Do you stand up for what you believe, regardless of the cost?

In 1940, Air Chief Marshall Hugh Dowding did, and he’s the reason, despite Tobruk and Normandy, despite the Band of Brothers and the Red Army, that we do not speak German today.

Dowding wasn’t your typical war hero. He was quiet, shy, and reserved. His colleagues nicknamed him “Stuffy,” and the name stuck. But Dowding was also a thoughtful and intelligent man. He was an unconventional thinker. And he was driven by intense courage and integrity. That integrity drove him to stand up for what he believed in.

When Dowding was made head of Fighter Command in 1936 his squadrons were equipped with weapons like the Gloster Gladiator. It was the pinnacle of World War I technology. A slow and poorly armed biplane. It did not stand a chance against the modern fighter aircraft the Germans were deploying in massive numbers.

The problem was the conventional wisdom that fighters were useless. After the last war, with Zeppelins setting London ablaze, most people thought that in the next air war bombers would be unstoppable. They thought that Dowding’s defensive fighters wouldn’t stand a chance. So the RAF leadership diverted scarce resources into offensive bomber aircraft.

But Dowding was an unconventional thinker. He did not believe that the “bomber would always get through.” He knew that he needed to modernize his planes. After the Munich crisis in 1938, her knew war was coming and that he had to modernize quickly. But he found himself in constant disagreement with his superiors for the resources to do it. Nonetheless, he stood up for his command and he begged, borrowed, stole, cajoled. And in a few short years he was able to replace planes like the Gladiator with the Hurricane and the world famous Spitfire.

The sleek, fast, heavily armed planes that, even today, are the epitome of fighter aircraft. And the only aircraft in the world that was a match for the Luftwaffe. But because of the resistance he faced building these planes, Dowding did not have enough when war was declared. And this led to an even larger problem.

In May of 1940, while the British were still fighting in France, the RAF ordered Dowding’s precious Hurricanes to France to assist the Allied effort. This distressed him because the French and British were already overwhelmed by the Germans. The Hurricane squadrons were decimated. In 5 days, Dowding lost 25% of his air force. The desperate French president begged the British to send more Hurricanes into the fight. He personally requested 10 more squadrons from Winston Churchill. Dowding knew that if this happened, there would not be enough Fighters to defend England.

So he did something brave, but very unconventional. He asked for a direct meeting with Winston Churchill.

Dowding asked to attend the War Cabinet meeting. This was an unheard of breach of decorum. These were for cabinet leaders and he was much too low on the chain of command to attend. But Dowding felt that he was the only one that could be trusted to plead his case. Luckily, his request was granted, and on May 15th 1940, he found himself in the War Cabinet Meeting Room. Filling the room was a long table covered in green felt. Sitting in the center was the unmistakable frown of Churchill himself. Dowding’s two superiors, Chief of Air Staff Sir Cyril Newall and Secretary of State for Air Archibald Sinclair were already seated at the table. Dowding didn’t merit a seat at the table, so they put him in a chair against the wall. He sat there waiting until it was time to discuss sending the fighters to France.

At the heart of the issue was Churchill. He was an emotional man and a Francophile who couldn’t imagine Paris falling into German hands. He also had a strategy to fight the Germans on the continent, not over England. These motives drove his decision making and despite the risk, he was insistent that more fighters would go to France.

Dowding stated his case forcefully but Churchill wouldn’t budge. Dowding looked to his bosses, Newall and Sinclair, who he knew agreed with him, for support. Bur sensing Churchill’s mood and not wanting to endanger their own careers, they remained silent.

Finally, in exasperation, he threw down his pen. The room grew silent. Everyone thought he was going to resign. But Dowding was a man of integrity. He knew that he was the best man for the job. So he didn’t resign. He got up, walked around the table, and stood behind Churchill’s chair. Tension hung in the air. He reached over Churchill’s shoulder and placed a graph on the table in front of him.

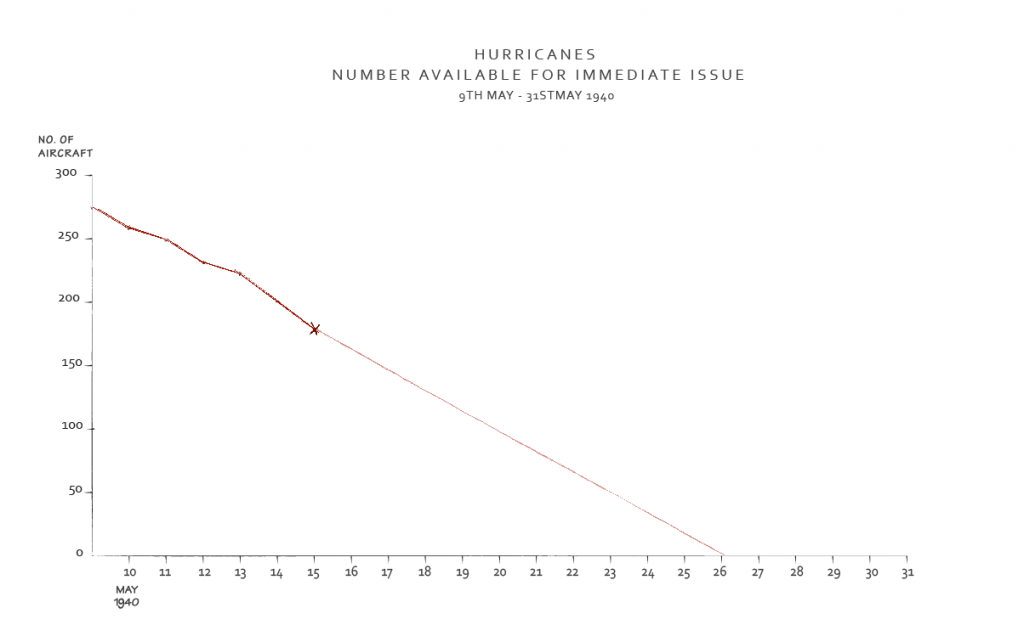

it was a simple graph with a thin red line. It showed the number of Hurricanes Dowding had available. The line sloped to the lower right, showing the losses in the 5 days up to the meeting. It then projected losses in the future at the current rate. By the end of May, that line crossed zero.

Churchill glared at it, frowning. Breaking the silence, Dowding calmly said,

“If the present rate of wastage continues for another fortnight, we shall have not a single Hurricane left in France, or in this country.”

Dowding walked back and took his seat. And Churchill changed his mind. No more fighters would be sent to France.

The confrontation saved England. Three weeks later, when France surrendered, Dowding’s meagre fighter force was all that stood between England and a German invasion. When asked about it years later, Dowding stated that he knew he hadn’t made Churchill a friend. He’d forced him to change his stubborn mind, in front of his cabinet. He expected to return to his command and find a letter telling him he was through. Dowding was prepared to sacrifice his career for the greater good. Thankfully, Churchill kept him on. Dowding wasn’t finished…yet.

Action This Day

So how often as managers and leaders have we been in a situation like this? Where doing the right thing means putting ourselves at risk? And when we are in these situations, how many of us have the integrity to stand up for what we believe? How often do we see ourselves as Dowding but sit silently like Newall and Seward?

I can think of several times in my career when I did not stand up. Where I sat quietly and let my own instinct for self-preservation prevail. Was I really leading with integrity? Did it change the way my employees perceived me? If so, how did that change my effectiveness as a leader?

Now I try and remember Dowding when faced with these situations. Of course, doing the right thing does not ultimately mean you’ll come out on top. But having integrity as a leader is having the courage to stand up for what you think is right, when you have the most to lose.

This is just one lesson from this story. There are other lessons. Even if we know the importance of having integrity, how do we approach it? How do we effectively stand up and succeed? How do we actually change minds?

Here are a few other things I see:

- Dowding went right to the man who made the final decision. He made his viewpoint known to his bosses, but when it was on the line he pleaded his case to Churchill. Even when that meant stepping outside tradition.

- He also did not trust his superiors to make his case (and rightly so), believing that he was the best person for making his argument.

- When it came to the mechanics of his argument, he was a model of simplicity. He did not argue emotion. His position was cold hard fact. It was impossible for Churchill to defend his emotional stance against that.

- His argument was also simple. It wasn’t a position paper, a root cause analysis, or a PowerPoint. It was simple red line. Simple, yet profound.

In the Comments, tell me what you think.

I don’t think we stand up for what we believe in as much as we should. And I think that hurts our projects, our organizations, and teams. Prove me wrong. Tell me when about a time you did or didn’t stand up for what you believe in. Why or why not? How did it affect you as a leader?

