To succeed under pressure we have to trust.

Every day brings the same routine for the Royal Air Force’s pilots. Wait. Stare at magazines, but never turn the pages. Watch the hands twitch around the clock face.

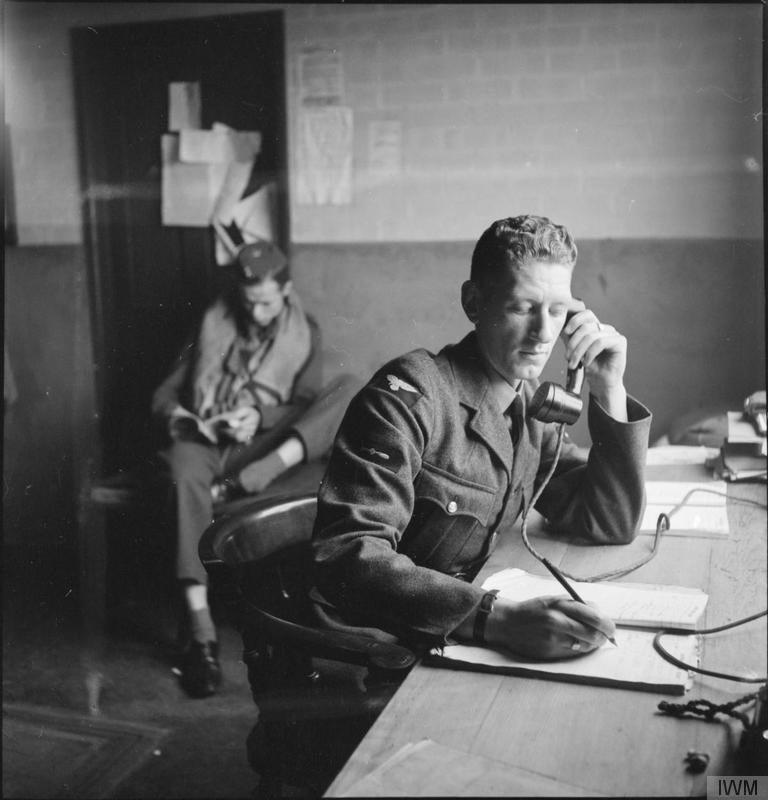

As the morning wears on the pilots think, “It’s almost too late, the Germans won’t be coming.” But invariably they hear that sound, the momentary, almost-silent click of the relay that always precedes the phone by a fraction of a second. Twelve faces look up. And then the ring.

Tense silence, broken by the orderly. “Squadron scramble, base angels twelve!”

The routine breaks and adrenaline begins to heighten these young men’s senses.

“Go! Start up! Move! Move!”

Everyone runs for the door, sprints over dew-slicked grass down the line of planes.

All twelve Spitfires on the runway are ready to fly. They have been since dawn. Every morning, while the pilot choke down toast and sip strong tea, their ground crew is prepping the twelve planes as though battle is a certainty. They repair damage from the day before and warm up the engines. By dawn, when the pilots are finished with breakfast and come to the airfield for dispersal, they are greeted by twelve planes’ Merlin engines, 144 cylinders crackling and roaring in unison.

Now, with the enemy approaching, pilots snatch their parachutes and with trembling fingers struggle to adjust the straps and buckles. They have one job, shoot down German planes. And every person at the airfield who isn’t flying a plane is playing a role to ensure the boys in the cockpits can focus on their singular task.

Riggers, the slang name for ground crew, are doing the final checks on the cockpit instruments. They clear out of the way as the pilots clamber up the wing and leap into the cockpit.

The riggers are already out on the wing, bracing against the propeller’s slip-wash, holding over the pilots shoulders the sutton straps that will anchor the pilots firmly in their seats against the powerful g-forces that will tear at them as they bank and dive. They ram pins into the harnesses, locking the pilots in place. The canopies slam shut and the noise outside fades.

Each pilot does a last double-check. Propeller pitch set to fine…radiator lever on the floor, the open position. Merlins overheat easily in the Spit but the ground crew knows their jobs.

The pilots turn to the riggers now standing by the wingtips. The men who will be staying on the ground offer a quick salute and pull the chocks away from the wheels.

Throttles forward. The Spitfires tremble. Rolling across the grass, the squadron leader’s voice crackles over the radio.

“OK Gannic squadron, here we go.”

They don’t yet know where they’re going. No time for briefings before hand. They will get that information once they’re in the air. That’s standard, and every man saying goodbye to Britain, hopefully not for the last time, is accustomed to heading skyward with no idea where the battle is.

Advance the throttle slowly, all eyes on the leaders’ wing to keep spacing. Racing across the grass now, the tails lift off the ground. Steady…steady. Just a few seconds longer, then into the air. Twelve aircraft take off in unison, racing above the airfield. Landing gear up and turning left. Throttles set to climb and the squadron claws desperately into the sky.

Eleven planes follow their leader in tight formation as they wait for guidance from Sector Headquarters. As they climb the Sector Controller’s voice cuts through the engine noise, his voice calm over the radio.

“Gannic leader, this is Sapper. One hundred fifty plus bandits approaching Dungeness. Vector 120 degrees.”

“Ok Sapper, turning 120 degrees,” the squadron leaders voice replies over the static.

The squadron turns in formation and climbs through the clouds, concentrating on their neighbors’ wingtips as the minutes pass. The Sector Controller is tracking them on his map table, bringing them closer to the Germans. The fliers, and Britain herself, depend on the controller’s accuracy to guide them to the enemy.

“Gannic leader, this is Sapper. You’re getting close now. Vector 140.”

“Turning 140.”

The pilots watch their compasses as they swing in unison through 140 degrees. They pass 12,000 feet…14,000 feet. Their engines straining to pull the planes higher, to gain the advantage. Twelve pairs of eyes dart across the sky, straining to spot the raiders.

“Gannic leader, Sapper. They should be off to your left.” All eyes turn, and rising above the clouds a massive formation of black specks.

The radio crackles. The squadron leader cries out, “Tally ho! Tally ho! I see them! They’re at 15,000 feet and there are hundreds of the buggers!”

“Thank you, Gannic leader, good luck!”

The Sector Controller puts his microphone down. His job is finished.

The pilots switch on their gunsights and push the throttles forward. Engine roar fills the cockpit. Twelve planes half-roll into a diving attack. It’s all up to the pilots now.

Action This Day

Trust was the RAF’s lifeblood. The squadron pilots had to be in the air in less than two minutes. To launch that fast they had to put their faith in their ground crews to ready their planes. As a pilot, I find it astounding that they climbed into a high performance, 1000 horsepower fighter and took off without performing their own rigorous preflight inspection. But they did not have time; they had to place their trust in the crews.

Once airborne the pilots had no idea where to go and were completely dependent on the Sector Headquarters to guide them to the Germans. They relied on the Sector Controller, a man on the ground, standing over a map and radioing directions, to guide them safely. And that man relied on all the people in the Dowding System to give him the right information so that he could do so. So in the end twelve pilots were hurtling blindly through the sky in the fastest planes in the world, with their lives in the hands of hundreds of people who were all trusted to do their job. Without that trust, the system would have collapsed. The British simply did not have time or resources to operate otherwise.

It is easy to say trust is important. Instinctively we know that any organization needs a solid foundation in trust. But how do you build that trust as a leader, between you and your employees? Even harder, how do you encourage your employees to trust each other? They are expected to both work together and compete with each other. Building strong trust is tougher than a weekend retreat or a clever speech.

Here are a few things I think the RAF did well to encourage and build this trust.

They created a common purpose. The Battle of Britain was a fight for survival that gave every man and woman in the RAF a common cause. Obviously, in our organizations we probably aren’t grappling with life and death issues, but what can we do as leaders to define a common purpose and instill a sense of shared struggle?

They built relationships. Although it was not an official regulation, pilots were expected to visit with and forge relationships with their ground crew. Pilots would not dare miss checking on their riggers and fitters (invariably still working to patch up the “kite” for tomorrow’s missions) before turning in for the night. These actions built strong relationships. The ground crew understood not just the importance of their jobs, but they knew the person behind it. It made them far less likely to cut corners or take shortcuts that would endanger someone that needed their help. But how often do we encourage the people we lead to forge these types of relationships? How often do we encourage our people to take care of each other?

They encouraged transparency across all groups. Group Commanders encouraged their pilots to visit the Sector Headquarters Operations Rooms when off duty, to meet the people who worked there and see what they did. The pilots learned how they processed information, how they relayed directions to flyers and their strengths and limitations. It ensured the people providing essential information to pilots about where and how to fight were more than disembodied voices in the RAF flyboys’ earphones.

How often do we encourage this type of transparency in our organizations? Not the surface level transparency we give lip service to, not just cc’ing people on emails, but the deep insight into how our organizations function. Real trust can only come from knowing, and accepting, both the good and bad.

These are just three things I see in the Battle of Britain that helped the RAF build trust. What other factors do you see in this story? What else do you do as a leader to develop trust in your organizations?

