cialis 20()

Pingback: cbd oil()

Pingback: online casino real money us()

Pingback: smotret onlajn besplatno v kachestve hd 1080()

Pingback: best quality cbd oil for sale()

Pingback: gusmeasu.com()

Pingback: movies-unhinged-film()

Pingback: malenkie-zhenshhiny-2020()

Pingback: dom 2()

Pingback: online casino usa real money()

Pingback: doubleu casino()

Pingback: levitra online()

Pingback: gambling games()

Pingback: zoom-psykholog()

Pingback: zoom-viber-skype()

Pingback: cialis over the counter at walmart()

Pingback: buy ed pills online()

Pingback: generic name for viagra()

Pingback: viagra for sale()

Pingback: viagra for sale()

Pingback: Vratar Galaktiki Film, 2020()

Pingback: cheap viagra()

Pingback: Vratar()

Pingback: Cherkassy 2020()

Pingback: chernobyl-hbo-2019-1-sezon()

Pingback: online viagra()

Pingback: canadian pharmacy king()

Pingback: best ed pills()

Pingback: moskva-psiholog()

Pingback: buy cialis online safely()

Pingback: buy viagra cheap()

Pingback: batmanapollo.ru()

Pingback: generic viagra online()

Pingback: buy viagra on line()

Pingback: buy metformina 1000mg for diabetes()

Pingback: buy viagra online canada()

Pingback: buy cheap prescription drugs online()

Pingback: generic prednisone for sale()

Pingback: 323()

Pingback: 525()

Pingback: plaquenil()

Pingback: dom2-ru()

Pingback: Tenet Online()

Pingback: best place to buy viagra online()

Pingback: cheap cialis()

Pingback: free casino games()

Pingback: buy legit viagra online()

Pingback: low dose viagra daily where to buy()

Pingback: viagra cost()

Pingback: psy psy psy psy()

Pingback: propecia()

Pingback: viagra without a doctor prescription()

Pingback: where can i buy viagra online forum()

Pingback: generic viagra()

Pingback: buy sildenafil()

Pingback: cheap viagra()

Pingback: Viagra 120 mg for sale()

Pingback: krsmi.ru()

Pingback: where to buy Viagra 200mg()

Pingback: tadalafil pills()

Pingback: buy sildenafil generic()

Pingback: cialis tadalafil()

Pingback: how to buy Viagra 150 mg()

Pingback: Viagra 25mg for sale()

Pingback: how to purchase Cialis 20 mg()

Pingback: Cialis 80mg price()

Pingback: buying viagra online()

Pingback: cheap Cialis 10mg()

Pingback: viagra generic()

Pingback: Cialis 60mg pharmacy()

Pingback: buy viagra()

Pingback: cheap viagra()

Pingback: Cialis 20 mg without a prescription()

Pingback: cost of Cialis 60mg()

Pingback: like-v.ru()

Pingback: Cialis 10 mg for sale()

Pingback: viagra cheap()

Pingback: Cialis 80 mg pharmacy()

Pingback: sildenafil 120 mg otc()

Pingback: canadian express pharmacy()

Pingback: tadalafil 10mg without prescription()

Pingback: levitra 20 mg no prescription()

Pingback: lasix 100mg tablet()

Pingback: cheap furosemide 100mg()

Pingback: propecia 5 mg australia()

Pingback: lexapro 10mg over the counter()

Pingback: canadian viagra()

Pingback: viagra generic()

Pingback: where to buy abilify 10 mg()

Pingback: ou trouver viagra sans ordonnance()

Pingback: actos 15 mg tablets()

Pingback: aldactone 100 mg pharmacy()

Pingback: CFOSPUK()

Pingback: fgu0ygW()

Pingback: allegra 120 mg online pharmacy()

Pingback: allopurinol 300 mg for sale()

Pingback: where can i buy amaryl 4mg()

Pingback: amoxicillin 500 mg for sale()

Pingback: ampicillin 500 mg prices()

Pingback: antabuse 500 mg otc()

Pingback: antivert 25 mg purchase()

Pingback: where can i buy arava 20 mg()

Pingback: strattera 10mg united states()

Pingback: aricept 10mg no prescription()

Pingback: brand name viagra()

Pingback: cialis coupons()

Pingback: arimidex 1mg usa()

Pingback: buy tadalafil()

Pingback: tamoxifen 20mg generic()

Pingback: ashwagandha 60caps online pharmacy()

Pingback: cialis how long does it last()

Pingback: cheap atarax 25mg()

Pingback: augmentin 250/125 mg nz()

Pingback: prescription drugs online without doctor()

Pingback: avapro 300mg australia()

Pingback: cost of avodart 0,5mg()

Pingback: viagra shqip()

Pingback: baclofen 10 mg usa()

Pingback: bactrim 800/160 mg over the counter()

Pingback: viagra dosage()

Pingback: benicar 20mg pharmacy()

Pingback: buy viagra()

Pingback: how long cialis take to work()

Pingback: Biaxin 500mg canada()

Pingback: Premarin 0,625 mg over the counter()

Pingback: buspar 5mg tablet()

Pingback: cialis tubs()

Pingback: viagra without a doctor prescription from canada()

Pingback: CBD Coupons and Deals()

Pingback: cardizem for sale()