Pingback: Google()

Pingback: fetish fantasy door swing()

Pingback: prostate vibrator()

Pingback: remote control underwear()

Pingback: how to massage g spot()

Pingback: Koinonia Messages()

Pingback: restaurant menu prices()

Pingback: latest celebrity gossip in nigeria()

Pingback: walmartone wire login()

Pingback: Naija()

Pingback: double dildo()

Pingback: diabetes surgery()

Pingback: dog trainer()

Pingback: SSNI 668()

Pingback: terjemahan()

Pingback: BANNED VIAGRA()

Pingback: test for legionella()

Pingback: 우리카지노()

Pingback: 코인카지노()

Pingback: 예스카지노()

Pingback: wireless bullet vibe()

Pingback: veporn()

Pingback: comprar aceite de cbd()

Pingback: 우리카지노()

Pingback: 더킹카지노()

Pingback: 코인카지노()

Pingback: CCRMG()

Pingback: ETORRENT DOWNLOAD PORN()

Pingback: most realistic dildo()

Pingback: silicone glans ring()

Pingback: https://images.google.kg/url?q=httpsphongkhamhana.com()

Pingback: free sexy()

Pingback: Roadside assistance()

Pingback: FCMB BANK()

Pingback: Google()

Pingback: anal sex toy()

Pingback: best clit massager()

Pingback: quickshot stroker()

Pingback: DRUGS()

Pingback: CHEAP VIAGRA()

Pingback: Fantasy Play()

Pingback: water based anal lubricant()

Pingback: online lingerie()

Pingback: extreme fisting()

Pingback: vector art service()

Pingback: https://www.isaacroyston.com/()

Pingback: best rc plane transmitter()

Pingback: ketamine()

Pingback: Punch Newspaper()

Pingback: Buy real weed online()

Pingback: online research library()

Pingback: order Adderall online legally()

Pingback: supreme dab cartridges()

Pingback: powerful massager()

Pingback: adam and eve magic wand()

Pingback: vibrating strapon dildo()

Pingback: فیلم سکسی ایرانی()

Pingback: digital marketing agency in navi mumbai()

Pingback: mygiftcardsite()

Pingback: chinese food delivery near me()

Pingback: www.myaccountaccess.com()

Pingback: netprobk()

Pingback: best cbd oil for pain()

Pingback: best cbd oil for anxiety()

Pingback: best cbd capsules()

Pingback: nekomu berezu zalomati tekst()

Pingback: inflatable stand up paddle board()

Pingback: Age()

Pingback: enamelware()

Pingback: VIAgRA()

Pingback: Zügelauto()

Pingback: https://cryptocurrencyinafrica.site/()

Pingback: https://cryptocurrencyafrica.icu/()

Pingback: hotmail login()

Pingback: پورن ایرانی()

Pingback: bullet sex toy()

Pingback: science experiments for kids()

Pingback: best cbd gummies()

Pingback: University()

Pingback: Anambra News()

Pingback: Download songs()

Pingback: sex toys()

Pingback: pc apps for windows 10()

Pingback: free download for pc windows()

Pingback: apps download for windows 10()

Pingback: free download for windows 8()

Pingback: free download for windows 10()

Pingback: sous traitance web()

Pingback: free app download()

Pingback: apk for pc download()

Pingback: realistic dildo()

Pingback: sous traitance web()

Pingback: sloth at st louis aquarium()

Pingback: best cbd oil for pain()

Pingback: cbd oil for sale()

Pingback: best cbd oil for depression()

Pingback: best cbd oil for pain()

Pingback: https://cleaningserviceofdc.com()

Pingback: liquid red mercury()

Pingback: island invest()

Pingback: THE CAMERA GUYS()

Pingback: cock sleeve()

Pingback: thick dildo()

Pingback: web design warrington()

Pingback: Water Softener System()

Pingback: alabama hot pocket()

Pingback: "cialis"()

Pingback: do pheromones perfumes work()

Pingback: Free Ads UK()

Pingback: cheap Viagra()

Pingback: xnxx()

Pingback: best cbd()

Pingback: Vape juice()

Pingback: rotating vibrator()

Pingback: Xanax()

Pingback: design container home online()

Pingback: Daftar Bandar Poker()

Pingback: apple headquarters()

Pingback: pakistani wedding dresses()

Pingback: couples sex toys()

Pingback: Szkolenie okresowe z zakresu bhp i ppoz dla pracownikow inzynieryjno technicznych()

Pingback: viagra()

Pingback: viagra()

Pingback: best cannabidiol oil for pain()

Pingback: cannabidiol()

Pingback: Buy marijuana online()

Pingback: Vape Shops Near Me()

Pingback: THC Oil()

Pingback: Pound of Weed()

Pingback: reshp porn()

Pingback: Vaishali()

Pingback: Joel Osteen 2020()

Pingback: google maps seo services()

Pingback: agence digitale paris()

Pingback: cannabidiol gummies()

Pingback: cbd shop()

Pingback: cbd()

Pingback: работа водитель в США()

Pingback: menards employee login()

Pingback: SEO()

Pingback: fda us agent()

Pingback: Professional logo design()

Pingback: buy instagram followers()

Pingback: sex toys()

Pingback: Flooring in Miami()

Pingback: Smoke shops()

Pingback: smm panel hero()

Pingback: tech devices()

Pingback: indian visa()

Pingback: Buy online legally()

Pingback: Toronto Web Designer()

Pingback: selling a mobile home()

Pingback: best CBD oils()

Pingback: Robux Generator()

Pingback: pet life today()

Pingback: gk quiz()

Pingback: cbd oil near me()

Pingback: deluxe rabbit()

Pingback: http://bbs.ffsky.com/home.php?mod=space&uid=4867453&do=profile&from=space()

Pingback: how to use cock rings()

Pingback: Order ativan online legally()

Pingback: Order tramadol online()

Pingback: best CBD oil for depression()

Pingback: Order oxycodone online()

Pingback: https://newshush.com/digital-marketing-agency-2020-308()

Pingback: russian samovar()

Pingback: Order ambien online()

Pingback: kitesurfing sri lanka()

Pingback: how to order drivers license online()

Pingback: pornographie()

Pingback: Vape Shops Near Me()

Pingback: situs bandar poker()

Pingback: site:https://seovalor.com()

Pingback: Buy ambien frkm Canada()

Pingback: clones for sale()

Pingback: pleasure beads()

Pingback: hasta yatağı()

Pingback: http://boise.businesslistus.com/business/5213557.htm()

Pingback: http://www.looklocally.com/united-states/boise/home-services/mold-removal-boise()

Pingback: electrical panel upgrade()

Pingback: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BaW5J959xzg&t=1s()

Pingback: cbd oil for dogs()

Pingback: Buy Cannabis Oil Online()

Pingback: Logo()

Pingback: Sleep apnea()

Pingback: http://astrabios.ru/forum/?PAGE_NAME=profile_view&UID=59871()

Pingback: http://mediajx.com/story7450794/vespa-custom()

Pingback: tulpentour()

Pingback: vape shop in uk()

Pingback: self-improvement()

Pingback: http://prohouseworks.com/2020/01/28/how-to-manage-your-lawn-in-antioch-ca/()

Pingback: strongest CBD()

Pingback: CBD oil 500()

Pingback: CBD gummies 10mg()

Pingback: huge dildos()

Pingback: CBD near me()

Pingback: http://medford.bizlistusa.com/business/5211391.htm()

Pingback: niagara fall tour()

Pingback: pc app free download()

Pingback: apk for windows 7 download()

Pingback: dildo harness()

Pingback: vibrating panties with remote()

Pingback: app apk for pc()

Pingback: apps download for windows 7()

Pingback: free app for pclaptop app free download()

Pingback: free download for windows 7()

Pingback: http://milotmbna.develop-blog.com/400031/a-simple-key-for-carpet-cleaning-companies-unveiled()

Pingback: https://superfastmoney.org/()

Pingback: How have multiple orgasms()

Pingback: Top Of The Range Cafe()

Pingback: http://www.the-nextlevel.com/tnl/members/40366-waterheater01?vmid=22239#vmessage22239()

Pingback: dildo for beginners()

Pingback: CBD oil()

Pingback: bondage sex toys()

Pingback: bars with games atlanta()

Pingback: best smart product()

Pingback: Recreation Tipsy()

Pingback: united tours israel()

Pingback: webehigh()

Pingback: CBD products()

Pingback: https://diamondcleaningusa.com/why-having-sex-in-a-clean-room-is-better/()

Pingback: massive dildo()

Pingback: onhax me()

Pingback: how to make sex toy()

Pingback: Carpet Cleaning Maple Ridge()

Pingback: داستان سکسی()

Pingback: Online Advertising()

Pingback: Las Vegas Homes for Sale Las Vegas Real Estate LVR()

Pingback: free download()

Pingback: travel()

Pingback: https://myinforms.com/()

Pingback: CBD oil near me()

Pingback: suction cup dong()

Pingback: cbd oil for fibromyalgia()

Pingback: cbd and blood pressure()

Pingback: royal cbd()

Pingback: dildo()

Pingback: Buy Quality Backlinks()

Pingback: https://mksorb.com/adguard-premium-apk/()

Pingback: Buy Quality Backlinks Cheap()

Pingback: https://5starlegitdocuments.com/counterfeit-money/()

Pingback: https://mksorb.com/youcam-perfect-selfie-photo-editor/()

Pingback: https://mksorb.com/avee-music-player-pro-apk/()

Pingback: MILF porn()

Pingback: Carpet Cleaning Specials()

Pingback: remote underwear()

Pingback: Apostle Joshua Selman Sermons()

Pingback: https://mksorb.com/aio-launcher-pro-apk/()

Pingback: Net Worth()

Pingback: https://mksorb.com/photogrid-apk/()

Pingback: rabbit vibrator review()