Pingback: Pharmacy viagra()

Pingback: cialis 20 mg price()

Pingback: cialis price costco()

Pingback: generic cialis india()

Pingback: Viagra mail order usa()

Pingback: Buy viagra with discount()

Pingback: albuterol inhaler()

Pingback: when will generic cialis be available()

Pingback: www.cialis.com()

Pingback: where to buy cialis()

Pingback: cialis 10mg()

Pingback: viagra cialis()

Pingback: cialis generic name()

Pingback: buy tylenol online()

Pingback: buy viagra soft()

Pingback: online pharmacy viagra()

Pingback: female viagra()

Pingback: cheap viagra()

Pingback: online pharmacy viagra()

Pingback: otc ed pills()

Pingback: over the counter erectile dysfunction pills()

Pingback: viagra pharmacy 100mg()

Pingback: best ed pills()

Pingback: where to buy hydroxychloroquine()

Pingback: canadian pharmacy()

Pingback: canadian pharmacy()

Pingback: Viagra or cialis()

Pingback: Real cialis online()

Pingback: buy vardenafil online()

Pingback: vardenafil 20 mg()

Pingback: vardenafil online()

Pingback: cheapest ed pills online()

Pingback: online casino games for real money()

Pingback: online casino usa()

Pingback: natural viagra()

Pingback: online casino for real cash()

Pingback: casino games online()

Pingback: tadalafil 20 mg()

Pingback: cash payday()

Pingback: payday loans()

Pingback: loan online()

Pingback: viagra cost()

Pingback: online casino usa real money()

Pingback: sugarhouse casino online nj()

Pingback: new cialis()

Pingback: online casino us()

Pingback: top online casinos in the us()

Pingback: casino games online()

Pingback: buy cialis()

Pingback: usa pharmacy viagra()

Pingback: buy cialis()

Pingback: buy cialis()

Pingback: 20 cialis()

Pingback: slot machine()

Pingback: real money online casinos usa()

Pingback: gambling games()

Pingback: real money online casino()

Pingback: buy viagra()

Pingback: generic viagra names()

Pingback: viagra prices()

Pingback: generic viagra canada()

Pingback: cheap viagra generic()

Pingback: viagra without a doctor prescription()

Pingback: generic cialis reviews()

Pingback: best online pharmacy for viagra()

Pingback: viagra price()

Pingback: buy cialis generic online()

Pingback: buy viagra canada()

Pingback: generic for viagra()

Pingback: cialis prices()

Pingback: free slots()

Pingback: viagra without doctor()

Pingback: slots real money()

Pingback: can i buy viagra over the counter in england()

Pingback: where is safest online to buy viagra()

Pingback: order propecia()

Pingback: generic viagra pills()

Pingback: where to buy viagra online()

Pingback: generic viagra()

Pingback: cheap sildenafil()

Pingback: generic viagra()

Pingback: Viagra 25 mg for sale()

Pingback: cost of Viagra 25 mg()

Pingback: cheap sildenafil()

Pingback: Viagra 100 mg united states()

Pingback: buy online generic cialis()

Pingback: buy viagra online()

Pingback: viagra vs cialis()

Pingback: Cialis 80 mg tablet()

Pingback: how to purchase Cialis 60 mg()

Pingback: order cialis()

Pingback: canadian pharmacy viagra()

Pingback: buy cialis()

Pingback: order viagra()

Pingback: cheap viagra()

Pingback: where to buy Cialis 20 mg()

Pingback: how to buy Cialis 10 mg()

Pingback: Cialis 40 mg united kingdom()

Pingback: viagra()

Pingback: generic drugs()

Pingback: tadalafil 10 mg tablet()

Pingback: cheapest levitra 40mg()

Pingback: cheapest lasix 40 mg()

Pingback: furosemide 40mg purchase()

Pingback: canadian pharmacy no prescription needed()

Pingback: propecia 1 mg price()

Pingback: viagra canada()

Pingback: finasteride 5 mg without a prescription()

Pingback: where to buy viagra()

Pingback: abilify 15mg united states()

Pingback: viagra sans ordonnance en pharmacie()

Pingback: cost of actos 30mg()

Pingback: amaryl 4 mg nz()

Pingback: amoxicillin 500mg prices()

Pingback: antabuse 250mg canada()

Pingback: strattera 18mg medication()

Pingback: aricept 5 mg canada()

Pingback: buy viagra pills online()

Pingback: cialistodo.com()

Pingback: where to buy arimidex 1mg()

Pingback: cheap tadalafil()

Pingback: cialis voucher()

Pingback: buying prescription drugs from canada()

Pingback: avodart 0,5mg prices()

Pingback: liquid viagra online()

Pingback: benicar 40 mg australia()

Pingback: buy viagra()

Pingback: buy cialis online cheap()

Pingback: buy viagra online without script()

Pingback: cialis medication()

Pingback: sildenafil dosage recommendations()

Pingback: cheap viagra 100mg()

Pingback: cialis()

Pingback: viagra coupons()

Pingback: where to buy catapres()

Pingback: viagra()

Pingback: ceclor coupon()

Pingback: ceftin 250 mg generic()

Pingback: celebrex 100 mg online pharmacy()

Pingback: generic ed pills()

Pingback: celexa 10mg usa()

Pingback: cialis 20mg()

Pingback: cephalexin coupon()

Pingback: how to buy cipro()

Pingback: buy viagra()

Pingback: claritin 10 mg for sale()

Pingback: slot games()

Pingback: san manuel casino online()

Pingback: casino online games for real money()

Pingback: rivers casino()

Pingback: empire casino online()

Pingback: casino slots gambling()

Pingback: best ed treatments()

Pingback: online slots()

Pingback: online casinos()

Pingback: san manuel casino online()

Pingback: online casinos real money()

Pingback: owners car insurance()

Pingback: automobile insurance()

Pingback: amica car insurance quotes()

Pingback: cialis for sale()

Pingback: pharmacy in singaporeviagra()

Pingback: best insurance car()

Pingback: best car insurance rates()

Pingback: auto club insurance()

Pingback: direct line car insurance quotes()

Pingback: best pills for ed()

Pingback: non owner car insurance quotes()

Pingback: cheapest online car insurance quotes()

Pingback: geico car insurance quotes()

Pingback: sex and viagra()

Pingback: personal loans with no credit check()

Pingback: ed drugs online from canada()

Pingback: quick payday loans()

Pingback: Viagra original pfizer order()

Pingback: payday loans with no credit checks()

Pingback: fast installment loans()

Pingback: quick loans now()

Pingback: is it illegal to buy viagra online()

Pingback: bad credit loans florida()

Pingback: amoxicillin discount()

Pingback: male erection cream()

Pingback: payday loans()

Pingback: personal loans near me()

Pingback: cbd oil benefits and uses in books()

Pingback: reputable cbd oil companies()

Pingback: ananda professional cbd oil()

Pingback: where to buy cheap viagra()

Pingback: hempworks cbd oil()

Pingback: sildenafil 120 mg()

Pingback: what schedule is viagra()

Pingback: payday loans()

Pingback: 1 viagra pill()

Pingback: are cbd gummies a scam()

Pingback: side effects cbd oil benefits()

Pingback: sildenafil prices()

Pingback: cbd oil for sale colorado springs()

Pingback: cbd oil benefits 2016 usa()

Pingback: best online essay writing service()

Pingback: buy viagra online us pharmacy()

Pingback: essay writing services review()

Pingback: viagra manufacturer()

Pingback: essays writing()

Pingback: college essay writing service reviews()

Pingback: buy custom essays online()

Pingback: viagra 100mg tablet buy online()

Pingback: buying essays()

Pingback: buy papers online()

Pingback: top 10 essay writing services()

Pingback: essay paper writing services()

Pingback: viagra professional pfizer()

Pingback: cleocin no prescription()

Pingback: where to buy clomid 100 mg()

Pingback: Viagra overnight shipping()

Pingback: clonidine 0,1 mg united kingdom()

Pingback: where to buy clozaril()

Pingback: Canada viagra()

Pingback: how to buy colchicine()

Pingback: symbicort inhaler tablets()

Pingback: bayer cialis()

Pingback: combivent 50/20mcg nz()

Pingback: help write an essay()

Pingback: coreg pills()

Pingback: drugs from india()

Pingback: cialis()

Pingback: compazine 5 mg canada()

Pingback: coumadin 5mg no prescription()

Pingback: cozaar uk()

Pingback: Free viagra sample()

Pingback: writing a doctoral thesis()

Pingback: viagra ketoconazole()

Pingback: buy crestor 5mg()

Pingback: https://customessaywriterbyz.com()

Pingback: Viagra medication()

Pingback: how to purchase cymbalta 30 mg()

Pingback: college essay writing service reviews()

Pingback: cheap viagra()

Pingback: disertation()

Pingback: buy college research papers()

Pingback: dapsone caps over the counter()

Pingback: ddavp pharmacy()

Pingback: how to buy depakote 250 mg()

Pingback: how to purchase diamox 250 mg()

Pingback: differin coupon()

Pingback: diltiazem 30 mg without prescription()

Pingback: viagra prices()

Pingback: doxycycline for sale()

Pingback: dramamine online()

Pingback: elavil 10mg online pharmacy()

Pingback: canadian drug stores()

Pingback: cheapest erythromycin 500mg()

Pingback: etodolac australia()

Pingback: flomax 0,2mg otc()

Pingback: generic Cipro()

Pingback: flonase nasal spray 50mcg prices()

Pingback: garcinia cambogia 100caps price()

Pingback: ed doctors()

Pingback: geodon online pharmacy()

Pingback: hyzaar 12,5mg cheap()

Pingback: imdur usa()

Pingback: imitrex generic()

Pingback: generic cialis()

Pingback: what can i take to enhance cialis()

Pingback: cheap imodium()

Pingback: cialis side effects()

Pingback: canadian online pharmacy viagra()

Pingback: Click Here()

Pingback: prescription drugs from canada()

Pingback: buy real viagra online()

Pingback: imuran without a doctor prescription()

Pingback: do you need a prescription for viagra()

Pingback: where can i buy indocin 75mg()

Pingback: zithromax price canada()

Pingback: lamisil australia()

Pingback: order viagra generic()

Pingback: cheap levaquin 250mg()

Pingback: how to purchase lopid()

Pingback: buy viagra online()

Pingback: lopressor 50 mg australia()

Pingback: cheap macrobid()

Pingback: meclizine 25 mg online pharmacy()

Pingback: ed meds online without doctor prescription()

Pingback: cost of gnc viagra()

Pingback: mestinon 60 mg canada()

Pingback: discount pharmacies()

Pingback: micardis online pharmacy()

Pingback: cheap Valtrex()

Pingback: best canadian online pharmacy()

Pingback: mobic 7,5mg uk()

Pingback: canadian drug()

Pingback: erectile dysfunction()

Pingback: online pharmacy canada()