Pingback: akmeologiya()

Pingback: dizain cheloveka()

Pingback: human-design-hd()

Pingback: buy viagra new york()

Pingback: buy cialis online()

Pingback: casodex usa()

Pingback: cialis for sale()

Pingback: catapres 100mcg prices()

Pingback: buy cheap viagra()

Pingback: ceclor 250mg pharmacy()

Pingback: cheapest ceftin()

Pingback: celebrex uk()

Pingback: male ed()

Pingback: how to buy celexa()

Pingback: https://apnews.com/press-release/newmediawire/lifestyle-diet-and-exercise-exercise-2d988b50b0b680bee24da8e46047df20()

Pingback: cephalexin 500mg pills()

Pingback: buy viagra online canada pharmacy()

Pingback: cost of cipro 500mg()

Pingback: generic viagra online()

Pingback: where to buy claritin 10 mg()

Pingback: slots real money()

Pingback: online casino usa real money()

Pingback: casino slots()

Pingback: doubleu casino()

Pingback: real casino online()

Pingback: real casinos online no deposit()

Pingback: cheap ed pills()

Pingback: chumba casino()

Pingback: free slots online()

Pingback: virgin casino online nj login()

Pingback: slots real money()

Pingback: car insurance quotes online()

Pingback: car insurance quotes rates florida()

Pingback: progressive insurance quote()

Pingback: buy cialis()

Pingback: viagra nitrates()

Pingback: low price car insurance quotes()

Pingback: access car insurance()

Pingback: auto liability insurance()

Pingback: car insurance quotes companies in texas()

Pingback: batmanapollo()

Pingback: autoowners insurance()

Pingback: prescription drugs without prior prescription()

Pingback: general insurance quote()

Pingback: car insurance quotes online()

Pingback: canada ed drugs()

Pingback: personal loans with bad credit()

Pingback: best place to buy viagra online forum()

Pingback: payday loans()

Pingback: viagra for young adults()

Pingback: payday loans utah()

Pingback: installment loans in ga()

Pingback: quick loans loan()

Pingback: tsoy()

Pingback: bad credit loans lancaster ca()

Pingback: flomax español()

Pingback: amoxicillin online purchase()

Pingback: best payday loans()

Pingback: advance personal loans()

Pingback: buddy group cbd oil mod()

Pingback: cbd oil mg dosage for anxiety()

Pingback: viagra pill where to buy()

Pingback: hemp oil vs cbd oil for pain()

Pingback: price viagra 100mg()

Pingback: cbd oil for chronic pain()

Pingback: healthy man viagra()

Pingback: instant online payday loans()

Pingback: medical cannabis oil for sale high cbd rso()

Pingback: generic viagra from mexico()

Pingback: difference between hemp oil and cbd oil()

Pingback: buy sildenafil online usa()

Pingback: are cbd gummies a scam()

Pingback: 44548()

Pingback: 44549()

Pingback: cbd cannabis()

Pingback: hod-korolevy-2020()

Pingback: cbd oil for cancer patients chocolate()

Pingback: 25 mg viagra price()

Pingback: Buy cheap viagra internet()

Pingback: write my papers()

Pingback: viagra online oversea()

Pingback: assignment of leases()

Pingback: discovery ed assignments()

Pingback: admission essay writing service()

Pingback: define assignments()

Pingback: price generic viagra()

Pingback: university essay writing service()

Pingback: HD()

Pingback: what is the best essay writing service()

Pingback: how to write argument essay()

Pingback: writing essay online()

Pingback: best online essay writing service()

Pingback: how to get viagra online in usa()

Pingback: cleocin usa()

Pingback: Buy viagra now online()

Pingback: clomid nz()

Pingback: 158444()

Pingback: Testosterone Supplements()

Pingback: cheap clonidine 0,1 mg()

Pingback: clozaril pills()

Pingback: groznyy-serial-2020()

Pingback: Us discount viagra overnight delivery()

Pingback: colchicine for sale()

Pingback: where to buy symbicort inhaler 160/4,5 mcg()

Pingback: generic cialis tadalafil()

Pingback: where can i buy combivent 50/20 mcg()

Pingback: coreg 25mg cost()

Pingback: cialis online()

Pingback: 38QvPmk()

Pingback: bitly.com/doctor-strange-hd()

Pingback: bitly.com/eternals-online()

Pingback: compazine 5 mg nz()

Pingback: bitly.com/maior-grom()

Pingback: matrica-film()

Pingback: dzhonuikfilm4()

Pingback: bitly.com/batman20212022()

Pingback: order coumadin 1 mg()

Pingback: bitly.com/venom-2-smotret-onlajn()

Pingback: bitly.com/nevremyaumirat()

Pingback: bitly.com/kingsmankingsman()

Pingback: bitly.com/3zaklyatie3()

Pingback: bitly.com/1dreykfilm()

Pingback: bitly.com/topgunmavericktopgun()

Pingback: bitly.com/flash2022()

Pingback: bitly.com/fantasticheskietvari3()

Pingback: bitly.com/wonderwoman1984hd()

Pingback: research paper writing service reviews()

Pingback: cozaar 100 mg generic()

Pingback: viagra junk email()

Pingback: Buy discount viagra()