Pingback: thrusting()

Pingback: https://mksorb.com/dream-league-soccer-2019-apk/()

Pingback: căn hộ hưng thịnh()

Pingback: https://mksorb.com/1password-pro-apk/()

Pingback: Move-out()

Pingback: развитие речи ребенка от года()

Pingback: salary 15000 per month personal loan()

Pingback: Stiiizy()

Pingback: https://www.fbioyf.unr.edu.ar/evirtual/blog/index.php?entryid=97800()

Pingback: Liiit Stiiizy()

Pingback: New Carlisle Indiana()

Pingback: https://mksorb.com/arc-launcher-pro-apk/()

Pingback: cannabis for the culture()

Pingback: mind research & development()

Pingback: hightech sex toys()

Pingback: mind research & development()

Pingback: stiiizy()

Pingback: usa visa card()

Pingback: https://mksorb.com/go-sms-pro-keyboard-apk/()

Pingback: https://mksorb.com/smule-vip-apk/()

Pingback: dax history()

Pingback: https://mksorb.com/hill-climb-racing-2-mod-apk/()

Pingback: sex livestreami()

Pingback: MKsOrb.Com()

Pingback: MKsOrb()

Pingback: MKsOrb()

Pingback: pl/sql diagram()

Pingback: MKsOrb.Com()

Pingback: MKsOrb.Com()

Pingback: Maid Las Vegas()

Pingback: MKsOrb()

Pingback: bàn học chống gù chống cận thị()

Pingback: sexy live cams()

Pingback: nude()

Pingback: sex()

Pingback: MKsOrb()

Pingback: CBD gummies()

Pingback: MKsOrb.Com()

Pingback: MKsOrb.Com()

Pingback: Best Link Shortener()

Pingback: Free Download()

Pingback: MKsOrb()

Pingback: THC VAPE OIL()

Pingback: Android()

Pingback: MKsOrb()

Pingback: Pro()

Pingback: https://royalcbd.com/product/cbd-capsules-25mg/()

Pingback: Wooden Floors()

Pingback: https://royalcbd.com/product/cbd-salve/()

Pingback: https://royalcbd.com/product/cbd-gummies-25mg/()

Pingback: Visit()

Pingback: best CBD oil()

Pingback: have a peek here()

Pingback: Coinpunk()

Pingback: Click This Link()

Pingback: coinchomp()

Pingback: have a peek at this website()

Pingback: MKsOrb()

Pingback: adam and eve dildo()

Pingback: سکس باحال زن و شوهر ايراني()

Pingback: MKsOrb()

Pingback: داستان سکسی()

Pingback: MKsOrb.Com()

Pingback: adoptable dogs near me()

Pingback: MKsOrb.Com()

Pingback: THC vape juice()

Pingback: Pet stores()

Pingback: MKsOrb()

Pingback: Dank cartridges()

Pingback: safestore auto()

Pingback: MKsOrb()

Pingback: MKsOrb()

Pingback: MKsOrb.Com()

Pingback: THC vape juice()

Pingback: Pembroke welsh corgi puppies for sale()

Pingback: blue applehead chihuahua puppies for sale()

Pingback: french bulldog puppies for sale near me()

Pingback: http://buycounterfeitmoneyonline.net()

Pingback: Dank carts()

Pingback: Puppies for sale()

Pingback: cheap rottweiler puppies for sale()

Pingback: bullmastiff puppy()

Pingback: border collie lab mix puppies for sale()

Pingback: black german shepherd puppies for sale()

Pingback: web design agency()

Pingback: Dank cartridges()

Pingback: Buy weed online()

Pingback: snapdeal lucky draw offer()

Pingback: Buy cannabis online()

Pingback: https://counterfeitmoneyforsale.online/()

Pingback: penis enlargement pump()

Pingback: https://www.gayweddingideas.net/activity/p/636014/()

Pingback: oneplus 8()

Pingback: CBD()

Pingback: CBD()

Pingback: MKsOrb.Com()

Pingback: CBD()

Pingback: CBD()

Pingback: CBD()

Pingback: CBD()

Pingback: CBD()

Pingback: CBD()

Pingback: CBD()

Pingback: how to use strapon()

Pingback: how to file a complaint()

Pingback: buy CBD oil()

Pingback: buy CBD oil()

Pingback: CBD oil()

Pingback: best CBD oil()

Pingback: best CBD oil()

Pingback: buy CBD oil()

Pingback: CBD oil for sale()

Pingback: buy CBD oil()

Pingback: CBD oil for sale()

Pingback: CBD oil()

Pingback: https://freereviewnow.com/()

Pingback: buy CBD()

Pingback: best cbd()

Pingback: royal cbd()

Pingback: royalcbd()

Pingback: juul pods mint()

Pingback: CBD gummies()

Pingback: CBD gummies()

Pingback: free app download()

Pingback: app for laptop()

Pingback: app for pc download()

Pingback: free download for windows 7()

Pingback: app download for windows()

Pingback: free download for windows pc()

Pingback: free download for windows 10()

Pingback: apps for pc()

Pingback: app for laptop()

Pingback: free download for windows 7()

Pingback: free download for windows 7()

Pingback: free download for windows pc()

Pingback: free windows app download()

Pingback: pc app free download()

Pingback: free download for windows 7()

Pingback: pc app()

Pingback: free download for windows()

Pingback: free games for laptop()

Pingback: free download for pc windows()

Pingback: free download for laptop()

Pingback: headout offers()

Pingback: nill()

Pingback: mobile applications()

Pingback: Mobile app development companies in Dubai()

Pingback: oral toys for couples()

Pingback: male stroker toy()

Pingback: Check Here()

Pingback: Schilderen Op Nummer vergelijken()

Pingback: adam and eve crystal clear 8 inch dildo()

Pingback: huge dildo()

Pingback: Vape Shop Near Me()

Pingback: Marijuana Dispensary()

Pingback: buy CBD oil()

Pingback: CBD oil 500mg()

Pingback: Kingpen()

Pingback: Marijuana Wax()

Pingback: men sex toys()

Pingback: kingcock suction cup dildo()

Pingback: vibrating anal plug with penis ring()

Pingback: bayan parfüm()

Pingback: cannabis culture()

Pingback: pocket pussy()

Pingback: CBD()

Pingback: Improve Customer Profitability()

Pingback: sex at home()

Pingback: most realistic stroker()

Pingback: giant dildo()

Pingback: hairdressing scissors()

Pingback: beste rijschool rotterdam()

Pingback: Dank Vapes()

Pingback: Glock 17()

Pingback: professional hairdressing scissors()

Pingback: barbering scissors()

Pingback: Mark Konrad Chinese Scissors()

Pingback: left handed scissors()

Pingback: publicité()

Pingback: hairdressing scissors icandy()

Pingback: yasaka scissors()

Pingback: Contact()

Pingback: hairdressing scissors()

Pingback: cbd oil Australia()

Pingback: best way to()

Pingback: dildo()

Pingback: VAPE CARTRIDGES()

Pingback: easy money online()

Pingback: Local pest control companies near me()

Pingback: curved vibrator()

Pingback: easun power()

Pingback: mens rings online()

Pingback: free download for windows 8()

Pingback: g gasm rabbit toy()

Pingback: apps download for windows 7()

Pingback: free download for windows 7()

Pingback: app for pc download()

Pingback: free app for pclaptop()

Pingback: app free download for windows 7()

Pingback: free laptop games download()

Pingback: free download for windows()

Pingback: app free download for windows 7()

Pingback: free laptop games download()

Pingback: app for laptop()

Pingback: free download for windows 7()

Pingback: app download for windows()

Pingback: free games for laptop()

Pingback: games free download for windows 8()

Pingback: app free download for windows 7()

Pingback: viagra health store()

Pingback: pc app()

Pingback: free download for windows 7()

Pingback: free apps for pc download()

Pingback: free download for windows pc()

Pingback: moon rocks()

Pingback: virtual mastercard card buy()

Pingback: Rick simpson oil()

Pingback: buy cannabis oil()

Pingback: study in ukraine()

Pingback: ban hoc thong minh()

Pingback: hairdressing scissors matsui()

Pingback: Retirement Planning Omaha()

Pingback: best CBD oil()

Pingback: junk car removal calgary()

Pingback: cash for cars calgary()

Pingback: 15% minoxidil with finasteride()

Pingback: discount cialis()

Pingback: elite chinese scissors()

Pingback: best CBD gummies()

Pingback: best CBD oil()

Pingback: Chiang Mai()

Pingback: best CBD gummies()

Pingback: web scraping()

Pingback: best Royal CBD oil()

Pingback: CBD oil()

Pingback: best Royal CBD oil()

Pingback: Royal CBD oil()

Pingback: best CBD gummies()

Pingback: CBD gummies for pain()

Pingback: Royal CBD()

Pingback: CBD pills()

Pingback: buy CBD()

Pingback: Royal CBD()

Pingback: carte prepagate()

Pingback: CBD oil()

Pingback: inflatable paddle board()

Pingback: James may net worth()

Pingback: app apk for pc download()

Pingback: pc games free download for windows 10()

Pingback: dispensary near me()

Pingback: how to maintain your sanity()