Pingback: motrin 200 mg generic()

Pingback: canada drugs()

Pingback: approved canadian pharmacies online()

Pingback: cheapest nortriptyline 25mg()

Pingback: where can i buy periactin 4mg()

Pingback: phenergan 25 mg purchase()

Pingback: plaquenil canada()

Pingback: prednisolone usa()

Pingback: prevacid coupon()

Pingback: where can i buy prilosec 10mg()

Pingback: how to buy proair inhaler 100mcg()

Pingback: cheap viagra()

Pingback: procardia pharmacy()

Pingback: cost of proscar 5mg()

Pingback: protonix 20 mg nz()

Pingback: provigil without a doctor prescription()

Pingback: post antibiotic world()

Pingback: pulmicort usa()

Pingback: bayviagra()

Pingback: doxycycline hydrochloride 100mg()

Pingback: pyridium 200 mg no prescription()

Pingback: where can i buy reglan()

Pingback: cheapest remeron()

Pingback: where to buy zyrtec 10mg online()

Pingback: retin-a cream 0.05% without prescription()

Pingback: how to buy revatio 20mg()

Pingback: cheapest risperdal 4 mg()

Pingback: allegra 30()

Pingback: robaxin usa()

Pingback: rogaine online pharmacy()

Pingback: seroquel australia()

Pingback: where to buy singulair()

Pingback: skelaxin australia()

Pingback: viagra for sale()

Pingback: tenormin without a prescription()

Pingback: buy generic 100mg viagra online()

Pingback: thorazine without a doctor prescription()

Pingback: toprol generic()

Pingback: tricor 200mg tablets()

Pingback: valtrex 500 mg uk()

Pingback: vantin without a doctor prescription()

Pingback: verapamil 40mg pills()

Pingback: voltaren 100mg tablet()

Pingback: cost of wellbutrin 300 mg()

Pingback: zanaflex 2mg united kingdom()

Pingback: how long does cialis 10mg last()

Pingback: look at this website()

Pingback: zocor 20 mg nz()

Pingback: purchase zithromax online()

Pingback: zovirax nz()

Pingback: zyloprim canada()

Pingback: zyprexa without prescription()

Pingback: to buy viagra in dubai()

Pingback: zyvox 600 mg prices()

Pingback: sildenafil canada()

Pingback: tadalafil 40mg usa()

Pingback: furosemide united kingdom()

Pingback: escitalopram nz()

Pingback: how to purchase aripiprazole 10 mg()

Pingback: buy amoxicillin online cheap()

Pingback: pioglitazone pills()

Pingback: spironolactone online pharmacy()

Pingback: canadian mail-order pharmacy()

Pingback: fexofenadine 180mg uk()

Pingback: buy glimepiride()

Pingback: meclizine 25mg uk()

Pingback: cheapest leflunomide()

Pingback: how to buy atomoxetine()

Pingback: buy donepezil 10 mg()

Pingback: anastrozole generic()

Pingback: viagra for sale()

Pingback: how to purchase irbesartan 300 mg()

Pingback: how to buy dutasteride 0,5mg()

Pingback: how to purchase olmesartan 40mg()

Pingback: buspirone online()

Pingback: clonidine 0.1 mg online()

Pingback: how to purchase cefuroxime()

Pingback: celecoxib for sale()

Pingback: citalopram 10mg united states()

Pingback: cephalexin medication()

Pingback: tadalafil()

Pingback: ciprofloxacin 750mg generic()

Pingback: buy cialis now()

Pingback: cialis prices at walmart()

Pingback: cialis 20 mg best price()

Pingback: loratadine usa()

Pingback: cialis online delivery overnight()

Pingback: clindamycin without a prescription()

Pingback: clozapine generic()

Pingback: order original cialis online()

Pingback: prochlorperazine 5 mg generic()

Pingback: generic viagra for ed()

Pingback: alternatives to viagra()

Pingback: buy cialis cheap canada()

Pingback: where can i buy carvedilol 12.5 mg()

Pingback: warfarin without a prescription()

Pingback: cheap rosuvastatin()

Pingback: desmopressin mcg tablet()

Pingback: divalproex tablets()

Pingback: tolterodine 1mg tablet()

Pingback: buy sildenafil in canada()

Pingback: safe buy cialis()

Pingback: acetazolamide cheap()

Pingback: pills like viagra()

Pingback: cialis delivery held at customs()

Pingback: fluconazole 100 mg coupon()

Pingback: order phenytoin()

Pingback: doxycycline for sale()

Pingback: buy bisacodyl()

Pingback: cheap generic viagra()

Pingback: generic cialis canadian()

Pingback: venlafaxine medication()

Pingback: can you buy viagra alternatives on ove rthe counter()

Pingback: amitriptyline 25mg no prescription()

Pingback: permethrin 30g usa()

Pingback: order cialis()

Pingback: erythromycin uk()

Pingback: buy cialis 5 mg online()

Pingback: canada cialis online()

Pingback: ppmnclwz()

Pingback: estradiol 1 mg otc()

Pingback: top rated ed pills()

Pingback: where to buy tamsulosinmg()

Pingback: best medication for ed()

Pingback: dgdpqkbf()

Pingback: the best ed pills()

Pingback: buy cialis canadian()

Pingback: erectile dysfunction drug()

Pingback: buy alendronate()

Pingback: how often can u take viagra()

Pingback: where to buy real viagra online()

Pingback: order viagra online()

Pingback: nitrofurantoin australia()

Pingback: wat is beter cialis of viagra()

Pingback: hoe werkt viagra pil()

Pingback: ivermectin is effective against which organisms?()

Pingback: how long can you take zithromax?()

Pingback: glipizide uk()

Pingback: lasix 20 mg()

Pingback: cialis online daily()

Pingback: viagra en espanol()

Pingback: nitrofurantoin price()

Pingback: isosorbide without a prescription()

Pingback: stromectol generic()

Pingback: buy augmentin()

Pingback: sumatriptan united states()

Pingback: tetracycline generic()

Pingback: loperamide 2 mg online pharmacy()

Pingback: cialis de 5mg()

Pingback: cheap cialis()

Pingback: viagra()

Pingback: significado de cialis()

Pingback: azathioprine 50mg medication()

Pingback: generic cialis no doctor's prescription()

Pingback: propranolol for sale()

Pingback: buy cialis shipping canada()

Pingback: 5mg cialis()

Pingback: comprar viagra online espaГ±a()

Pingback: indomethacin 50mg nz()

Pingback: viagra samples usa()

Pingback: essay writing services recommendations()

Pingback: buy cialis philippines()

Pingback: how to write an abstract for a research paper()

Pingback: who can write my essay()

Pingback: help with an essay()

Pingback: why is business ethics important free essay samples()

Pingback: buy cialis now()

Pingback: lamotrigine 25mg cheap()

Pingback: buy cialis now()

Pingback: terbinafine 250 mg online pharmacy()

Pingback: levofloxacin prices()

Pingback: buy cialis now()

Pingback: prescription drugs online without doctor()

Pingback: order levothyroxine mcg()

Pingback: buy viagra online canada()

Pingback: amoxicillin 750 mg price()

Pingback: furosemide 40 mg()

Pingback: order viagra online()

Pingback: zithromax over the counter canada()

Pingback: over the counter viagra()

Pingback: ivermectin online()

Pingback: albuterol medicine()

Pingback: generic viagra walmart()

Pingback: gemfibrozil 300 mg cost()

Pingback: zithromax for sale us()

Pingback: metoprolol cost()

Pingback: online doctor prescription for viagra()

Pingback: clotrimazole cost()

Pingback: doxycycline amazon()

Pingback: prednisolone 4mg()

Pingback: clomid pill()

Pingback: dapoxetine and cialis()

Pingback: diflucan free sample()

Pingback: synthroid levels()

Pingback: ed pills online()

Pingback: top ten essay writing services()

Pingback: can you buy zithromax over the counter in australia()

Pingback: neurontin 100mg cap()

Pingback: where can i buy zithromax capsules()

Pingback: proscar propecia()

Pingback: meds from india()

Pingback: online medications from india()

Pingback: neurontin side efects()

Pingback: cheap generic cialis in the us()

Pingback: metformin and surgery()

Pingback: paxil hci()

Pingback: plaquenil image()

Pingback: cialis pills online()

Pingback: viagra without a prescription()

Pingback: no prescription clomid()

Pingback: cialis with dapoxetine online()

Pingback: amoxicillin buy online canada()

Pingback: tadalafil online without prescription()

Pingback: metformin 850 mg india()

Pingback: drug cost metformin()

Pingback: cheap generic propecia()

Pingback: propecia 5mga()

Pingback: buy cheap cialis overnight()

Pingback: mens erection pills()

Pingback: best ed drug()

Pingback: lasix 90 20mg()

Pingback: trusted online pharmacy reviews()

Pingback: buy cialis 36 hour online()

Pingback: Zakhar Berkut hd()

Pingback: 4569987()

Pingback: canada cialis online()

Pingback: buy cialis united kingdom()

Pingback: fastest delivery of generic cialis()

Pingback: buy now()

Pingback: bootleg cialis()

Pingback: news news news()

Pingback: best payday loans bentonville()

Pingback: psy()

Pingback: psy2022()

Pingback: projectio-freid()

Pingback: female viagra()

Pingback: where to purchase tretinoin()

Pingback: allied cash advance shoreline()

Pingback: como comprar viagra en valencia()

Pingback: kinoteatrzarya.ru()

Pingback: topvideos()

Pingback: video()

Pingback: 20mg usa()

Pingback: lisinopril 20mg for sale()

Pingback: 20mg usa()

Pingback: prinivil 20mg tabs()

Pingback: afisha-kinoteatrov.ru()

Pingback: Ukrainskie-serialy()

Pingback: site()

Pingback: sex dating and relationships site free()

Pingback: where to buy ativan in uk()

Pingback: order original cialis online()