Pingback: dissertation for phd()

Pingback: crestor 20mg coupon()

Pingback: college essay community service()

Pingback: viagra()

Pingback: where can i buy cymbalta 30 mg()

Pingback: Canadian healthcare viagra()

Pingback: dapsone 1000caps united kingdom()

Pingback: ddavp 0.1 mg cost()

Pingback: depakote purchase()

Pingback: cheapest diamox 250 mg()

Pingback: differin without prescription()

Pingback: diltiazem 60mg generic()

Pingback: cheap viagra()

Pingback: doxycycline 100 mg united kingdom()

Pingback: dramamine 50mg pharmacy()

Pingback: elavil no prescription()

Pingback: canadian online pharmacy()

Pingback: 1444()

Pingback: erythromycin without a prescription()

Pingback: buy Nolvadex online()

Pingback: etodolac for sale()

Pingback: flomax 0,2 mg uk()

Pingback: flonase nasal spray 50 mcg without a doctor prescription()

Pingback: garcinia cambogia 100caps over the counter()

Pingback: buying pills online()

Pingback: geodon 80mg prices()

Pingback: hyzaar over the counter()

Pingback: how long does cialis take to work()

Pingback: imdur pills()

Pingback: cialis generic()

Pingback: tadalafil cheap()

Pingback: cialis price()

Pingback: where can i buy imitrex 25 mg()

Pingback: imodium 2 mg prices()

Pingback: viagra walgreens()

Pingback: viagra pills()

Pingback: check out this site()

Pingback: viagra online canada pharmacy()

Pingback: generic viagra cost()

Pingback: imuran 50mg without a doctor prescription()

Pingback: can women take viagra()

Pingback: natural viagra for men()

Pingback: zithromax pill()

Pingback: where can i buy indocin()

Pingback: lamisil usa()

Pingback: viagra generic for sale()

Pingback: levaquin 500 mg pharmacy()

Pingback: generic viagra()

Pingback: lopid tablet()

Pingback: lopressor 50mg purchase()

Pingback: luvox without a prescription()

Pingback: macrobid uk()

Pingback: buy meclizine()

Pingback: buy brand viagra online()

Pingback: over the counter erectile dysfunction pills()

Pingback: how to buy mestinon()

Pingback: Medex()

Pingback: generic Zovirax()

Pingback: micardis uk()

Pingback: cleantalkorg2.ru()

Pingback: 232dfsad()

Pingback: best canadian pharmacy()

Pingback: mobic united states()

Pingback: canadian pharmacies shipping to usa()

Pingback: motrin uk()

Pingback: Sporanox()

Pingback: cheap nortriptyline()

Pingback: periactin no prescription()

Pingback: canadian pharmacies shipping to usa()

Pingback: phenergan 25mg pills()

Pingback: plaquenil otc()

Pingback: prednisolone 40mg generic()

Pingback: prevacid 30mg without a doctor prescription()

Pingback: cheap viagra()

Pingback: proair inhaler 100 mcg for sale()

Pingback: cleantalkorg2.ru/sitemap.xml()

Pingback: cheap procardia()

Pingback: proscar 5 mg online()

Pingback: protonix 20mg without a doctor prescription()

Pingback: cheap viagra()

Pingback: provigil nz()

Pingback: viagra online indian pharmacy()

Pingback: buy pulmicort 100 mcg()

Pingback: amoxicillin 500 mg without a prescription()

Pingback: pyridium united states()

Pingback: join vk()

Pingback: reglan united states()

Pingback: vk login()

Pingback: buy zithromax online()

Pingback: remeron 30mg generic()

Pingback: benadryl gel caps()

Pingback: retin-a cream 0.05% pills()

Pingback: allegra 300()

Pingback: revatio online()

Pingback: risperdal 2mg tablets()

Pingback: where can i buy robaxin 500 mg()

Pingback: buy rogaine 5%()

Pingback: cheapest seroquel 100 mg()

Pingback: singulair tablet()

Pingback: cheapest skelaxin 400 mg()

Pingback: viagra online usa()

Pingback: spiriva united states()

Pingback: order tenormin()

Pingback: where can i buy thorazine()

Pingback: toprol 25mg united kingdom()

Pingback: cheap tricor()

Pingback: buy generic viagra()

Pingback: how to buy valtrex()

Pingback: order verapamil()

Pingback: voltaren 100mg over the counter()

Pingback: wellbutrin 150mg usa()

Pingback: zanaflex pharmacy()

Pingback: uses for cialis()

Pingback: zestril tablets()

Pingback: explanation()

Pingback: zithromax tablets()

Pingback: cost of zocor()

Pingback: zovirax 200mg over the counter()

Pingback: zyloprim 300 mg online()

Pingback: order zyprexa 5mg()

Pingback: brand viagra uk()

Pingback: zyvox 600mg coupon()

Pingback: cheapest sildenafil()

Pingback: xylocaine()

Pingback: tadalafil generic()

Pingback: furosemide pills()

Pingback: buy amoxicillin online with paypal()

Pingback: how to purchase escitalopram 20mg()

Pingback: aripiprazole without a doctor prescription()

Pingback: svaty7sezon()

Pingback: svaty 7 sezon()

Pingback: svaty 7()

Pingback: buy viagra without prescription()