Pingback: g spot vibrator()

Pingback: adam and eve vibrators()

Pingback: stroker toy()

Pingback: best pocket pussy()

Pingback: butterfly stimulator()

Pingback: CBD capsules()

Pingback: best CBD pills()

Pingback: porn()

Pingback: CBD oil()

Pingback: cialis canada()

Pingback: purchase Northern Lights Marijuana Strain()

Pingback: pegging set()

Pingback: chubby dildo()

Pingback: porno()

Pingback: Porno()

Pingback: extension sleeve()

Pingback: butt plug review()

Pingback: dank vapes()

Pingback: Masala Machine()

Pingback: CBD products()

Pingback: Royal CBD()

Pingback: best CBD oil()

Pingback: Movie Download Site()

Pingback: best cbd cream for pain()

Pingback: best cbd cream for pain()

Pingback: cialis 20 mg()

Pingback: Buy Cockatoo()

Pingback: LSD Blotters()

Pingback: Optics()

Pingback: Buy Weed Online()

Pingback: DMT for Sale()

Pingback: Movie Download Site()

Pingback: Buy Weed Online()

Pingback: 50mg viagra()

Pingback: Movie Download Site()

Pingback: Canadain viagra()

Pingback: Juul Pods()

Pingback: when will generic cialis be available()

Pingback: Mango Juul Pods()

Pingback: http://clefgroup1.jigsy.com/entries/general/Successful-Home-Business-Tips-That-Set-You-Apart()

Pingback: Juul mint pods()

Pingback: https://www.intensedebate.com/people/gmodfree15()

Pingback: buy crystal meth online()

Pingback: cialis 5 mg()

Pingback: buy weed online()

Pingback: silicone strapless strap on()

Pingback: 8 inches dildo()

Pingback: best dildo()

Pingback: adam and eve sex toys()

Pingback: THC VAPE OIL()

Pingback: Dank Vapes()

Pingback: Legal Smoke Shop Near Me Open()

Pingback: Consultant SEO()

Pingback: buy adderall online()

Pingback: cialis otc()

Pingback: buy ambien online legally()

Pingback: vape shops near me()

Pingback: buy valium online()

Pingback: buy oxycodone online()

Pingback: Buy exotic carts()

Pingback: تيشرت()

Pingback: English bulldog puppies for sale()

Pingback: buy CBD oil()

Pingback: MALWAREBYTES BROWSER GUARD REVIEW()

Pingback: xanax online cheap()

Pingback: best CBD oil for dogs()

Pingback: dankwoods top shelf()

Pingback: best CBD oil for arthritis()

Pingback: best CBD oil for pain()

Pingback: best CBD oil for dogs()

Pingback: best CBD oil for sleep()

Pingback: goodrx cialis()

Pingback: best CBD oil for sleep()

Pingback: best CBD cream for arthritis pain()

Pingback: buy CBD oil()

Pingback: best CBD oil for arthritis()

Pingback: best CBD oil for pain()

Pingback: best CBD oil()

Pingback: levitra vs viagra()

Pingback: CBD oil near me()

Pingback: best CBD oil()

Pingback: best CBD oil()

Pingback: best CBD oil()

Pingback: best CBD gummies()

Pingback: best CBD oil()

Pingback: best CBD gummies()

Pingback: best CBD oil()

Pingback: best CBD gummies()

Pingback: best CBD oil()

Pingback: best CBD gummies()

Pingback: best CBD gummies()

Pingback: best CBD gummies()

Pingback: Buy Xanax online()

Pingback: cialis black()

Pingback: Xanax bars for sale()

Pingback: free download for windows pc()

Pingback: apk free download for windows 7()

Pingback: apps download for pc()

Pingback: apk free download for windows 10()

Pingback: free games download for windows 8()

Pingback: free games download for windows 8()

Pingback: free app download()

Pingback: free download for windows 10()

Pingback: apps download for windows 7()

Pingback: free download for pc()

Pingback: free download for windows 8()

Pingback: app free download for windows 7()

Pingback: free download for windows pc()

Pingback: Buy Nembutal bitcoins()

Pingback: free download for pc()

Pingback: free download for windows 7()

Pingback: free download for pc windows()

Pingback: viagra generic()

Pingback: apps for pc()

Pingback: Husky Puppies for Sale()

Pingback: app for laptop()

Pingback: apps download for windows 8()

Pingback: app for pc()

Pingback: free download for windows 8()

Pingback: apps download for pc()

Pingback: free apps for pc download()

Pingback: online pharmacy hydrocodone()

Pingback: Buy Fake Money That Looks Real()

Pingback: Buy Undetectable Fake Money Online()

Pingback: viagra 50mg()

Pingback: Fake Money That Looks Real()

Pingback: generic viagra 100mg()

Pingback: Order Hydrocodone Online Overnight()

Pingback: Packwoods Where To Buy()

Pingback: slot machine bonus()

Pingback: Fake Dankwoods()

Pingback: Order Valium Online Overnight()

Pingback: Free Robux Generator()

Pingback: Brand Awareness()

Pingback: viagra 50mg()

Pingback: Stiiizy()

Pingback: Creation des sites web()

Pingback: Freelance Jobs()

Pingback: affiliate marketing lead system()

Pingback: marketing online cursus()

Pingback: Free Premium Wordpress Themes()

Pingback: vape shop near me()

Pingback: win at online roulette()

Pingback: knight rider kitt for sale()

Pingback: win at online roulette()

Pingback: Websites To Get Free Robux()

Pingback: Earn Free Robux Here()

Pingback: win at online casino()

Pingback: how to win at casino()

Pingback: make money fast()

Pingback: drone()

Pingback: vape shop near me()

Pingback: best non prescription ed pills()

Pingback: Dank Vapes Cartridges()

Pingback: DR. MANPREET BAJWA CBD Fraud()

Pingback: contextual()

Pingback: erectile dysfunction drug()

Pingback: 710 King Pen Cartridges()

Pingback: kratom near me()

Pingback: bàn học cho bé gái()

Pingback: best CBD oil UK()

Pingback: CBD oils()

Pingback: CBD oil for depression()

Pingback: CBD oil()

Pingback: Buy Weed Online()

Pingback: детские стихи сша купить()

Pingback: best CBD oils()

Pingback: Ne Yo Say It Lyrics()

Pingback: He’s Soo Cute Lyrics Madhu Priya()

Pingback: русский язык 1 класс()

Pingback: Blessed CBD()

Pingback: Marijuanas Dispensary Near Me()

Pingback: Cannabis Online()

Pingback: CBD oil for pain()

Pingback: CBD products()

Pingback: CBD oils UK()

Pingback: best CBD oil()

Pingback: Blessed CBD()

Pingback: CBD oil UK()

Pingback: best CBD oils()

Pingback: free instagram followers()

Pingback: erectile dysfunction pills()

Pingback: seo services hong kong()

Pingback: fraud()

Pingback: Vape shop Near Me()

Pingback: Buy Weed Online()

Pingback: Buy Weed Online()

Pingback: search engine optimisation services()

Pingback: Youtube To Downloader Mp4()

Pingback: WinRAR Serial Key()

Pingback: AdGuard Premium Lifetime Subscription()

Pingback: Freemake Video Converter Crack()

Pingback: best affiliate marketing platforms 2020()

Pingback: what is affiliate marketing in hindi()

Pingback: affiliate marketing what is cpa()

Pingback: NordVPN Premium Account()

Pingback: what is affiliate marketing experience()

Pingback: Movavi Video Converter Crack()

Pingback: IDM With Crack()

Pingback: beginners affiliate marketing()

Pingback: canadian online pharmacy()

Pingback: Research chemicals for sale()

Pingback: شركة تنظيف ابوظبي()

Pingback: Best Cleaning Company in Abu Dhabi()

Pingback: Percocet for sale Craigslist()

Pingback: send large file()

Pingback: AKC German Shepherd dogs for sale()

Pingback: Buy Xanax online()

Pingback: online brands()

Pingback: ΚΑΖΙΝΑ ΝΙΚΑΙΑ()

Pingback: wartaekonomi()

Pingback: Earn Money Online()

Pingback: Work from Home Jobs()

Pingback: Online jobs()

Pingback: Work from home()

Pingback: Earn Money Online()

Pingback: Make Money from Home()

Pingback: Make Money from Home()

Pingback: best online pharmacy()

Pingback: Online Jobs()

Pingback: Earn Money Online()

Pingback: Work from Home Jobs()

Pingback: Make Money from Home()

Pingback: Work from home()

Pingback: cialis generic()

Pingback: Online Jobs()

Pingback: Silicone Baking Mats()

Pingback: Silicone Baking Mats()

Pingback: how to get free robux()

Pingback: bitcoin casino()

Pingback: OnHax Me()

Pingback: OnHaxx()

Pingback: OnHaxx()

Pingback: Gelato()

Pingback: app free download for windows 7()

Pingback: app download for pc()

Pingback: pc games for windows 7()

Pingback: free download for windows 7()

Pingback: free download for laptop pc()

Pingback: apps download for windows 10()

Pingback: app for pc free download()

Pingback: Cookies Cartridges()

Pingback: free download for windows pc()

Pingback: free download for windows 7()