Pingback: how to avoid heartburn when taking cialis()

Pingback: top()

Pingback: is there a generic version of cialis()

Pingback: cialis generic for sale()

Pingback: taking cialis soft tabs()

Pingback: buy cialis cheaper online()

Pingback: giant food store pharmacy hours()

Pingback: online doctor prescription for cialis()

Pingback: canadian pharmacies-247()

Pingback: generic cialis prices()

Pingback: cialis online without prescription()

Pingback: meridia canadian pharmacy()

Pingback: where can u buy cialis()

Pingback: buy cialis very cheap prices fast delivery()

Pingback: ed drug prices()

Pingback: how much is valtrex in canada()

Pingback: online pharmacy without insurance()

Pingback: pills for erection()

Pingback: is ed reversible()

Pingback: 100mg viagra()

Pingback: soderzhanki-3-sezon-2021.online()

Pingback: buy amoxicillin 250mg()

Pingback: cytotmeds.com()

Pingback: chelovek-iz-90-h()

Pingback: podolsk-region.ru()

Pingback: buy doxycycline online 270 tabs()

Pingback: viagra online usa()

Pingback: 100mg viagra()

Pingback: viagra discount()

Pingback: fast ed meds online()

Pingback: bender na4alo 2021()

Pingback: blogery_i_dorogi()

Pingback: blogery_i_dorogi 2 blogery_i_dorogi()

Pingback: ed pills online pharmacy()

Pingback: prednisone 10 mg dose schedule()

Pingback: ivermectin over the counter()

Pingback: malaria hydroxychloroquine()

Pingback: discount coupon for priligy()

Pingback: ivermectin gel()

Pingback: plaquenil 150 mg()

Pingback: plaquenil medication()

Pingback: priligy tablets paris()

Pingback: ivermectin 2mg()

Pingback: stromectol liquid()

Pingback: buy ivermectin canada()

Pingback: hydroxychloroquine countries otc()

Pingback: best ed treatment pills()

Pingback: natural herbs for ed()

Pingback: chernaya vodova()

Pingback: 66181()

Pingback: do i have ed()

Pingback: american college rheumatology hydroxychloroquine()

Pingback: Porno()

Pingback: vechernyy urgant()

Pingback: ukraine()

Pingback: best place to buy generic viagra online()

Pingback: viagra cost()

Pingback: when will viagra be generic()

Pingback: monthly cost of cialis without insurance()

Pingback: A3ixW7AS()

Pingback: hydroxychloroquine o sulfate()

Pingback: hydroxychloroquine trade name()

Pingback: cost of cialis without insurance()

Pingback: gidonline-ok-google()

Pingback: link()

Pingback: KremlinTeam()

Pingback: medunitsa.ru()

Pingback: kremlin-team.ru()

Pingback: psychophysics.ru()

Pingback: yesmail.ru()

Pingback: hydroxychloroquine 200mg buy()

Pingback: plaquenil drug()

Pingback: 10 mg cialis for sale()

Pingback: generic cialis dapoxetine()

Pingback: Suicide Squad 2()

Pingback: hydroxychloroquine 200 mg tablet()

Pingback: viagra cheap master card()

Pingback: psiholog()

Pingback: antibiotics online pharmacy()

Pingback: buy viagra super force()

Pingback: hizhnyak-07-08-2021()

Pingback: when is viagra going generic()

Pingback: can you take viagra and cialis together()

Pingback: buy zithromax 1000 mg online()

Pingback: how much do prescription drugs cost without insurance?()

Pingback: zithromax 250 price()

Pingback: MKsOrb.Com()

Pingback: where can i buy zithromax medicine()

Pingback: best online pharmacies canada()

Pingback: ivermectil super active difference()

Pingback: regcialist.com()

Pingback: buy ivermectin uk()

Pingback: viagra drug class()

Pingback: ivermectin 3()

Pingback: best male enhancement()

Pingback: hydroxychloroquine tablets 10 mg()

Pingback: plaquenil 100 mg()

Pingback: how long before priligy works()

Pingback: buy cialis using paypal()

Pingback: when to take cialis for best results()

Pingback: generic cialis india()

Pingback: prednisone 50 mg canada()

Pingback: stromectol for parasite infestations()

Pingback: atorvastatin for high cholesterol()

Pingback: fluoxetine side effects cats()

Pingback: goodrx sertraline()

Pingback: quetiapine fumarate doses()

Pingback: lyrica vs gabapentin for fibromyalgia()

Pingback: recommended canadian online pharmacies()

Pingback: medication from canada prices()

Pingback: sildenafil online()

Pingback: atorvastatin calcium 20mg tablet()

Pingback: stromectol in uti()

Pingback: viagrahati.com()

Pingback: ivermect 875()

Pingback: buying viagra online()

Pingback: canadian pharmacy viagra()

Pingback: mail order cialis()

Pingback: where to order cialis online()

Pingback: stromectol 375()

Pingback: cialis 24 hours()

Pingback: escitalopram medication information()

Pingback: cialis usa()

Pingback: cialis pills for sale()

Pingback: cialis en ligne()

Pingback: generic viagra cheap no prescription()

Pingback: Duna 2021()

Pingback: sildenafil generic()

Pingback: 1()

Pingback: viagra coupon()

Pingback: stromectol 6mg for scabicide()

Pingback: sildenafil()

Pingback: duloxetine and addison's disease()

Pingback: viagra for sale online()

Pingback: sildenafil 50mg best price()

Pingback: generic viagra prices()

Pingback: amoxicillin 500 milligrams()

Pingback: cialis for men()

Pingback: natural viagra()

Pingback: buy propecia taiwan()

Pingback: cialis tadalafil online()

Pingback: order prednisone from canada()

Pingback: generic viagra cost()

Pingback: buy cialis in singapore()

Pingback: does ivermectin kill pinworms()

Pingback: cost of sildenafil 30 tablets()

Pingback: home page home page()

Pingback: ivermectin expiration date()

Pingback: cialis singapore()

Pingback: genuine viagra australia()

Pingback: cialis en ligne()

Pingback: zithramax oral()

Pingback: ivermectin for mange in foxes()

Pingback: ivermectin guinea pigs()

Pingback: viagra without a rx()

Pingback: ventolin inhalador precio()

Pingback: ivermectin sensitivity in dogs()

Pingback: viagra connect uk online()

Pingback: shoppers drug mart viagra price()

Pingback: female viagra sex videos()

Pingback: cialis superactive()

Pingback: tadalafil prescription()

Pingback: 20 mg cialis()

Pingback: ivermectin dosage for dogs for heartworm prevention()

Pingback: plaquenil for pregnant()

Pingback: nih ivermectin()

Pingback: viagra para hombres()

Pingback: where to buy viagra online without prescription forum()

Pingback: online viagra cheap()

Pingback: online pharmacy india()

Pingback: lisinopril dose too high()

Pingback: bad credit loans()

Pingback: no deposit bonus europa casino()

Pingback: online viagra prescription()

Pingback: dapoxetine sildenafil citrate in india()

Pingback: ivermectin for pinworms()

Pingback: order viagra canada pharmacy()

Pingback: buy viagra hyderabad india()

Pingback: get azithromycin over counter()

Pingback: stromectol dose for scabies()

Pingback: how quickly does ivermectin work()

Pingback: viagra alternative()

Pingback: azithromycin walgreens over the counter()

Pingback: generic viagra mail order()

Pingback: cialis vs viagra()

Pingback: cleantalkorg2.ru()

Pingback: viagra 100mg price usa()

Pingback: viagra no doctor prescription judpharm()

Pingback: viagra 20()

Pingback: order prescription viagra online()

Pingback: pfizer viagra()

Pingback: ed pills()

Pingback: doctor x viagra()

Pingback: buy amoxil 1000mg()

Pingback: female viagra pill()

Pingback: buy lasixonline()

Pingback: brand gabapentin()

Pingback: plaquenil singapore()

Pingback: 2.5 mg prednisone()

Pingback: avana 522()

Pingback: viagra for men()

Pingback: modafinil online()

Pingback: chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine for sale()

Pingback: ivermectin 10 ml()

Pingback: albuterol ipratropium()

Pingback: azithromycin price()

Pingback: lasix sale()

Pingback: stromectol for sale otc()

Pingback: non prescription online pharmacy reviews()

Pingback: can i purchase viagra over the counter()

Pingback: alternative to viagra()

Pingback: prednisone 5 mg pill()

Pingback: avana australia()

Pingback: provigil generic buy()

Pingback: ivermectin ireland()

Pingback: ventolin purchase()

Pingback: where to buy generic tadalafil()

Pingback: viagra para mujeres()

Pingback: viagra generic()

Pingback: where can i buy viagra over the counter in singapore()

Pingback: alternatives to viagra()

Pingback: viagra cost()

Pingback: viagra over the counter()

Pingback: virtual sex video games()

Pingback: cost of sildenafil 50mg()

Pingback: cialis viagra()

Pingback: hims viagra()

Pingback: goodrx sildenafil()

Pingback: hims sildenafil()

Pingback: stromectol for sale()

Pingback: viagra pills for men()

Pingback: achat cialis 20 mg()

Pingback: order viagra 50 mg()

Pingback: aabbx.store()

Pingback: california online casinos()

Pingback: pills that have sildenafil in them()

Pingback: ne-smotrite-naverx()

Pingback: pink viagra pills()

Pingback: arrogant()

Pingback: Dead-Inside()

Pingback: 20mg cialis daily()

Pingback: viagra buy thailand()

Pingback: online schools for pharmacy tech()

Pingback: sildenafil citrate tablets 100mg for sale()

Pingback: buy viagra online usa()

Pingback: marley generics viagra reviews()

Pingback: cialis purchase online canada()

Pingback: prednisone and cialis()

Pingback: cvs generic viagra()

Pingback: viagra dosages()

Pingback: stromectol liquid()

Pingback: can you buy ventolin over the counter in uk()

Pingback: stromectol 0.1()