Pingback: pioglitazone 15 mg without prescription()

Pingback: best place to buy generic drugs()

Pingback: spironolactone for sale()

Pingback: tadalafil cost at walmart()

Pingback: fexofenadine 180 mg cheap()

Pingback: glimepiride 2 mg no prescription()

Pingback: walmart pharmacy()

Pingback: meclizine 25mg without prescription()

Pingback: leflunomide 20mg uk()

Pingback: buy viagra online()

Pingback: where to buy anastrozole 1 mg()

Pingback: cost of irbesartan 300 mg()

Pingback: order dutasteride()

Pingback: olmesartan 40mg cost()

Pingback: cheapest buspirone 10mg()

Pingback: clonidine without a doctor prescription()

Pingback: cefuroxime cost()

Pingback: citalopram 20 mg nz()

Pingback: cephalexin otc()

Pingback: tadalafil 20 mg()

Pingback: ciprofloxacin nz()

Pingback: cialis professionals()

Pingback: cialis()

Pingback: loratadine cost()

Pingback: clozapine 100mg cheap()

Pingback: generic viagra for sale()

Pingback: how to buy prochlorperazine()

Pingback: cheapest place to buy generic viagra()

Pingback: carvedilolmg nz()

Pingback: warfarin australia()

Pingback: rosuvastatin without a prescription()

Pingback: how to purchase desmopressinmg()

Pingback: price of cialis at walgreens()

Pingback: divalproex 500 mg united states()

Pingback: trazodone nz()

Pingback: citrate sildenafil()

Pingback: tolterodine pharmacy()

Pingback: acetazolamide canada()

Pingback: fluconazole otc()

Pingback: phenytoin for sale()

Pingback: generic cialis mexico()

Pingback: oxybutynin medication()

Pingback: viagra online asia()

Pingback: how to purchase doxycycline()

Pingback: order bisacodyl 5 mg()

Pingback: order generic viagra()

Pingback: where to buy viagra punta cana dominican()

Pingback: venlafaxine united states()

Pingback: amitriptyline 25 mg online pharmacy()

Pingback: 141genericExare()

Pingback: permethrin without a prescription()

Pingback: cialis()

Pingback: generic viagra cialis()

Pingback: cheap erythromycin()

Pingback: kndxriyl()

Pingback: estradiol no prescription()

Pingback: ed medications()

Pingback: tik tok()

Pingback: etodolac pills()

Pingback: ffmddrmn()

Pingback: ed pills for sale()

Pingback: ed treatment review()

Pingback: how to purchase fluticasone 50 mcg()

Pingback: where can i buy cialis online safely()

Pingback: how to order viagra()

Pingback: sildenafil hoe gebruiken()

Pingback: online doctor prescription for viagra()

Pingback: wat zijn de beste viagra pillen()

Pingback: what is ivermectin for dogs()

Pingback: can you take azithromycin when pregnant()

Pingback: lasix side effects()

Pingback: glipizide usa()

Pingback: buy single viagra pills uk()

Pingback: sumycin online()

Pingback: where to buy hydrochlorothiazide 5 mg()

Pingback: order panmycin online()

Pingback: how to purchase isosorbide 40 mg()

Pingback: buy ampicillin generic()

Pingback: sumatriptan 50mg prices()

Pingback: cialis()

Pingback: loperamide 2 mg pharmacy()

Pingback: generic cialis india()

Pingback: viagra commercial()

Pingback: order cefixime()

Pingback: cialis headaches afterwards()

Pingback: cheap cialis()

Pingback: propranolol uk()

Pingback: que es mejor cialis o viagra()

Pingback: buy viagra in malaysia()

Pingback: top essay writing services uk()

Pingback: writing a research questions()

Pingback: what should i write my essay on()

Pingback: help me write a good intro to my essay()

Pingback: current business ethics issues essay()

Pingback: clubhouse invite()

Pingback: cost of lamotrigine 200mg()

Pingback: buy digoxinmg()

Pingback: overseas pharmacies shipping to usa()

Pingback: augmentin 500mg 125mg()

Pingback: buy augmentin online()

Pingback: lasix price india()

Pingback: viagra over the counter walmart()

Pingback: zithromax buying()

Pingback: ivermectin 50()

Pingback: combivent cost price()

Pingback: gemfibrozil 300 mg nz()

Pingback: when will viagra be generic()

Pingback: viagra without a doctor prescription()

Pingback: buy zithromax online with mastercard()

Pingback: metoprolol online pharmacy()

Pingback: over the counter viagra()

Pingback: img()

Pingback: img1()

Pingback: uti doxycycline()

Pingback: dosing for doxycycline()

Pingback: how to buy clotrimazole()

Pingback: prednisolone warnings()

Pingback: online pharmacy clomid()

Pingback: dapoxetine hydrochloride buy()

Pingback: diflucan effectiveness()

Pingback: diflucan prescription online()

Pingback: synthroid 250 mcg()

Pingback: liga spravedlivosti 2021()

Pingback: order ed pills()

Pingback: how much is zithromax 250 mg()

Pingback: neurontin 300 mg tablets()

Pingback: 666()

Pingback: zithromax prescription in canada()

Pingback: propecia regrow hair()

Pingback: write my essays()