Pingback: vape carts()

Pingback: free download for pc()

Pingback: free apps download for windows 7()

Pingback: generic cialis()

Pingback: pc games for windows 8()

Pingback: Purchase Weed Online()

Pingback: kratom()

Pingback: Marijuana Strains()

Pingback: Kratom Near Me()

Pingback: online levitra()

Pingback: flow bar disposable vape()

Pingback: Movie Download Site()

Pingback: easy online()

Pingback: OnHaxx()

Pingback: vardenafil pill()

Pingback: лучшее адальт-видео онлайн()

Pingback: Umzugsfirma Wien()

Pingback: easy to download seriale turcesti()

Pingback: Weed Shop()

Pingback: Buy Weed Online()

Pingback: Dank Vapes()

Pingback: vardenafil 10 mg()

Pingback: Jed Fernandez()

Pingback: AC maintenance dubai()

Pingback: Streetwear()

Pingback: e-library()

Pingback: doubleu casino online casino()

Pingback: e-library()

Pingback: bombar instagram()

Pingback: Sonia Randhawa()

Pingback: app for pc()

Pingback: Local University()

Pingback: job posting()

Pingback: online slots real money()

Pingback: birman kittens for sale()

Pingback: ragdoll kittens for sale near me()

Pingback: Buy fake money()

Pingback: Buy counterfeit money online()

Pingback: servisi/ aıdınlıkevler profilo servisi()

Pingback: sincan arçelik servisi()

Pingback: dikmen siemens servisi()

Pingback: Sonia Randhawa()

Pingback: Ayurveda Online Shop()

Pingback: viagra cheap()

Pingback: Sonia Randhawa()

Pingback: exotic cartridges()

Pingback: kratom near me()

Pingback: kratom near me()

Pingback: brass knuckles for sale()

Pingback: Escorts()

Pingback: online casinos for usa players()

Pingback: Buy Weed Online()

Pingback: cbd oil for cats()

Pingback: Sonia Randhawa()

Pingback: maeng da kratom()

Pingback: Sonia Randhawa()

Pingback: Sonia Randhawa()

Pingback: fake money for sale()

Pingback: seo hong kong internet marketing()

Pingback: international seo hong kong()

Pingback: seo agency hong kong()

Pingback: 5euros()

Pingback: Kingpen()

Pingback: Dank Vapes()

Pingback: casino games()

Pingback: pest control near me()

Pingback: cbd for cats()

Pingback: cbd oil for pain()

Pingback: pest control()

Pingback: Sonia Randhawa()

Pingback: commercial pest control near me()

Pingback: Sonia Randhawa()

Pingback: Sonia Randhawa()

Pingback: Keto Diet Pills()

Pingback: cialis online reviews()

Pingback: bookstore()

Pingback: beagle puppies()

Pingback: Buy spice online()

Pingback: loans online()

Pingback: great dane puppies()

Pingback: maltipoo puppies for sale()

Pingback: SEO Melbourne()

Pingback: Jazzct.com()

Pingback: consultant seo()

Pingback: 5euros()

Pingback: reparatii indoituri()

Pingback: pdr cluj()

Pingback: loans for bad credit()

Pingback: Men's supplements Review()

Pingback: best steroids for weight loss()

Pingback: Phen375()

Pingback: Workshop()

Pingback: Diet Pills()

Pingback: instant loans()

Pingback: سکس خانوم نوروزی از کون()

Pingback: Buy Best Testosterone Booster()

Pingback: Fitness Blog()

Pingback: Exterminators()

Pingback: Commercial pest control service()

Pingback: viagra 100mg()

Pingback: Exterminators()

Pingback: Pest control()

Pingback: trick for recharge()

Pingback: Flipkart Daily Trivia Answers()

Pingback: Flipkart Kya Bolti Public Answers()

Pingback: Top 10 Best Sellers Education()

Pingback: V Tight Gel in Stores()

Pingback: online casino poker real money()

Pingback: Thesis()

Pingback: best real money online casinos()

Pingback: Dr. Oz's 'Miracle Fat Burner'()

Pingback: best real money online casinos()

Pingback: casino bonus 300()

Pingback: cialis to buy()

Pingback: سكس بنات صغيرة()

Pingback: Safety()

Pingback: kratom wholesale()

Pingback: Kratom powder()

Pingback: Boxer puppies()

Pingback: maeng da Kratom()

Pingback: Pitbull Puppies for sale()

Pingback: Australian Shepherd Puppies for sale()

Pingback: Doberman pinscher Puppies for sale()

Pingback: Reverse Phone Number Lookup()

Pingback: buy cialis()

Pingback: vegas casino online real money()

Pingback: casino real money()

Pingback: cialis 5 mg()

Pingback: big black cock enter's rajapandi's tender asshole()

Pingback: real viagra pharmacy prescription()

Pingback: cialis 20()

Pingback: 20 cialis()

Pingback: Handlateknik()

Pingback: generic for cialis()

Pingback: غرور()

Pingback: ثقة()

Pingback: الخيانة()

Pingback: حلوه()

Pingback: الم()

Pingback: Escort amsterdam()

Pingback: Plus Sizes()

Pingback: Kratom near me()

Pingback: 5euros()

Pingback: viagra online()

Pingback: RoyalCBD()

Pingback: Royal CBD()

Pingback: RoyalCBD.com()

Pingback: https://royalcbd.com/terpenes/()

Pingback: Royal CBD()

Pingback: RoyalCBD()

Pingback: RoyalCBD()

Pingback: https://royalcbd.com/does-cbd-get-you-high/()

Pingback: Royal CBD()

Pingback: RoyalCBD.com()

Pingback: cbg cbda cbn cbc cbdv()

Pingback: RoyalCBD()

Pingback: RoyalCBD.com()

Pingback: https://royalcbd.com/cbd-dosage-for-dogs()

Pingback: Sell rolex()

Pingback: RoyalCBD.com()

Pingback: Buy Legal Buds Online()

Pingback: Sell jewelry()

Pingback: is cbd legal in wisconsin()

Pingback: cbd washington dc()

Pingback: virginia cbd()

Pingback: RoyalCBD.com()

Pingback: oklahoma cbd()

Pingback: cbd oil utah()

Pingback: diamond engagement rings()

Pingback: RoyalCBD()

Pingback: RoyalCBD()

Pingback: RoyalCBD()

Pingback: is cbd legal in ohio()

Pingback: Royal CBD()

Pingback: Corgi puppies()

Pingback: RoyalCBD()

Pingback: https://royalcbd.com/pennsylvania/()

Pingback: cbd new mexico()

Pingback: cbd new york()

Pingback: Royal CBD()

Pingback: new jersey()

Pingback: RoyalCBD.com()

Pingback: 먹튀검증()

Pingback: RoyalCBD.com()

Pingback: cbd mississippi()

Pingback: https://royalcbd.com/missouri/()

Pingback: slots real money()

Pingback: is cbd legal in minnesota()

Pingback: michigan cbd()

Pingback: RoyalCBD.com()

Pingback: maryland()

Pingback: cbd maine()

Pingback: is cbd legal in kentucky()

Pingback: is cbd legal in illinois()

Pingback: cbd iowa()

Pingback: RoyalCBD()

Pingback: https://royalcbd.com/georgia/()

Pingback: Kitten Carriers()

Pingback: delaware()

Pingback: Royal CBD()

Pingback: arkansas()

Pingback: is cbd legal in colorado()

Pingback: california cbd()

Pingback: cbd oil arizona()

Pingback: RoyalCBD()

Pingback: Royal CBD()

Pingback: https://royalcbd.com/cbd-oil-vs-hemp-seed-oil/()

Pingback: Royal CBD()

Pingback: https://royalcbd.com/how-to-make-cbd-gummies-at-home/()

Pingback: cbd oil timeline()

Pingback: RoyalCBD()

Pingback: RoyalCBD.com()

Pingback: how long does cbd oil last()

Pingback: Royal CBD()

Pingback: https://royalcbd.com/vaping-cbd-oil-e-liquid/()

Pingback: cbd isolate vs full spectrum broad spectrum()

Pingback: why cannabis affects people differently()

Pingback: RoyalCBD()

Pingback: Royal CBD()

Pingback: https://royalcbd.com/cbd-legal-status/()

Pingback: gifts store()

Pingback: matryoshka()

Pingback: states marijuana laws map()

Pingback: книги для детей()

Pingback: RoyalCBD()

Pingback: russian characters()

Pingback: CBD pills()

Pingback: russian last names()

Pingback: THC Cartridge()

Pingback: online casinos real money()

Pingback: اغاني()

Pingback: MILF()

Pingback: lesbian porn()

Pingback: sie sucht ihn baden württemberg()

Pingback: online casinos usa()

Pingback: rust combat tag server()

Pingback: Pass PMP()

Pingback: MALWAREBYTES ANTI ROOTKIT()

Pingback: viagra generic name()

Pingback: investment sales broker()

Pingback: Electrician SEO()

Pingback: viagra online prescription free()

Pingback: free download for pc()

Pingback: free download for pc windows()

Pingback: pc games for windows 7()

Pingback: pc games download()

Pingback: Fakaza mp3 download()

Pingback: buy cialis online()