Pingback: cialis professional()

Pingback: cialis controlled substance()

Pingback: sildenafil generic over the counter()

Pingback: viagra connect usa()

Pingback: ivermectin 2ml()

Pingback: ivermectin to buy()

Pingback: albuterol 2mg capsules()

Pingback: flccc ivermectin()

Pingback: covid care alliance()

Pingback: aralen and vision()

Pingback: bimatoprost cost()

Pingback: baricitinib lilly()

Pingback: canada pharmacy()

Pingback: nolvadex brand()

Pingback: molnupiravir generic()

Pingback: Anonymous()

Pingback: flcc blackboard login()

Pingback: ivermectin prescription()

Pingback: lilly baricitinib()

Pingback: ivermectin iv()

Pingback: buy stromectol online()

Pingback: where to buy ivermectin pills()

Pingback: ivermectin lotion for lice()

Pingback: stromectol uk()

Pingback: Anonymous()

Pingback: ivermectin 3mg tablets()

Pingback: ivermectin human()

Pingback: ivermectin 3()

Pingback: stromectol covid()

Pingback: Anonymous()

Pingback: ivermectin tablets for humans()

Pingback: where to get ivermectin()

Pingback: buy viagra generic online()

Pingback: ivermectin price()

Pingback: buy stromectol()

Pingback: stromectol price()

Pingback: flccc ivermectin()

Pingback: covid protocols()

Pingback: flccc ivermectin()

Pingback: imask protocol()

Pingback: ivermectin in india()

Pingback: 3rpUI4X()

Pingback: stromectol tablets()

Pingback: ignition casino on ipad()

Pingback: cialis price()

Pingback: canadian generic cialis online()

Pingback: uliocx()

Pingback: 34tfA26()

Pingback: 3J6w3bD()

Pingback: 3GrvxDp()

Pingback: 3rrZhf7()

Pingback: 3L1poB8()

Pingback: my-vse-mertvy-2022()

Pingback: meritroyalbet()

Pingback: madridbet()

Pingback: meritking()

Pingback: meritking()

Pingback: ivermectin australia()

Pingback: stromectol price()

Pingback: ivermectin ontario()

Pingback: stromectol medication()

Pingback: buy prednisone 5mg for sale()

Pingback: how to get cialis without a prescription()

Pingback: meritroyalbet()

Pingback: meritroyalbet()

Pingback: elexusbet()

Pingback: meritroyalbet()

Pingback: tadalafil walgreens()

Pingback: warnings for tadalafil()

Pingback: buy ventolin online no prescription()

Pingback: provigilcanadian pharmacy()

Pingback: provigil online usa()

Pingback: cialis price()

Pingback: ivermectin cream uk()

Pingback: buy viagra legally online()

Pingback: generic ivermectin cream()

Pingback: tadalafil vs sildenafil()

Pingback: generic viagra side effects()

Pingback: can you buy zithromax online()

Pingback: stromectol walmart canada()

Pingback: tadalafil liquid()

Pingback: northern pharmacy canada()

Pingback: where to get generic cialis()

Pingback: tadalafil generic where to buy()

Pingback: baymavi()

Pingback: baymavi()

Pingback: canadian drug prices()

Pingback: buy generic cialis with paypal()

Pingback: sildenafil citrate for sale()

Pingback: tadalafil generic name()

Pingback: tadalafil generic()

Pingback: ivermectin treatment()

Pingback: sildenafil pills online purchase()

Pingback: cheap sildenafil online in usa()

Pingback: generic cialis()

Pingback: cialis generic medication()

Pingback: generic for cialis()

Pingback: tombala siteleri()

Pingback: want to buy prednisone()

Pingback: get prednisone online()

Pingback: no prescription cialis canada()

Pingback: generic cialis prescription()

Pingback: antiviral medications for covid()

Pingback: 1holding()

Pingback: buy molnupiravir()

Pingback: tadalafil online india()

Pingback: tadalafil mylan()

Pingback: stromectol otc()

Pingback: meritroyalbet()

Pingback: eurocasino()

Pingback: ivermectina piojos()

Pingback: meritking()

Pingback: eurocasino()

Pingback: steroid side effects()

Pingback: what is sildenafil()

Pingback: cheap tadalafil()

Pingback: free casino slots real money()

Pingback: cost of stromectol medication()

Pingback: elexusbet()

Pingback: trcasino()

Pingback: cialis online()

Pingback: ivermectin us fda()

Pingback: ivermectin 0.5%()

Pingback: stromectol tablets()

Pingback: online casino gaming()

Pingback: marley generics cialis()

Pingback: cheap cialis india()

Pingback: overnight sildenafil()

Pingback: tadalafil cialis()

Pingback: ivermectin mexico()

Pingback: cost of ivermectin pill()

Pingback: cialis 5mg no prescription()

Pingback: ivermectin 12mg for sale()

Pingback: clomid 2020()

Pingback: ivermektin()

Pingback: canadian pharmacy no prescription cialis()

Pingback: Russia launches Ukraine()

Pingback: ivermectin 3mg tablets()

Pingback: z.globus-kino.ru()

Pingback: generic doxycycline()

Pingback: ivermectin tablets over counter()

Pingback: buy ivermectin online()

Pingback: stromectol xr()

Pingback: viagra dosage for 70 year old()

Pingback: buy cialis online()

Pingback: ivermectin tablets for humans for sale()

Pingback: http://andere.strikingly.com/()

Pingback: minocycline 50 mg tabs()

Pingback: ivermectin 0.5 lotion india()

Pingback: ivermectin 12mg tablets for human()

Pingback: buy ivermectin 3mg for sale()

Pingback: where to buy ivermectin()

Pingback: furosemide generic()

Pingback: cost of furosemide 40mg()

Pingback: cost of ivermectin()

Pingback: cialis buy india()

Pingback: ivermectin corona()

Pingback: ivermectin dose dogs()

Pingback: ivermectin use()

Pingback: ivermectin 400 mg()

Pingback: yutub()

Pingback: ivermectin can()

Pingback: madridbet giriş()

Pingback: luckyland slots casino sign in()

Pingback: where to buy cialis in canada()

Pingback: stromectol pill()

Pingback: https://kernyusa.estranky.sk/clanky/risk-factors-linked-to-anxiety-disorders-differ-between-women-and-men-during-the-pandemic.html()

Pingback: canadian pharmacy uk delivery()

Pingback: purchase ivermectin()

Pingback: https://graph.org/Omicron-Variant-Symptoms-Is-An-Excessive-Amount-Of-Mucus-A-COVID-19-Symptom-02-24()

Pingback: swerbus.webgarden.com()

Pingback: https://gpefy8.wixsite.com/pharmacy/post/optimal-frequency-setting-of-metro-services-within-the-age-of-covid-19-distancing-measures()

Pingback: cialis 20mg coupon()

Pingback: buy ivermectin cream()

Pingback: keuybc.estranky.skclanky30-facts-you-must-know--a-covid-cribsheet.html()

Pingback: https://gwertvb.mystrikingly.com/()

Pingback: telegra.phIs-It-Safe-To-Lift-COVID-19-Travel-Bans-04-06()

Pingback: https://graph.org/The-Way-To-Get-Health-Care-At-Home-During-COVID-19---Health--Fitness-04-07()

Pingback: hydroxychloroquine rash()

Pingback: online pharmacies()

Pingback: canadian-pharmacies0.yolasite.com()

Pingback: buy cialis online australia()

Pingback: https://pharmacy-online.yolasite.com/()

Pingback: smotretonlaynfilmyiserialy.ru()

Pingback: https://kevasw.webgarden.com/()

Pingback: 20mg cialis walmart()

Pingback: canadian pharmacy online()

Pingback: clomid for women()

Pingback: price of clomid uk()

Pingback: canadian cialis()

Pingback: Northwest Pharmacy()

Pingback: list of reputable canadian pharmacies()

Pingback: buy cheap clomid uk()

Pingback: highest rated canadian pharmacies()

Pingback: clomid medication()

Pingback: selomns.gonevis.coma-modified-age-structured-sir-model-for-covid-19-type-viruses()

Pingback: stromectol at()

Pingback: ivermectin 200()

Pingback: fwervs.gumroad.com()

Pingback: sasnd0.wixsite.comcialispostimpotent-victims-can-now-cheer-up-try-generic-tadalafil-men-health()

Pingback: https://626106aa4da69.site123.me/blog/new-step-by-step-roadmap-for-tadalafil-5mg()

Pingback: ivermectin and india()

Pingback: viagra without a prescription()

Pingback: generic-cialis-20-mg.yolasite.com()

Pingback: tadalafil over the counter()

Pingback: natural pills for ed()

Pingback: https://hsoybn.estranky.sk/clanky/tadalafil-from-india-vs-brand-cialis---sexual-health.html()

Pingback: skuvsbs.gonevis.comwhen-tadalafil-5mg-competitors-is-good()

Pingback: top ed drugs()

Pingback: hemuyrt.livejournal.com325.html()

Pingback: site373681070.fo.team()

Pingback: sehytv.wordpress.com()

Pingback: mazhor4sezon()

Pingback: online pharmacy()

Pingback: ivermectin 12 mg tablet buy()

Pingback: canadian pharmacies online()

Pingback: kuebser.estranky.skclankysupereasy-methods-to-study-every-part-about-online-medicine-order-discount.html()

Pingback: filmfilmfilmes()

Pingback: kewertyn.wordpress.com20220427expect-more-virtual-house-calls-out-of-your-doctor-thanks-to-telehealth-revolution()

Pingback: https://kerbiss.wordpress.com/2022/04/27/14/()

Pingback: gRh9UPV()

Pingback: https://heswcxc.wordpress.com/2022/04/30/online-medicine-tablets-shopping-promotion-one-hundred-and-one/()

Pingback: ivermectin dose for chickens()

Pingback: https://sernert.estranky.sk/clanky/confidential-information-on-online-pharmacies.html()