Pingback: cialis without perscription canada pharmacy()

Pingback: cheapest cialis in australia()

Pingback: reputable online pharmacies in india()

Pingback: neurontin vs gabapentin()

Pingback: metformin toxicity()

Pingback: paxil for anxiety()

Pingback: order medications online from india()

Pingback: plaquenil vs chloroquine()

Pingback: plaquenil dose calculator()

Pingback: cialis pills()

Pingback: buying viagra online without prescription()

Pingback: pas cher viagra soft 50 en online()

Pingback: levitra online amazon australia()

Pingback: The Revenant()

Pingback: clomid online no prescription()

Pingback: cialis erection australia()

Pingback: sailor moon viagra commercial()

Pingback: how to get cialis online australia()

Pingback: viagra online 200mg()

Pingback: amoxicillin no prescription()

Pingback: 2021()

Pingback: dosage for amoxicillin for cats()

Pingback: amoxicillin adverse reactions()

Pingback: azithromycin for prostatitis()

Pingback: celecoxib 200 mg()

Pingback: metformin 500 buy()

Pingback: printable celebrex coupons()

Pingback: impetigo keflex()

Pingback: cephalexin 500mg cap teva()

Pingback: cymbalta complications()

Pingback: trileptal and cymbalta()

Pingback: viagra on sale()

Pingback: acheter femalle cialis()

Pingback: cialis store australia()

Pingback: cialis video italiano()

Pingback: 200 mg viagra online()

Pingback: 200 mg viagra()

Pingback: 100mg viagra cost()

Pingback: sildenafil fast shipping()

Pingback: viagra pill cheap()

Pingback: D4()

Pingback: buy tadalafil pills()

Pingback: cost of propecia()

Pingback: discount cialis 40 mg()

Pingback: sildenafil pharmacy prices()

Pingback: teva viagra generic()

Pingback: is propecia a prescription drug()

Pingback: sildenafil prices 20 mg()

Pingback: cialis generic best price australia()

Pingback: cialis black generico()

Pingback: 777()

Pingback: levitra generic south africa()

Pingback: viagra purchase in india()

Pingback: sildenafil 100mg price comparison()

Pingback: walmart otc cialis()

Pingback: generic cialis over the counter cvs()

Pingback: levitra vs sildenafil()

Pingback: sildenafil soft 100mg()

Pingback: otc version of cialis()

Pingback: cheaeneric viagra free shipping()

Pingback: buy sildenafil tablets online()

Pingback: buy cialis online generic()

Pingback: canadian pharmacy meds()

Pingback: cures for ed()

Pingback: non prescription ed pills()

Pingback: lasix pills()

Pingback: viagra canada()

Pingback: online pharmacy discount code()

Pingback: link()

Pingback: cost of cialis without insurance()

Pingback: Zakhar Berkut hd()

Pingback: 4569987()

Pingback: cialis original for sale()

Pingback: cialis quebec dollars canadien()

Pingback: cialis soft tablet()

Pingback: 20 mg cost()

Pingback: news news news()

Pingback: payday loan provider()

Pingback: psy()

Pingback: psy2022()

Pingback: projectio-freid()

Pingback: viagra without a doctor prescription()

Pingback: isotretinoin cialis()

Pingback: Google()

Pingback: payday loans in michigan()

Pingback: What is tinder All about()

Pingback: cash advance payday loan downey()

Pingback: viagra regelmäßig einnehmen()

Pingback: kinoteatrzarya.ru()

Pingback: topvideos()

Pingback: buy toronto()

Pingback: where can i order lisinopril online()

Pingback: buy 20mg lisinopril()

Pingback: buy toronto()

Pingback: afisha-kinoteatrov.ru()

Pingback: Ukrainskie-serialy()

Pingback: free adult dating chat()

Pingback: site()

Pingback: cialis generic canada pharmacy()

Pingback: buy cialis rush()

Pingback: can i buy ativan in mexico()

Pingback: top()

Pingback: cialis no perscription()

Pingback: canadian pharmacies legitimate()

Pingback: cialis without prescribtion()

Pingback: cialis for daily use()

Pingback: where can i buy original cialis()

Pingback: order original cialis online()

Pingback: order original cialis online()

Pingback: real dildo()

Pingback: mobile homes for sale in westmoreland county pa()

Pingback: buy cialis 36 hour()

Pingback: canadian drugs online pharmacies()

Pingback: online pharmacy tadalafil()

Pingback: Short guns for sale()

Pingback: buy cialis online cheap()

Pingback: cialis 20 mg from canada()

Pingback: women using bizarre sex toys()

Pingback: everyday life of a sex toy reviewer()

Pingback: Glock 48 for sale()

Pingback: natural drugs for ed()

Pingback: pendik kaynarca escort()

Pingback: canadapharmacy.com()

Pingback: slot online()

Pingback: order valtrex online canada()

Pingback: electric motorbike canada()

Pingback: cialis 50 mg()

Pingback: interesting facts about sex()

Pingback: anal training toys()

Pingback: sildenafil otc()

Pingback: non prescription medicine pharmacy()

Pingback: Buy Weed Online()

Pingback: lesbian strapon()

Pingback: mens erection pills()

Pingback: viagra wiki()

Pingback: best sex games()