Pingback: Escort amsterdam()

Pingback: viagra 100mg()

Pingback: Business Coach()

Pingback: buy viagra online usa()

Pingback: anvelope chisinau()

Pingback: Online Impacts()

Pingback: options trading()

Pingback: Apple support()

Pingback: tadalafil 10 mg()

Pingback: generic viagra without subscription walmart()

Pingback: embedded system()

Pingback: pets news websites()

Pingback: semrush competitive density()

Pingback: Cavachon Puppies()

Pingback: DANKWOODS()

Pingback: exotic carts review()

Pingback: Teacup Puppies For Sale()

Pingback: Pc hilfe meilen()

Pingback: Escort amsterdam()

Pingback: generic for viagra()

Pingback: Dank Cartridges()

Pingback: Kingpen()

Pingback: Thc Vape Oil()

Pingback: ed meds online without doctor prescription()

Pingback: Employee Benefits Chicago()

Pingback: Brass Knuckles Vape()

Pingback: Thc Vape Cartridge()

Pingback: gamer()

Pingback: Dank Vapes Cartridge()

Pingback: Windows RDP from Linux()

Pingback: viagra cost()

Pingback: Mario Carts()

Pingback: Motivational Speaker()

Pingback: generic cialis()

Pingback: best ahmedabad escorts agency()

Pingback: indian visa application()

Pingback: Visa de India()

Pingback: indian visa()

Pingback: indian visa()

Pingback: viagra buy()

Pingback: indian visa online()

Pingback: indian visa online()

Pingback: india visa online()

Pingback: Golden Retriever()

Pingback: Shih Tzu Puppies For Sale()

Pingback: Miniature Yorkshire Terrier Puppies For Sale Near Me()

Pingback: Shiba Inu()

Pingback: Pug Puppies For Sale Near Me()

Pingback: Teacup Maltese For Sale()

Pingback: Poodle Puppies For Sale Near Me()

Pingback: Cavapoo()

Pingback: Russian Toy Puppies for sale()

Pingback: Pomeranian Puppies For Sale Near Me()

Pingback: German Shepherd Puppies For Sale Near Me()

Pingback: sleepers shoes()

Pingback: Link()

Pingback: viagra prescription()

Pingback: buy tadalafil online()

Pingback: TOURS()

Pingback: viagra pills()

Pingback: website()

Pingback: more info here()

Pingback: best place to buy cialis online reviews()

Pingback: داستان سکسی مامان()

Pingback: casino online slots()

Pingback: seo training course hong kong()

Pingback: https://sharadadvertising.com/()

Pingback: corporate seo training hong kong()

Pingback: search engine optimization training hong kong()

Pingback: Vishwas Thakkar()

Pingback: search engine optimization training hong kong()

Pingback: indian visa()

Pingback: indian visa()

Pingback: indian visa application()

Pingback: eta new zealand()

Pingback: new zealand tourist visa()

Pingback: eta new zealand()

Pingback: Pendik Escort()

Pingback: Kartal Escort()

Pingback: prostate massager()

Pingback: Pembroke Welsh Corgi Puppies()

Pingback: european doberman()

Pingback: online gambling()

Pingback: 100% undetectable counterfeit()

Pingback: fishscale cocaine()

Pingback: Xxl Pitbull Puppies For Sale Cheap()

Pingback: Savannah Cat For Sale()

Pingback: Blue Cat()

Pingback: Maine Coon Kittens For Sale()

Pingback: Bengal Cat For Sale Near Me()

Pingback: Munchkin Kittens For Sale In Michigan()

Pingback: شحن فيبوكس مجانا()

Pingback: شحن فيبوكس مجانا()

Pingback: شحن فيبوكس مجانا()

Pingback: v bucks شحن()

Pingback: droga5.net()

Pingback: Old English Bulldog()

Pingback: Boston Terrier Puppies For Sale()

Pingback: Bassett Hound()

Pingback: Samoyed Puppies()

Pingback: Alaskan Malamute Puppies()

Pingback: Yorkshire Terrier Puppies For Sale()

Pingback: Border Collie Puppies For Sale Near Me()

Pingback: American Bulldog Puppies()

Pingback: is it possible for me to buy viagra from canada()

Pingback: Cannabis Oil for Sale()

Pingback: Cannabis Oil()

Pingback: Weed Wax()

Pingback: اغاني()

Pingback: Marijuana Wax()

Pingback: Marijuana Vapes()

Pingback: Buy Weed Online()

Pingback: Marijuana Strains()

Pingback: where is the best place to buy viagra online()

Pingback: purchase cialis()

Pingback: Venice photography()

Pingback: CDR WRITING SERVICES()

Pingback: visit this site()

Pingback: where to buy viagra in miami location()

Pingback: apps for pc download()

Pingback: software download for windows 7()

Pingback: Group health insurance plans()

Pingback: health insurance broker()

Pingback: Employee health insurance plans()

Pingback: health insurance broker()

Pingback: Employee benefits()

Pingback: Long Haired Chihuahua Teacup Chihuahua()

Pingback: English Bulldog Puppies For Sale()

Pingback: Labrador Retriever Puppies For Sale()

Pingback: Bee Via Thailand()

Pingback: Pug Puppies For Sale In Pa()

Pingback: Blue French Bulldog()

Pingback: physiotherapie für hunde()

Pingback: Boston Terrier Puppies()

Pingback: how to get cheap viagra()

Pingback: cannabis4homes.com()

Pingback: soviet ushanka()

Pingback: Medical Marijuana()

Pingback: Medical Marijuana()

Pingback: Rick Simpson Oil()

Pingback: big dildo()

Pingback: internet radio()

Pingback: Hybrid Strains()

Pingback: gamdom()

Pingback: gel kit for nails()

Pingback: Indica Strains()

Pingback: Sativa Strains()

Pingback: THC oil()

Pingback: Acapulco Gold Strain()

Pingback: Banana Kush Strain()

Pingback: Шины в Кишиневе()

Pingback: bitsler()

Pingback: Blue Dream Strain()

Pingback: stake.com()

Pingback: wolfbet()

Pingback: Mt. Kenya()

Pingback: cialis brand()

Pingback: White Rhino Strain()

Pingback: Cinderella 99 Strain()

Pingback: Viagra 120mg uk()

Pingback: Death Star Strain()

Pingback: Financial career()

Pingback: Working Capital()

Pingback: Do Si Dos Strain()

Pingback: Mastercard Corporate Credit Card()

Pingback: Viagra 200 mg without a prescription()

Pingback: Golden Goat Strain()

Pingback: Pineapple Express Strain()

Pingback: Viagra 100mg price()

Pingback: Maui Waui Strain()

Pingback: Cannatonic Strain()

Pingback: Bubba Kush Strain()

Pingback: cost of Viagra 50mg()

Pingback: Alien Kush Strain()

Pingback: tradecoin()

Pingback: Gorilla Glue No 4 Strain()

Pingback: Cherry Pie Strain()

Pingback: Viagra 130 mg cheap()

Pingback: Viagra 130 mg united kingdom()

Pingback: Viagra 25 mg without a doctor prescription()

Pingback: online viagra()

Pingback: White Shark Strain()

Pingback: Strawberry Cough Strain()

Pingback: tadalafil()

Pingback: start your own internet marketing business()

Pingback: male masturbators()

Pingback: True Og Strain()

Pingback: Denver SEO expert()

Pingback: Blue Cheese Strain()

Pingback: Cialis 10 mg coupon()

Pingback: video production denver()

Pingback: denver hvac home services()

Pingback: Cialis 60mg prices()

Pingback: Blueberrry Strain()

Pingback: اغانى شعبى()

Pingback: Hawaiian Snow Strain()

Pingback: Valentine X Strain()

Pingback: christian video marketing()

Pingback: hire a bartender()

Pingback: G13 Strain()

Pingback: Black Jack Strain()

Pingback: cheap viagra()

Pingback: Chemdawg Strain()

Pingback: King Kung Kush Strain()

Pingback: Obama Og Kush Strain()

Pingback: Head Cheese Strain()

Pingback: computer recycling service newbury()

Pingback: how to purchase Cialis 40 mg()

Pingback: Wedding Cake Strain()

Pingback: viagra sale()

Pingback: order viagra()

Pingback: Gelato Strain()

Pingback: order cialis()

Pingback: Tangerine Dream Strain()

Pingback: Romulan Strain()

Pingback: Cialis 10mg without a prescription()

Pingback: Sour Tangie Strain()

Pingback: Euforia Strain()

Pingback: Headband Kush Strain()

Pingback: Cialis 10 mg no prescription()

Pingback: Henry Viii Strain()

Pingback: Honey Bud Strain()

Pingback: Cialis 40mg australia()

Pingback: Cherry Ak 47 Strain()

Pingback: Professional Seo Training Hong Kong()

Pingback: Corporate Seo Training In Hong Kong()

Pingback: Lead Generation In Digital Marketing Hong Kong()

Pingback: Hongkong Local Seo Training()

Pingback: Local Seo Training Hong Kong()

Pingback: Digital Strategy Training Hong Kong()

Pingback: Seo Training In Hk()

Pingback: Local Seo Training In Hk()

Pingback: Super Girl Scout Cookies Strain()