Pingback: list of reputable canadian pharmacies()

Pingback: what is the active ingredient in ivermectin()

Pingback: https://626f977eb31c9.site123.me/blog/how-google-is-changing-how-we-approach-online-order-medicine-1()

Pingback: highest rated canadian pharmacies()

Pingback: online-pharmacies0.yolasite.com()

Pingback: Northwest Pharmacy()

Pingback: best canadian pharmacies online()

Pingback: prescriptions from canada without()

Pingback: new erectile dysfunction treatment()

Pingback: https://kerntyas.gonevis.com/the-mafia-guide-to-online-pharmacies/()

Pingback: kerbnt.flazio.com()

Pingback: ivermectin for sale humans()

Pingback: canada pharmacies online()

Pingback: over the counter ed()

Pingback: ime.nucialisonlinei.com()

Pingback: buy viagra 25mg()

Pingback: kerntyast.flazio.com()

Pingback: sekyuna.gonevis.comthree-step-guidelines-for-online-pharmacies()

Pingback: cdc hydroxychloroquine()

Pingback: prescriptions from canada without()

Pingback: 9-05-2022()

Pingback: pharmacy-online.webflow.io()

Pingback: https://canadian-pharmacy.webflow.io/()

Pingback: Canadian Pharmacy USA()

Pingback: canada pharmacy()

Pingback: TopGun2022()

Pingback: https://site561571227.fo.team/()

Pingback: Xvideos()

Pingback: XVIDEOSCOM Videos()

Pingback: https://site102906154.fo.team/()

Pingback: https://hekluy.ucraft.site/()

Pingback: canadian drugs online()

Pingback: ivanesva()

Pingback: canadian pharmacy online()

Pingback: lwerts.livejournal.com276.html()

Pingback: avuiom.sellfy.store()

Pingback: pharmacies.bigcartel.com()

Pingback: northwest pharmacy canada()

Pingback: gewsd.estranky.skclankydrugstore-online.html()

Pingback: kqwsh.wordpress.com20220516what-everybody-else-does-when-it-comes-to-online-pharmacies()

Pingback: canadian rx()

Pingback: canadian pharmaceuticals()

Pingback: mexican pharmacy without prescription()

Pingback: online canadian pharmacy()

Pingback: how to get prescription drugs without doctor()

Pingback: cialis pharmacy()

Pingback: canadian pharmacies without an rx()

Pingback: asebg.bigcartel.comcanadian-pharmacy()

Pingback: https://medicine-online.estranky.sk/clanky/understand-covid-19-and-know-the-tricks-to-avoid-it-from-spreading-----medical-services.html()

Pingback: canadian pharmacycanadian pharmacy()

Pingback: sildenafil tadalafil()

Pingback: https://disvaiza.mystrikingly.com/()

Pingback: canada drugs()

Pingback: https://kewburet.wordpress.com/2022/04/27/how-to-keep-your-workers-healthy-during-covid-19-health-regulations/()

Pingback: generic viagra walmart()

Pingback: kaswesa.nethouse.ru()

Pingback: buy cialis through paypal()

Pingback: 628f789e5ce03.site123.meblogwhat-everybody-else-does-when-it-comes-to-canadian-pharmacies()

Pingback: Netflix()

Pingback: meritroyalbet()

Pingback: Zvezdy-v-Afrike-2-sezon-14-seriya()

Pingback: Krylya-nad-Berlinom()

Pingback: FILM()

Pingback: designchita.ru()

Pingback: YA-krasneyu()

Pingback: design-human.ru()

Pingback: designmsu.ru()

Pingback: vkl-design.ru()

Pingback: irida-design.ru()

Pingback: ivermectin 80 mg()

Pingback: Intimsiti-v-obhod-blokirovok()

Pingback: online canadian pharmacies()

Pingback: canada viagra()

Pingback: psy-()

Pingback: stromectol brand()

Pingback: moskva psiholog online()

Pingback: slovar po psihoanalizu laplansh()

Pingback: psy online()

Pingback: http://pharmacy.prodact.site/()

Pingback: Gz92uNNH()

Pingback: https://hub.docker.com/r/gserv/pharmacies()

Pingback: do-posle-psihologa()

Pingback: uels ukrain()

Pingback: https://hertb.mystrikingly.com/()

Pingback: canada drugs()

Pingback: canadian pharmacy cialis()

Pingback: https://ksorvb.estranky.sk/clanky/why-online-pharmacies-is-good-friend-to-small-business.html()

Pingback: gevcaf.estranky.czclankysafe-canadian-online-pharmacies.html()

Pingback: buy viagra now()

Pingback: https://kwervb.estranky.cz/clanky/canadian-government-approved-pharmacies.html()

Pingback: side effects for ivermectin()

Pingback: bahis siteleri()

Pingback: DPTPtNqS()

Pingback: qQ8KZZE6()

Pingback: D6tuzANh()

Pingback: SHKALA TONOV()

Pingback: Øêàëà òîíîâ()

Pingback: russianmanagement.com()

Pingback: sdtyli.zombeek.cz()

Pingback: https://kwsde.zombeek.cz/()

Pingback: 3Hk12Bl()

Pingback: 3NOZC44()

Pingback: heklrs.wordpress.com20220614canadian-government-approved-pharmacies()

Pingback: 01211()

Pingback: tor-lyubov-i-grom()

Pingback: film-tor-2022()

Pingback: hd-tor-2022()

Pingback: hdorg2.ru()

Pingback: canada online pharmacy()

Pingback: ivermectin 4 tablets price()

Pingback: JXNhGmmt()

Pingback: Psikholog()

Pingback: netstate.ru()

Pingback: https://site955305180.fo.team/()

Pingback: site841934642.fo.team()

Pingback: cost for ivermectin 3mg()

Pingback: pharmacy canada()

Pingback: https://62b2ffff12831.site123.me/blog/canadian-pharmaceuticals-for-usa-sales()

Pingback: tor-lyubov-i-grom.ru()

Pingback: chelovek soznaniye mozg()

Pingback: https://thefencefilm.co.uk/community/profile/hswlux/()

Pingback: order stromectol 6mg()

Pingback: bit.ly()

Pingback: anewearthmovement.orgcommunityprofilemefug()

Pingback: meritking()

Pingback: http://sandbox.autoatlantic.com/community/profile/kawxvb/()

Pingback: lwerfa.iwopop.com()

Pingback: Canadian Pharmacy USA()

Pingback: http://kawerf.iwopop.com/()

Pingback: bucha killings()

Pingback: War in Ukraine()

Pingback: Ukraine news live()

Pingback: The Latest Ukraine News()

Pingback: www.reddit.comuserdotijezocomments9xlg6gonline_pharmacies()

Pingback: my.desktopnexus.comPharmaceuticalsjournalcanadian-pharmaceuticals-for-usa-sales-38346()

Pingback: canadian pharmacies that ship to us()

Pingback: legitimate canadian mail order pharmacies()

Pingback: discount stromectol()

Pingback: https://www.formlets.com/forms/v7CoE3An9poMtRwF/()

Pingback: buy tadalafil pills()

Pingback: online pharmacy()

Pingback: stats()

Pingback: canadian pharmacy world()

Pingback: list of reputable canadian pharmacies()

Pingback: Ukraine-war()

Pingback: movies()

Pingback: gidonline()

Pingback: https://canadianpharmacy.teachable.com/()

Pingback: stromectol 6mg tablet for lice()

Pingback: agrtyh.micro.blog()

Pingback: canadianpharmacy()

Pingback: mir dikogo zapada 4 sezon 4 seriya()

Pingback: www.artstation.compharmacies()

Pingback: web()

Pingback: film.8filmov.ru()

Pingback: https://www.formlets.com/forms/FgIl39avDRuHiBl4/()

Pingback: viagra canada()

Pingback: kaswes.proweb.cz()

Pingback: https://kvqtig.zombeek.cz/()

Pingback: http://kwsedc.iwopop.com/()

Pingback: http://kwerks.iwopop.com/()

Pingback: cialis canadian pharmacy()

Pingback: buy viagra now()

Pingback: gswera.livejournal.com385.html()

Pingback: canadian pharmacys()

Pingback: https://azuvh4.wixsite.com/pharmaceuticals-onli/post/london-drugs-canada()

Pingback: cheap generic cialis()

Pingback: hub.docker.comrpharmaciesonline()

Pingback: canadian discount pharmacies()

Pingback: www.divephotoguide.comuserpharmacies()

Pingback: https://hkwerf.micro.blog/()

Pingback: https://my.desktopnexus.com/Canadian-pharmacies/journal/safe-canadian-online-pharmacies-38571/()

Pingback: https://canadian-government-approved-pharmacies.webflow.io/()

Pingback: lasevs.estranky.czclankypharmaceuticals-online-australia.html()

Pingback: best canadian mail order pharmacies()

Pingback: https://pedrew.zombeek.cz/()

Pingback: cialis cost walmart()

Pingback: https://fermser.flazio.com/()

Pingback: prescription drugs without prior prescription()

Pingback: northwest pharmacies()

Pingback: fofenp.wixsite.comlondon-drugs-canadaenpostpharmacies-shipping-to-usa-that()

Pingback: Anonymous()

Pingback: https://swebas.livejournal.com/359.html()

Pingback: best canadian pharmacies online()

Pingback: https://canadian-pharmacies.webflow.io/()

Pingback: liusia-8-seriiaonlain()

Pingback: https://my.desktopnexus.com/kawemn/journal/pharmaceuticals-online-australia-38678/()

Pingback: www.divephotoguide.comuserdrugs()

Pingback: https://hub.docker.com/r/dkwer/drugs()

Pingback: smotret-polnyj-film-smotret-v-khoroshem-kachestve()

Pingback: form.jotform.comdecotecanadian-pharmacies-shipping-to-the()

Pingback: online drug store()

Pingback: tadalafil over the counter()

Pingback: https://kawers.micro.blog/()

Pingback: filmgoda.ru()