Pingback: best treatment for ed()

Pingback: cost of cialis()

Pingback: tadalafil 20mg()

Pingback: g gasm g spot vibrator()

Pingback: marley generics viagra()

Pingback: viagra amazon()

Pingback: cialis black australia()

Pingback: viagra online order()

Pingback: batman pinball machine()

Pingback: Buy Weed Online()

Pingback: PARROTS FOR SALE()

Pingback: Best software()

Pingback: ATTA CHAKKI()

Pingback: soderzhanki-3-sezon-2021.online()

Pingback: doxycycline online()

Pingback: best kratom capsules()

Pingback: chelovek-iz-90-h()

Pingback: best kratom()

Pingback: podolsk-region.ru()

Pingback: buy Instagram likes()

Pingback: best delta 8 thc gummies()

Pingback: adam and eve discount codes()

Pingback: viagra without a doctor prescription usa()

Pingback: п»їviagra pills()

Pingback: tides today at tides.today()

Pingback: cytotmeds.com()

Pingback: errectile disfunction()

Pingback: Company Formation()

Pingback: bender na4alo 2021()

Pingback: blogery_i_dorogi()

Pingback: blogery_i_dorogi 2 blogery_i_dorogi()

Pingback: best male enhancement()

Pingback: can i buy prednisone over the counter in spain()

Pingback: new erectile dysfunction treatment()

Pingback: Marijuana Gummies()

Pingback: buy delta 8 THC()

Pingback: weed near me()

Pingback: hydroxychloroquine canada for sale()

Pingback: ivermectin new zealand()

Pingback: dapoxetine and viagra()

Pingback: priligy oral liquid()

Pingback: christian dating for free elevate options()

Pingback: hydroxychloroquine 400 mg()

Pingback: realistic stroker()

Pingback: waterproof vibrator()

Pingback: buy weed()

Pingback: buy weed()

Pingback: ivermectin 3mg()

Pingback: buy weed()

Pingback: tiktok followers()

Pingback: how to buy guns online()

Pingback: thc vape cartridges for sale()

Pingback: ivermectin coronavirus()

Pingback: Data obligasi()

Pingback: ivermectin lotion for lice()

Pingback: MURANG'A UNIVERSITY()

Pingback: ivermectin price comparison()

Pingback: medication for ed dysfunction()

Pingback: doctors say hydroxychloroquine works()

Pingback: drug store online()

Pingback: chernaya vodova()

Pingback: 66181()

Pingback: hydroxychloroquine nyc trial results()

Pingback: online prescription for ed meds()

Pingback: escort bayan()

Pingback: Parksville Roofing Company()

Pingback: Respawn 110 Gaming Chair()

Pingback: armadillo girdled lizards for sale()

Pingback: Porno()

Pingback: vechernyy urgant()

Pingback: ukraine()

Pingback: 50 beowulf ammo()

Pingback: buy viagra online canada()

Pingback: best over the counter viagra()

Pingback: how to get rid of love handles()

Pingback: can i buy cialis in toronto()

Pingback: A3ixW7AS()

Pingback: cialis online daily()

Pingback: hydroxychloroquine 5 mg()

Pingback: hydroxychloroquine over the counter for humans()

Pingback: top sex toys()

Pingback: Canadian service()

Pingback: gidonline-ok-google()

Pingback: Cryptocurrency HBCUC()

Pingback: cucumber juul pods()

Pingback: معرفة هوية المتصل()

Pingback: larry bird kush()

Pingback: Buy Ruger Guns Online USA()

Pingback: KremlinTeam()

Pingback: medunitsa.ru()

Pingback: kremlin-team.ru()

Pingback: psychophysics.ru()

Pingback: yesmail.ru()

Pingback: plaquenil 200 mg price uk()

Pingback: cialisorigina()

Pingback: Suicide Squad 2()

Pingback: psiholog()

Pingback: paypal buy viagra()

Pingback: hydroxychloroquine malaria drug()

Pingback: male masturbator review()

Pingback: penis enlarger()

Pingback: chinese herb viagra()

Pingback: hizhnyak-07-08-2021()

Pingback: buy real viagra online()

Pingback: canadian pharmacies that are safe()

Pingback: zithromax online usa no prescription()

Pingback: MKsOrb.Com()

Pingback: how much does viagra cost at walmart()

Pingback: vaccine()

Pingback: canadian pharmacy meds.com()

Pingback: wand massager()

Pingback: AMI Hospital Management()

Pingback: anadolu yakasi escort()

Pingback: ivermectil for blood pressure treatment()

Pingback: ben wa balls review()

Pingback: thrusting sex toy()

Pingback: ivermectin generic()

Pingback: prostate vibrator()

Pingback: regcialist.com()

Pingback: stromectol otc()

Pingback: natural remedies for ed()

Pingback: canadian pharmacy 365()

Pingback: plaquenil online mexico()

Pingback: buy weed in Houston()

Pingback: fun88()

Pingback: wearable panty vibrator()

Pingback: vibrating pocket masturbator()

Pingback: female vacuum pump()

Pingback: Realistic Maturbator()

Pingback: hosting deals()

Pingback: how to make homemade cialis()

Pingback: MILF Porn()

Pingback: ground leases()

Pingback: viagra buy()