Pingback: where can i buy Cialis 40mg()

Pingback: apex legends hile satın al()

Pingback: Lsd Strain()

Pingback: Plastic Surgery in Turkey()

Pingback: Big Wreck Strain()

Pingback: Amnesia Strain()

Pingback: buy cheap sildenafil()

Pingback: pubg mobile emülatör hile()

Pingback: Wiz Khalifa Og Strain()

Pingback: how to purchase sildenafil 150mg()

Pingback: 메리트카지노()

Pingback: exchange crypto()

Pingback: Fruity Juice Strain()

Pingback: how to purchase levitra 60mg()

Pingback: Norwegian Forest Kittens For Sale Near Me()

Pingback: Australian Shepherd()

Pingback: Fruity Thai Strain()

Pingback: fluffy kittens for sale()

Pingback: THC VAPE OIL()

Pingback: Agent Orange Strain()

Pingback: cheapest lasix 100mg()

Pingback: Platinum Gsc Strain()

Pingback: Buddah Og Strain()

Pingback: sex toy review()

Pingback: AU Tradeline scammers()

Pingback: Flying Dragon Strain()

Pingback: furosemide 100 mg pharmacy()

Pingback: Blackberry Kush Strain()

Pingback: Super Og Master Kush Strain()

Pingback: cialis()

Pingback: Violator Kush Strain()

Pingback: propecia 1 mg uk()

Pingback: Mango Haze Strain()

Pingback: Fuma Con Dios Strain()

Pingback: Queso Strain()

Pingback: Elephant Bud Strain()

Pingback: buy lexapro 10mg()

Pingback: Tangerine Haze Strain()

Pingback: best bullet vibrator()

Pingback: viagra without doctor prescription()

Pingback: find a builder near me()

Pingback: Conspiracy Kush Strain()

Pingback: dinh cu canada()

Pingback: viagra()

Pingback: rodos feribot()

Pingback: abilify 15mg online()

Pingback: Haleys Comet Strain()

Pingback: how to buy actos 30 mg()

Pingback: Bible Study()

Pingback: money man ft lil baby - 24()

Pingback: Nyc Diesel Strain()

Pingback: Trainwreck Strain()

Pingback: istanbul fetis escort()

Pingback: Cat Piss Strain()

Pingback: aldactone 100mg united kingdom()

Pingback: Grape Ape Strain()

Pingback: en uygun uçak bileti()

Pingback: Champagne Kush Strain()

Pingback: Blackberry Hashplant Strain()

Pingback: Himalaya Gold Strain()

Pingback: Fire Og Kush Strain()

Pingback: Hashberry Strain()

Pingback: Hells Angel Og Strain()

Pingback: Yeti Og Strain()

Pingback: Remedy Strain()

Pingback: allegra 120mg uk()

Pingback: Ace Of Spades Strain()

Pingback: Sweet And Sour Strain()

Pingback: Cherry Kush Strain()

Pingback: Super Jack Herer Strain()

Pingback: King Louis Xiii Strain()

Pingback: allopurinol 300mg coupon()

Pingback: Moby Dick Strain()

Pingback: Halo Og Strain()

Pingback: Blueberry Haze Strain()

Pingback: Arjan Ultra Haze Strain()

Pingback: Mango Kush Strain()

Pingback: Blues Strain()

Pingback: amaryl 2 mg no prescription()

Pingback: viagra sans ordonnance en pharmacie()

Pingback: Alien Dawg Strain()

Pingback: Super Snowdawg Strain()

Pingback: macca()

Pingback: amoxicillin 500 mg uk()

Pingback: Super Grand Daddy Purple Strain()

Pingback: Pre 98 Bubba Kush Strain()

Pingback: پیش بینی بازی انفجار()

Pingback: hat mac ca lam dong()

Pingback: Critical Sensi Star Strain()

Pingback: ampicillin 500 mg online()

Pingback: Fog Strain()

Pingback: Heavy Hitter Strain()

Pingback: Holland Diesel Strain()

Pingback: Top 44 Strain()

Pingback: macadamia mystrikingly()

Pingback: antabuse 250 mg without a prescription()

Pingback: Blueberry Kush Strain()

Pingback: Euphoria Strain()

Pingback: Willys Wonder Strain()

Pingback: Darth Vader Og Strain()

Pingback: Paris Og Strain()

Pingback: antivert 25 mg medication()

Pingback: Huron Strain()

Pingback: viagra online()

Pingback: arava 20mg tablet()

Pingback: emma-shop()

Pingback: Erkle Spacedog Strain()

Pingback: Dj Short Blueberry Strain()

Pingback: strattera 18mg uk()

Pingback: Yeager Strain()

Pingback: Sweet Afghani Delicious Strain()

Pingback: Jupiter Kush Strain()

Pingback: Jedi Kush Strain()

Pingback: Og Strain()

Pingback: Yampa Valley Strain()

Pingback: buy viagra pills()

Pingback: best sex toys()

Pingback: aricept 10mg without prescription()

Pingback: Uw Strain()

Pingback: Diesel Strain()

Pingback: Incredible Hulk Strain()

Pingback: Ethiopian Highlands Strain()

Pingback: Island Maui Haze Strain()

Pingback: Sour Jack Strain()

Pingback: Voodoo Strain()

Pingback: Fruit Strain()

Pingback: Queen Mother Strain()

Pingback: Haze Strain()

Pingback: Allen Wrench Strain()

Pingback: Ocd Strain()

Pingback: arimidex 1 mg price()

Pingback: Gorilla Glue Thc Oil Strain()

Pingback: Holy Grail Kush Thc Strain()

Pingback: visit here ΠΑΝΟΣ ΓΕΡΜΑΝΟΣ()

Pingback: Og Kush Thc Oil()

Pingback: blogcaodep.com()

Pingback: Sour Diesel Thc Oil()

Pingback: Amnesia Thc Oil()

Pingback: Ak47 Thc Oil()

Pingback: Blackberry Kush Thc Oil()

Pingback: tamoxifen 10mg prices()

Pingback: use this link panos germanos()

Pingback: buy ashwagandha 60caps()

Pingback: generic cialis india()

Pingback: tabakvervanger()

Pingback: cell phone()

Pingback: atarax 25mg prices()

Pingback: witgoed reparatie()

Pingback: augmentin 500/125 mg cost()

Pingback: all vape stores online()

Pingback: the muppets mah na mah na()

Pingback: cheapest avapro 300mg()

Pingback: buy weed online()

Pingback: tabaksvervanger()

Pingback: discover card viagra()

Pingback: avodart 0,5 mg pharmacy()

Pingback: baclofen 10mg coupon()

Pingback: pakistan solar system price()

Pingback: https://www.telocard.com/()

Pingback: where can i buy bactrim 800/160 mg()

Pingback: Gerüstbau()

Pingback: Aussie Breeder()

Pingback: online viagra without subscription()

Pingback: benicar 10mg united states()

Pingback: yout'()

Pingback: cialis price india()

Pingback: havuz malzemeleri()

Pingback: Bodrum havuz kimyasallarý()

Pingback: sandalye()

Pingback: sývý klor()

Pingback: why not find out more ΑΠΟΦΡΑΞΕΙΣ()

Pingback: capath.vn()

Pingback: sweetiehouse.vn()

Pingback: kamado grill buying guide()

Pingback: Premarin 0,625mg coupon()

Pingback: purebred pitbull puppies for sale near me()

Pingback: Beretta 686()

Pingback: generic viagra without a doctor prescription()

Pingback: airsoft sniper rifles for sale()

Pingback: Assault rifles for sale()

Pingback: fluorococaine()

Pingback: magic mushroom starter kit()

Pingback: buy cialis usa()

Pingback: Beretta A400 Xtreme Plus Max 5()

Pingback: GLOCK GUNS FOR SALE()

Pingback: Buy Gun Online()

Pingback: Magic Mush Rooms()

Pingback: calcium carbonate 500mg nz()

Pingback: viagra without prescription()

Pingback: cardizem united states()

Pingback: viagra newsletter()

Pingback: casodex 50 mg pills()

Pingback: canada pharmacy viagra generic()

Pingback: catapres 100mcg pharmacy()

Pingback: ceclor 250 mg united states()

Pingback: hard sex porn()

Pingback: CBD Oil Extract()

Pingback: ceftin no prescription()

Pingback: virtual credit card buy()

Pingback: celebrex 200 mg online()

Pingback: hat macca sai gon uy tin()

Pingback: hat-macca-77.webself.net()

Pingback: Dank Vapes()

Pingback: celexa tablet()

Pingback: virtual card buy for make payment virtual credit card buy()

Pingback: şişme mont()

Pingback: yetkilendirilmiş yükümlü belgesi()

Pingback: cephalexin usa()

Pingback: burun düzeltme()

Pingback: su arıtma cihazı tavsiyesi()

Pingback: how to buy cipro 500 mg()

Pingback: claritin cheap()

Pingback: rivers casino()

Pingback: halkbank kart şifresi alma()

Pingback: vibrating cock rings()

Pingback: hrdf training course penang()

Pingback: haberler()

Pingback: ziraat bankası vadeli hesap faiz oranları()

Pingback: vegas casino online()