Pingback: rodnoe-kino-ru()

Pingback: buy generic cialis pills()

Pingback: buy cheap cialis no prescription()

Pingback: https://alewrt.flazio.com/()

Pingback: buycialisonline.fo.team()

Pingback: confeitofilm()

Pingback: stat.netstate.ru()

Pingback: https://laswert.wordpress.com/()

Pingback: kasheras.livejournal.com283.html()

Pingback: https://kwxcva.estranky.cz/clanky/cialis-20-mg.html()

Pingback: https://tadalafil20mg.proweb.cz/()

Pingback: https://owzpkg.zombeek.cz/()

Pingback: buy generic cialis()

Pingback: buycialisonline.bigcartel.comcialis-without-a-doctor-prescription()

Pingback: buycialisonline.teachable.com()

Pingback: kalwer.micro.blog()

Pingback: my.desktopnexus.comBuycialisjournalcialis-without-a-doctor-prescription-38780()

Pingback: sY5am()

Pingback: buy cialis without a doctor's prescription()

Pingback: buy cheap cialis on line()

Pingback: https://tadalafil20mg.webflow.io/()

Pingback: buy cialis without a doctor's prescription()

Pingback: buy tadalafil()

Pingback: buy cials online()

Pingback: https://linktr.ee/buycialisonline()

Pingback: telegra.phCialis-20mg-08-13()

Pingback: buy cialis online without a prescription()

Pingback: kwenzx.nethouse.ru()

Pingback: https://dwerks.nethouse.ru/()

Pingback: canadian pharmacies()

Pingback: linktr.eeonlinepharmacies()

Pingback: telegra.phReputable-canadian-pharmaceuticals-online-08-12()

Pingback: graph.orgPharmacies-in-canada-shipping-to-usa-08-12()

Pingback: best canadian pharmacies online()

Pingback: online pharmacies()

Pingback: canada viagra()

Pingback: buy viagra online no prescription()

Pingback: buyviagraonline.estranky.skclankybuy-viagra-without-prescription-pharmacy-online.html()

Pingback: https://buyviagraonline.flazio.com/()

Pingback: buy viagra pills online()

Pingback: Dom drakona()

Pingback: JGXldbkj()

Pingback: aOuSjapt()

Pingback: noyano.wixsite.combuyviagraonline()

Pingback: where to buy viagra online()

Pingback: https://buyviagraonl.livejournal.com/386.html()

Pingback: buy viagra pills()

Pingback: buy viagra uk()

Pingback: buy viagra pills()

Pingback: buy viagra delhi()

Pingback: ìûøëåíèå()

Pingback: psikholog moskva()

Pingback: buy viagra online cheap()

Pingback: A片()

Pingback: pornoizle}()

Pingback: Usik Dzhoshua 2 2022()

Pingback: porno}()

Pingback: buy viagra no rx()

Pingback: buyviagraonline.teachable.com()

Pingback: https://telegra.ph/How-to-get-viagra-without-a-doctor-08-18()

Pingback: https://graph.org/Buying-viagra-without-a-prescription-08-18()

Pingback: Dim Drakona 2022()

Pingback: buy viagra us pharmacy()

Pingback: https://my.desktopnexus.com/buyviagraonline/journal/online-viagra-without-a-prescriptuon-38932/()

Pingback: https://www.divephotoguide.com/user/buyviagraonline()

Pingback: buy generic viagra()

Pingback: viagrawithoutprescription.webflow.io()

Pingback: TwnE4zl6()

Pingback: form.jotform.com222341315941044()

Pingback: https://linktr.ee/buyviagraonline()

Pingback: buy cheap viagra no prescription()

Pingback: discount canadian pharmacies()

Pingback: psy 3CtwvjS()

Pingback: https://onlineviagra.mystrikingly.com/()

Pingback: where to buy viagra online()

Pingback: https://viagraonline.estranky.sk/clanky/viagra-without-prescription.html()

Pingback: lalochesia()

Pingback: https://viagraonlineee.wordpress.com/()

Pingback: https://viagraonline.home.blog/()

Pingback: viagraonlinee.livejournal.com492.html()

Pingback: https://onlineviagra.flazio.com/()

Pingback: onlineviagra.fo.team()

Pingback: canada online pharmacy()

Pingback: canadian viagra()

Pingback: https://disqus.com/home/forum/canadian-pharmaceuticals-online/()

Pingback: canadian prescriptions online()

Pingback: film onlinee()

Pingback: discount canadian pharmacies()

Pingback: programma peredach na segodnya()

Pingback: https://challonge.com/en/canadianpharmaceuticalsonlinemt()

Pingback: 500px.complistofcanadianpharmaceuticalsonline()

Pingback: https://www.seje.gov.mz/question/canadian-pharmacies-shipping-to-usa/()

Pingback: challonge.comencanadianpharmaciesshippingtousa()

Pingback: challonge.comencanadianpharmaceuticalsonlinetousa()

Pingback: pinshape.comusers2441403-canadian-pharmaceuticals-online()

Pingback: canada drug pharmacy()

Pingback: online pharmacies()

Pingback: pinshape.com/users/2441621-canadian-pharmaceutical-companies()

Pingback: pinshape.comusers2441621-canadian-pharmaceutical-companies()

Pingback: reallygoodemails.comcanadianpharmaceuticalcompanies()

Pingback: pinshape.comusers2445987-order-stromectol-over-the-counter()

Pingback: reallygoodemails.comorderstromectoloverthecounter()

Pingback: https://challonge.com/en/orderstromectoloverthecounter()

Pingback: https://500px.com/p/orderstromectoloverthecounter()

Pingback: psycholog-v-moskve.ru()

Pingback: psycholog-moskva.ru()

Pingback: www.seje.gov.mzquestionorder-stromectol-over-the-counter-6()

Pingback: order stromectol over the counter()

Pingback: https://canadajobscenter.com/author/canadianpharmaceuticalsonline/()

Pingback: canadian prescription drugstore()

Pingback: https://canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.bandcamp.com/releases()

Pingback: https://ktqt.ftu.edu.vn/en/question list/canadian-pharmaceuticals-for-usa-sales/()

Pingback: https://www.provenexpert.com/canadian-pharmaceuticals-online/()

Pingback: where to buy stromectol uk()

Pingback: 3qAIwwN()

Pingback: mgfmail()

Pingback: https://ktqt.ftu.edu.vn/en/question list/order-stromectol-over-the-counter-10/()

Pingback: orderstromectoloverthecounter.bandcamp.comreleases()

Pingback: discount stromectol()

Pingback: www.repairanswers.netquestionorder-stromectol-over-the-counter-2()

Pingback: video-2()

Pingback: www.repairanswers.netquestionstromectol-order-online()

Pingback: https://canadajobscenter.com/author/arpreparof1989/()

Pingback: sezons.store()

Pingback: https://aoc.stamford.edu/profile/goatunmantmen/()

Pingback: https://web904.com/stromectol-buy/()

Pingback: socionika-eniostyle.ru()

Pingback: https://web904.com/buy-ivermectin-online-fitndance/()

Pingback: stromectol for sale()

Pingback: canadajobscenter.comauthorereswasint()

Pingback: canada pharmacies online prescriptions()

Pingback: canadian medications()

Pingback: https://pinshape.com/users/2461310-canadian-pharmacies-shipping-to-usa()

Pingback: pinshape.comusers2462760-order-stromectol-over-the-counter()

Pingback: https://pinshape.com/users/2462910-order-stromectol-online()

Pingback: 500px.com/p/phraspilliti()

Pingback: 000-1()

Pingback: 3SoTS32()

Pingback: 3DGofO7()

Pingback: https://web904.com/canadian-pharmaceuticals-for-usa-sales/()

Pingback: 500px.compskulogovid?view=groups()

Pingback: canadian cialis()

Pingback: https://reallygoodemails.com/canadianpharmaceuticalsonlineusa()

Pingback: cialis canadian pharmacy()

Pingback: https://sanangelolive.com/members/pharmaceuticals()

Pingback: canadian drugstore()

Pingback: https://haikudeck.com/canadian-pharmaceuticals-online-personal-presentation-827506e003()

Pingback: buyersguide.americanbar.orgprofile4206420()

Pingback: Canadian Pharmacies Shipping to USA()

Pingback: slides.comcanadianpharmaceuticalsonline()

Pingback: https://challonge.com/esapenti()

Pingback: challonge.comgotsembpertvil()

Pingback: https://challonge.com/citlitigolf()

Pingback: buy generic stromectol()

Pingback: ivermectin()

Pingback: lehyriwor.estranky.skclankystromectol-cream.html()

Pingback: https://dsdgbvda.zombeek.cz/()

Pingback: stromectol medication()

Pingback: wwwi.odnoklassniki-film.ru()

Pingback: https://www.myscrsdirectory.com/profile/421708/0()

Pingback: supplier.ihrsa.orgprofile4217170()

Pingback: most reliable canadian pharmacies()

Pingback: canadian pharmacies online prescriptions()

Pingback: moaamein.nacda.comprofile4220180()

Pingback: www.audiologysolutionsnetwork.orgprofile4220190()

Pingback: network.myscrs.orgprofile4220200()

Pingback: https://sanangelolive.com/members/canadianpharmaceuticalsonlineusa()

Pingback: sanangelolive.commembersgirsagerea()

Pingback: www.ecosia.orgsearch?q="My Canadian Pharmacy - Extensive Assortment of Medications – 2022"()

Pingback: https://www.mojomarketplace.com/user/Canadianpharmaceuticalsonline-EkugcJDMYH()

Pingback: canadian pharmacies online()

Pingback: www.giantbomb.comprofilecanadapharmacyblogcanadian-pharmaceuticals-online265652()

Pingback: https://feeds.feedburner.com/bing/Canadian-pharmaceuticals-online()

Pingback: does hydroxychloroquine work()

Pingback: search.gmx.comwebresult?q="My Canadian Pharmacy - Extensive Assortment of Medications – 2022"()