Pingback: สมัคร lottovip()

Pingback: ruay lotto()

Pingback: dapoxetine tablets in india()

Pingback: where can i get prednisone()

Pingback: male prostate vibrator()

Pingback: adam and eve dildo()

Pingback: how to masturbate using a huge dildo()

Pingback: سكس في الغسالة()

Pingback: Thc jull pods()

Pingback: potassium antiparasitic()

Pingback: gungoren escort()

Pingback: Peer-To-Peer Lending And Borrowing Protocol()

Pingback: vehicle repatriation()

Pingback: site de streaming()

Pingback: streaming gratuit()

Pingback: film streaming()

Pingback: melhores telemóveis()

Pingback: viagra sildenafil 25 mg()

Pingback: CTRLCOIN()

Pingback: download twitter video()

Pingback: how long does it take for atorvastatin to get out of your system()

Pingback: best male stroker()

Pingback: where can i buy viagra or cialis()

Pingback: sex toy myths and facts()

Pingback: masturbation toys()

Pingback: how to use cock ring()

Pingback: thrusting rabbit vibrator()

Pingback: male stroker toy()

Pingback: w88()

Pingback: quetiapine 250 mg()

Pingback: stromectol for eye infection()

Pingback: ed pills from canada()

Pingback: best in ottawa()

Pingback: cosmos public school vasundhara enclave()

Pingback: diazepam interaction with duloxetine()

Pingback: ruger 10 22 carbine for sale()

Pingback: 메이저사이트()

Pingback: 피망포커머니()

Pingback: what is hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg used for?()

Pingback: viagra alternative()

Pingback: ivermectin 90 mg()

Pingback: atorvastatin side effects liver()

Pingback: viagra buy online()

Pingback: zoloft acid reflux()

Pingback: Murchison Falls Wildlife()

Pingback: erectile dysfunction medications()

Pingback: pain meds without written prescription()

Pingback: ariel()

Pingback: discount cialis online()

Pingback: buy big chief carts()

Pingback: cialis 20 mg tablet()

Pingback: cialis uk()

Pingback: stromectol in dentistry()

Pingback: Macaw for sale near me()

Pingback: buy discount cialis()

Pingback: West Highland White Terrier()

Pingback: ADDERALL FOR SALE()

Pingback: www.viagrakari.com()

Pingback: Duna 2021()

Pingback: Morley Academy()

Pingback: online pharmacy usa()

Pingback: free viagra()

Pingback: clit sucking vibrator()

Pingback: handjob stroker()

Pingback: projektant wnętrz Gdynia()

Pingback: duloxetine generic brands()

Pingback: pc app free download()

Pingback: viagra pill()

Pingback: free download for pc()

Pingback: buy stromectol 6mg usa()

Pingback: laptop app free download()

Pingback: free download for pc windows()

Pingback: function of stromectol()

Pingback: pc games for windows 10()

Pingback: how do you get cialis()

Pingback: free download for windows 8()

Pingback: juicy mp3()

Pingback: download app apk for windows()

Pingback: 1()

Pingback: order viagra online()

Pingback: where can buy viagra()

Pingback: sugar gliders for sale near me()

Pingback: Agence de publicite()

Pingback: IT Support Bristol()

Pingback: viagra purchase buy()

Pingback: Order Sig Sauer Firearms Online()

Pingback: amoxiclav 875()

Pingback: cialis for daily use()

Pingback: buy cheap clomid()

Pingback: Mac air akku reparatur pfäffikon()

Pingback: Pinball Machines for Sale()

Pingback: Shipping containers For Sale()

Pingback: Gorilla trekking Rwanda ()

Pingback: ivermectin 1mg()

Pingback: viagra otc()

Pingback: how to buy cialis online()

Pingback: Macbook pro akku service rapperswil()

Pingback: hair thinning finasteride()

Pingback: ivermectin 1 topical cream()

Pingback: 3 Days volcanoes gorilla tour()

Pingback: doxycycline mono()

Pingback: prednisone 10mg no prescription()

Pingback: best doc johnson sex toys()

Pingback: FARMING EQUIPMENT FOR SALE NEAR ME()

Pingback: shipping containers for sale()

Pingback: cheap generic viagra online()

Pingback: Serengeti African safari()

Pingback: ارقام بنات()

Pingback: aromatherapy company()

Pingback: tadalafil india 1mg()

Pingback: is ivermectin safe for people()

Pingback: viagra cream australia()

Pingback: cialis no prescription overnight delivery()

Pingback: order viagra pills()

Pingback: ivermectin dose()

Pingback: cialis usa prescription()

Pingback: how long before sex should you take cialis()

Pingback: can you buy viagra in mexico over the counter()

Pingback: walmart price for cialis()

Pingback: izrada web sajtova()

Pingback: lowes employee login()

Pingback: cialis capsule()

Pingback: ivermectin drug()

Pingback: ivermectin prostate cancer()

Pingback: generic z pack over the counter()

Pingback: female viagra in india online purchase()

Pingback: Buy Ketamine online()

Pingback: viagra with script()

Pingback: do i need a prescription to buy ventolin()

Pingback: recommended canadian viagra rx online()

Pingback: ivermectin dosage for scabies in humans()

Pingback: TRIPLE HEX CARTS()

Pingback: viagra australia no prescription()

Pingback: dosage of ivermectin for dogs()

Pingback: purple triangle generic viagra 100 mg()

Pingback: savage impulse hog hunter 300 win()

Pingback: ivermectin horse()

Pingback: perscription viagra online pick up at drugstore()

Pingback: winchester pdx1 12 gauge()

Pingback: sig sauer p320 x carry()

Pingback: taurus pt92()

Pingback: hudson shuffleboards for sale()

Pingback: mossberg 930 deer waterfowl combo()

Pingback: cialis side effects()

Pingback: pentobarbital for sale()

Pingback: how to fix ed()

Pingback: stiiizy battery alternative Archives()

Pingback: psychological ed treatment()

Pingback: magic mushrooms()

Pingback: magic mushrooms()

Pingback: cialis generique()

Pingback: canadian medications()

Pingback: buy zithromax online cheap()

Pingback: stromectol is for()

Pingback: buy genetic viagra sites that take paypal()

Pingback: best background check()

Pingback: buy marijuana online california()

Pingback: canadian pharmacy online cialis()

Pingback: sildenafil sandoz()

Pingback: mexican pharmacy online()

Pingback: sildenafil 20mg()

Pingback: juul pods for sale()

Pingback: lisinopril and the kidneys()

Pingback: ivermectin expiration date()

Pingback: long term payday loans direct lender()

Pingback: beretta 85fs cheetah for sale()

Pingback: marble fox for sale()

Pingback: new slots()

Pingback: s&w 642 for sale()

Pingback: ROVE CARTS()

Pingback: bohemian coffee table()

Pingback: viagra generic online()

Pingback: ejaculatio praecox dapoxetine()

Pingback: exotic cannabis for sale()

Pingback: stromectol 12mg()

Pingback: bitcoin mining machine for sale in australia()

Pingback: How to Book a Safari to Murchison Falls Uganda?()

Pingback: d33006 video card()

Pingback: nolvadex pct()

Pingback: nautilus counter()

Pingback: nolvadex d()

Pingback: tamoxifen vs clomid()

Pingback: وكالة تسويق()

Pingback: prednisone cream()

Pingback: G17 GEN 4 MOS STANDARD | 9X19MM()

Pingback: Drd Tactical ()

Pingback: understanding stock market()

Pingback: prednisone 10mg tabs()

Pingback: buy adhd online uk()

Pingback: RissMiner()

Pingback: ivermectin price usa()

Pingback: Sig Sauer Gunshop()

Pingback: Little Parndon Primary School()

Pingback: dizziness()

Pingback: ivermectin eye drops()

Pingback: ivermectin lotion cost()

Pingback: bitcoin()

Pingback: ava archer syme-reeves()

Pingback: azithromycin over the counter cvs()

Pingback: canadian online drugstore()

Pingback: Uganda Tour()

Pingback: generic ivermectin cream()

Pingback: cost of stromectol()

Pingback: canadian online drugs()

Pingback: canadian pharmacy generic viagra()

Pingback: legal to buy prescription drugs without prescription()

Pingback: Safari to Uganda()

Pingback: beretta guns()

Pingback: savage grow plus reviews()

Pingback: azithromycin over the counter for chlamydia()

Pingback: thc vape carts for sale()

Pingback: sig sauer firearms()

Pingback: ltakside sikin beni()

Pingback: how to masturbate using a realistic pocket stroker()

Pingback: best male stokers()

Pingback: BUY WEED ONLINE()

Pingback: radom ak()

Pingback: viagra fast shipping()

Pingback: Patek Philippe()

Pingback: viagra side effects()

Pingback: dank vape carts for sale()

Pingback: viagra no prescription uk()

Pingback: via without doctor prescription()

Pingback: online pharmacy()

Pingback: can i buy prednisone over the counter in usa()

Pingback: raw garden cartridges()

Pingback: prednisone cost us()

Pingback: buying viagra()

Pingback: MUT()

Pingback: online viagra cheap()

Pingback: happyLuke()

Pingback: drug test with prescription()

Pingback: ivermectin 5 mg price()

Pingback: buy amoxil uk()

Pingback: alternatives to viagra()

Pingback: amoxicillin 250 mg()

Pingback: furosemide cost()

Pingback: drug lasix 40 mg()

Pingback: gabapentin 900 mg()

Pingback: brand name neurontin()

Pingback: plaquenil online()

Pingback: prednisone from india()

Pingback: buy high quality counterfeit money online()

Pingback: canadian viagra()

Pingback: priligy online india()

Pingback: viagra tablets()

Pingback: dapoxetine generic()

Pingback: provigil to buy()

Pingback: ivermectin 6mg()

Pingback: hydroxychloroquine for sale india()

Pingback: stromectol cream()

Pingback: ventolin hfa price()

Pingback: azithromycin treats()

Pingback: cucumber juul pods()

Pingback: zithromax cost()

Pingback: viagra canada()

Pingback: walgreens viagra()

Pingback: stromectol over the counter for sale()

Pingback: sildenafil otc uk()

Pingback: best testosterone booster()

Pingback: prednisone 80 mg()

Pingback: Najam vozila Crna Gora()

Pingback: ventolin 500 mcg()