Pingback: rftrip.ru()

Pingback: search.seznam.cz?q="My Canadian Pharmacy - Extensive Assortment of Medications – 2022"()

Pingback: buy generic stromectol()

Pingback: canadian pharmacy viagra brand()

Pingback: madridbet()

Pingback: swisscows.comenweb?query="My Canadian Pharmacy - Extensive Assortment of Medications – 2022"()

Pingback: www.dogpile.comserp?q="My Canadian Pharmacy - Extensive Assortment of Medications – 2022"()

Pingback: online pharmacies()

Pingback: search.givewater.comserp?q="My Canadian Pharmacy - Extensive Assortment of Medications – 2022"()

Pingback: canadian pharmacies shipping to usa()

Pingback: https://www.qwant.com/?q="My Canadian Pharmacy - Extensive Assortment of Medications – 2022"()

Pingback: https://results.excite.com/serp?q="My Canadian Pharmacy - Extensive Assortment of Medications – 2022"()

Pingback: www.infospace.comserp?q="My Canadian Pharmacy - Extensive Assortment of Medications – 2022"()

Pingback: dolpsy.ru()

Pingback: headwayapp.cocanadianppharmacy-changelog()

Pingback: https://results.excite.com/serp?q="My Canadian Pharmacy - Extensive Assortment of Medications – 2022"()

Pingback: canadian pharmacies online prescriptions()

Pingback: hydroxychloroquine for sale()

Pingback: https://feeds.feedburner.com/bing/stromectolnoprescription()

Pingback: https://reallygoodemails.com/orderstromectoloverthecounterusa()

Pingback: kin0shki.ru()

Pingback: https://aoc.stamford.edu/profile/cliclecnotes/()

Pingback: 3o9cpydyue4s8.ru()

Pingback: pinshape.comusers2491694-buy-stromectol-fitndance()

Pingback: www.provenexpert.commedicament-stromectol()

Pingback: mb588.ru()

Pingback: stromectol pill()

Pingback: stromectol for sale online()

Pingback: history-of-ukraine.ru news ukraine()

Pingback: buy stromectol uk()

Pingback: newsukraine.ru()

Pingback: list of reputable canadian pharmacies()

Pingback: what is stromectol()

Pingback: stromectol order()

Pingback: online canadian pharmacy()

Pingback: edu-design.ru()

Pingback: tftl.ru()

Pingback: www.infospace.comserp?q="My Canadian Pharmacy - Extensive Assortment of Medications – 2022"()

Pingback: buy viagra now()

Pingback: buy ivermectin online fitndance()

Pingback: orderstromectoloverthecounter.mystrikingly.com()

Pingback: https://stromectoloverthecounter.wordpress.com/()

Pingback: buystromectol.livejournal.com421.html()

Pingback: order stromectol over the counter()

Pingback: https://search.lycos.com/web/?q="My Canadian Pharmacy - Extensive Assortment of Medications – 2022"()

Pingback: canadian prescription drugstore()

Pingback: stromectol overdose()

Pingback: graph.orgOrder-Stromectol-over-the-counter-10-29-2()

Pingback: brutv()

Pingback: orderstromectoloverthecounter.fo.team()

Pingback: https://orderstromectoloverthecounter.proweb.cz/()

Pingback: orderstromectoloverthecounter.nethouse.ru()

Pingback: https://sandbox.zenodo.org/communities/canadianpharmaceuticalsonline/()

Pingback: https://demo.socialengine.com/blogs/2403/1227/canadian-pharmaceuticals-online()

Pingback: site 2023()

Pingback: https://pharmaceuticals.cgsociety.org/jvcc/canadian-pharmaceuti()

Pingback: buy propecia 84()

Pingback: how to buy cheap propecia()

Pingback: online drug store()

Pingback: trust pharmacy canada()

Pingback: https://www.dibiz.com/ndeapq()

Pingback: grandpashabet()

Pingback: www.podcasts.comcanadian-pharmacies-shipping-to-usa()

Pingback: https://canadianpharmaceuticals.educatorpages.com/pages/canadian-pharmacies-shipping-to-usa()

Pingback: canadian pharmacies that ship to us()

Pingback: https://peatix.com/user/14373921/view()

Pingback: www.cakeresume.commebest-canadian-pharmaceuticals-online()

Pingback: dragonballwiki.netforumcanadian-pharmaceuticals-online-safe()

Pingback: the-dots.comprojectscovid-19-in-seven-little-words-848643()

Pingback: jemi.socanadian-pharmacies-shipping-to-usa()

Pingback: canadian online pharmacies()

Pingback: https://medium.com/@pharmaceuticalsonline/canadian-pharmaceutical-drugstore-2503e21730a5()

Pingback: infogram.comcanadian-pharmacies-shipping-to-usa-1h1749v1jry1q6z()

Pingback: pinshape.comusers2507399-best-canadian-pharmaceuticals-online()

Pingback: canada drugs()

Pingback: 500px.compmaybenseiprep?view=groups()

Pingback: canadian pharmacies that ship to us()

Pingback: sacajegi.estranky.czclankyonline-medicine-shopping.html()

Pingback: speedopoflet.estranky.skclankyinternational-pharmacy.html()

Pingback: https://dustpontisrhos.zombeek.cz/()

Pingback: https://sanangelolive.com/members/maiworkgendty()

Pingback: issuu.comlustgavalar()

Pingback: calendly.comcanadianpharmaceuticalsonlineonlinepharmacy()

Pingback: https://aoc.stamford.edu/profile/uxertodo/()

Pingback: https://www.wattpad.com/user/Canadianpharmacy()

Pingback: Canadian Pharmacies Shipping to USA()

Pingback: sitestats01()

Pingback: 1c789.ru()

Pingback: cttdu.ru()

Pingback: 500px.compreisupvertketk?view=groups()

Pingback: canadianpharmacy()

Pingback: challonge.comebocivid()

Pingback: https://obsusilli.zombeek.cz/()

Pingback: canadian pharmacy uk delivery()

Pingback: canadian pharcharmy online()

Pingback: canada online pharmacies()

Pingback: canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.tawk.helparticlecanadian-pharmacies-shipping-to-usa()

Pingback: prescription drugs without prior prescription()

Pingback: canada pharmacies()

Pingback: https://suppdentcanchurch.estranky.cz/clanky/online-medicine-order-discount.html()

Pingback: northwest pharmacy canada()

Pingback: https://pinshape.com/users/2513487-online-medicine-shopping()

Pingback: 1703()

Pingback: hdserial2023.ru()

Pingback: https://500px.com/p/meyvancohurt/?view=groups()

Pingback: cialis coupon discounts()

Pingback: serialhd2023.ru()

Pingback: canada online pharmacy()

Pingback: where to buy it stores cenforce 100()

Pingback: matchonline2022.ru()

Pingback: appieloku.estranky.czclankyonline-medicine-to-buy.html()

Pingback: canadian pharmacys()

Pingback: brujagflysban.zombeek.cz()

Pingback: What is intimacy to a woman and kamagra oral jelly in australia?()

Pingback: Does caffeine help quit smoking how much is wellbutrin in canada?()

Pingback: 500px.compstofovinin?view=groups()

Pingback: www.provenexpert.combest-erectile-pills()

Pingback: bit.ly/3OEzOZR()

Pingback: bit.ly/3gGFqGq()

Pingback: bit.ly/3ARFdXA()

Pingback: erectile dysfunction remedies()

Pingback: bit.ly/3ig2UT5()

Pingback: bit.ly/3GQNK0J()

Pingback: Are protein shakes good for weight loss and diet supplements that work?()

Pingback: best erectile dysfunction pills()

Pingback: solutions to erectile dysfunction()

Pingback: erectile dysfunction pills()

Pingback: grandpashabet()

Pingback: How do you love your partner in bed sildenafil soft gel capsule?()

Pingback: https://www.cakeresume.com/me/canadian-pharmaceuticals-online/()

Pingback: bep5w0Df()

Pingback: canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.studio.site()

Pingback: canadian pharmacys()

Pingback: buy viagra now()

Pingback: www()

Pingback: https://canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.blog.jp/archives/19372004.html()

Pingback: canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.doorblog.jparchives19385382.html()

Pingback: What to say to impress a girl buy viagra pills?()

Pingback: https://canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.ldblog.jp/archives/19386301.html()

Pingback: canadian pharmacycanadian pharmacy()

Pingback: canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.publog.jparchives16846649.html()

Pingback: canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.livedoor.bizarchives17957096.html()

Pingback: icf()

Pingback: 24hours-news()

Pingback: rusnewsweek()

Pingback: uluro-ado()

Pingback: online pharmacy canada()

Pingback: https://canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.weblog.to/archives/19410199.html()

Pingback: https://canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.bloggeek.jp/archives/16871680.html()

Pingback: https://canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.blogism.jp/archives/17866152.html()

Pingback: canadian pharmacy world()

Pingback: https://canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.blogto.jp/archives/19498043.html()

Pingback: canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.gger.jparchives18015248.html()

Pingback: Medication information for patients. Cautions dutasteride dosage?()

Pingback: irannews.ru()

Pingback: klondayk2022()

Pingback: canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.golog.jparchives16914921.html()

Pingback: https://canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.liblo.jp/archives/19549081.html()

Pingback: discount canadian pharmacies()

Pingback: https://canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.mynikki.jp/archives/16957846.html()

Pingback: pinshape.comusers2528098-canadian-pharmacy-online()

Pingback: Drugs prescribing information. Generic Name. paxil for anxiety?()

Pingback: canadian pharmacy online()

Pingback: most reliable canadian pharmacies()

Pingback: canadian pharmacies shipping to usa()

Pingback: https://graph.org/Canadian-pharmacies-online-12-11()

Pingback: canadianonlinepharmacieslegitimate.flazio.com()

Pingback: canadian cialis()

Pingback: online canadian pharmacy()

Pingback: canadian pharmacies online()