Pingback: casino game()

Pingback: canadian pharmacy viagra()

Pingback: casino online games()

Pingback: Muha Meds Watermelon 1000mg()

Pingback: gambling games()

Pingback: u2store.blogspot.com()

Pingback: fentanyl Patches()

Pingback: Reformhaus Wien()

Pingback: real casino online()

Pingback: buy instagram followers()

Pingback: learn more()

Pingback: parx casino online()

Pingback: best real casino online()

Pingback: slot machine games()

Pingback: accc car insurance()

Pingback: car insurances()

Pingback: cheap ed pills()

Pingback: hrdf training provider penang()

Pingback: car insurance quotes prices()

Pingback: Tenuate retard()

Pingback: approved pharmacy()

Pingback: generic viagra available in usa()

Pingback: o-dsmt()

Pingback: thc vape juice()

Pingback: aarp car insurance()

Pingback: Pure Colombian Cocaine()

Pingback: Fish scale cocaine()

Pingback: Change DMT()

Pingback: car insurances()

Pingback: Murang'a University()

Pingback: Maltipoo puppies for sale()

Pingback: vehicle insurance()

Pingback: strong herbal incense for sale()

Pingback: Buy Adderall 30mg online()

Pingback: Herbal Incense()

Pingback: car insurance quotes estimate()

Pingback: Dank Vapes()

Pingback: car insurance online()

Pingback: online car insurance quotes()

Pingback: personal loans()

Pingback: car insurance quotes comparison()

Pingback: brazzers()

Pingback: canadapharmacy.com()

Pingback: film()

Pingback: personal loans florida()

Pingback: Canadian generic viagra online()

Pingback: viagra use()

Pingback: payday loans with no credit check()

Pingback: payday loans for bad credit()

Pingback: installment loans texas()

Pingback: Custom Vest printing.()

Pingback: film()

Pingback: quick loans texas()

Pingback: bad credit loans lenders()

Pingback: Where to buy custom jewellery()

Pingback: canada pharmacy services()

Pingback: instant payday loans online()

Pingback: personal loan help()

Pingback: generic viagra online canadian pharmacy()

Pingback: can cbd oil help with pain?()

Pingback: Authority backlinks()

Pingback: pc apps download()

Pingback: cbd oil from colorado for cancer patients()

Pingback: btc canada()

Pingback: generic viagra in usa()

Pingback: pubg hileleri()

Pingback: cbd oil in ohio()

Pingback: visum indien()

Pingback: shelf life viagra()

Pingback: تأشيرة هندية()

Pingback: buy sildenafil()

Pingback: Indisch visum()

Pingback: buy cbd oil walmart()

Pingback: cbd hemp oil capsules 450 mg()

Pingback: where can i get sildenafil 100mg()

Pingback: ways to get and keep an erection()

Pingback: cbd oil milford ohio()

Pingback: Best Games for Nintendo()

Pingback: cbd oil for sale near me()

Pingback: where to buy viagra pills()

Pingback: cbd oil and anxiety()

Pingback: purchase generic viagra()

Pingback: CARGO VESSEL()

Pingback: cheap essay writing service us()

Pingback: Fancy Text Generator()

Pingback: payday loans no credit check()

Pingback: buy liquid viagra()

Pingback: academic essay writer()

Pingback: crypto canada()

Pingback: essay writing service uk()

Pingback: buy argumentative essay()

Pingback: best custom essay writing service()

Pingback: pharmacy canada (800) 901-0041()

Pingback: my homework help()

Pingback: cheapest essay writing service uk()

Pingback: order viagra online without a prescription()

Pingback: ed treatment()

Pingback: Buy Percocet online()

Pingback: premium assignments()

Pingback: fennec fox for sale()

Pingback: sugar glider for sale()

Pingback: paper writers for hire()

Pingback: eclectus()

Pingback: buy cleocin()

Pingback: indian ringneck()

Pingback: where can i buy viagra tablets()

Pingback: toucan bird()

Pingback: Generic viagra us()

Pingback: clomid 25mg generic()

Pingback: deniz ışın()

Pingback: clonidine for sale()

Pingback: Buy Testogen()

Pingback: clozaril 50mg pills()

Pingback: Buy viagra com()

Pingback: colchicine 0,5 mg online()

Pingback: Buy Ketamine online()

Pingback: cost of symbicort inhaler 160/4,5 mcg()

Pingback: generic cialis online canada()

Pingback: http://sadfaasdfasfafadsfa.com()

Pingback: where to buy combivent()

Pingback: coreg 12,5 mg coupon()

Pingback: essay writing services recommendations()

Pingback: compazine 5 mg for sale()

Pingback: Buy Ritalin 10mg online()

Pingback: ENTERPRISECARSALES.COM()

Pingback: coumadin 1 mg generic()

Pingback: my canadian website()

Pingback: Generic viagra us()

Pingback: cozaar cheap()

Pingback: price of viagra in delhi()

Pingback: help me write a thesis()

Pingback: customessaywriterbyz.com()

Pingback: Philadelphia Elibrary()

Pingback: crestor 10 mg nz()

Pingback: Canada meds viagra()

Pingback: how to buy cymbalta()

Pingback: Buy shatter online()

Pingback: dapsone 1000caps pharmacy()

Pingback: write my paper apa style()

Pingback: help writing thesis()

Pingback: viagra()

Pingback: ddavp pills()

Pingback: Arþiv araþtýrmasý()

Pingback: ATARAX 25MG PILLS()

Pingback: depakote prices()

Pingback: cost of diamox 250mg()

Pingback: where can i buy differin 15g()

Pingback: real feel dildos()

Pingback: aðýr ceza avukatý()

Pingback: diltiazem 30 mg without a prescription()

Pingback: 우리카지노()

Pingback: 샌즈카지노()

Pingback: 퍼스트카지노()

Pingback: 메리트카지노()

Pingback: doxycycline 100 mg tablet()

Pingback: xero accounting singapore()

Pingback: 코인카지노()

Pingback: how to buy dramamine()

Pingback: elavil pharmacy()

Pingback: online pharmacy canada()

Pingback: erythromycin 250 mg tablets()

Pingback: три поросенка аудиосказка()

Pingback: etodolac united states()

Pingback: русские сказки аудиокнига()

Pingback: Fyodor Dostoyevsky()

Pingback: where to buy flomax()

Pingback: cheap Amoxil()

Pingback: денискины рассказы слушать онлайн()

Pingback: аудиосказка гадкий утенок()

Pingback: flonase nasal spray no prescription()

Pingback: سکس داستانی()

Pingback: MORPHINE FOR SALE()

Pingback: garcinia cambogia caps tablet()

Pingback: Buy amnesia haze online()

Pingback: شحن فري فاير()

Pingback: موقع شحن جواهر فري فاير()

Pingback: شحن جواهر فري فاير()

Pingback: شحن فري فاير()

Pingback: geodon 40mg cheap()

Pingback: جواهر فري فاير()

Pingback: شحن جواهر فري فاير مجانا()

Pingback: شحن فري فاير()

Pingback: موقع شحن جواهر فري فاير()

Pingback: Jungle boys Sundae Driver()

Pingback: canadian drug()

Pingback: شحن فري فاير()

Pingback: موقع شحن جواهر فري فاير()

Pingback: buy hyzaar 12,5mg()

Pingback: شحن جواهر فري فاير()

Pingback: شحن جواهر فري فاير مجانا()

Pingback: Seattle exterminators()

Pingback: جواهر فري فاير()

Pingback: موقع شحن جواهر فري فاير()

Pingback: imdur 20mg canada()

Pingback: Seattle ants exterminators()

Pingback: cialis reviews()

Pingback: generic for cialis()

Pingback: find a life coach()

Pingback: cialis()

Pingback: imitrex otc()

Pingback: Exterminators in my area()

Pingback: Seattle exterminators()

Pingback: Methadone 10 Mg()

Pingback: Exterminators in my area()

Pingback: Seattle ants exterminators()

Pingback: Exterminators()

Pingback: cialis online()

Pingback: imodium no prescription()

Pingback: find more info()

Pingback: price of viagra()

Pingback: does viagra lower blood pressure()

Pingback: viagra generic()

Pingback: 3D Date()

Pingback: imuran 50 mg without prescription()

Pingback: 3D Concerts()

Pingback: canadian pharmacy viagra()

Pingback: mouse trap()

Pingback: how to purchase indocin()

Pingback: sign ups guaranteed()

Pingback: how to buy lamisil()

Pingback: zithromax 250 mg tablet price()

Pingback: buy Ambien online()

Pingback: Virtual Conventions()

Pingback: cost of levaquin 250 mg()

Pingback: Magic Mushroom grow kits()

Pingback: детские аудио книги бесплатно()

Pingback: avant consulting()

Pingback: generic viagra 100mg()

Pingback: Virtual Reality Learning()

Pingback: lopressor 50mg no prescription()

Pingback: Buy Phentermine online()

Pingback: oxycodone for sale()

Pingback: Buy Roxicodone online()

Pingback: Buy valium online()

Pingback: buy luvox 50 mg()

Pingback: buy Xanax online()

Pingback: Tramadol for sale()

Pingback: Buy Hydrocodone Online()

Pingback: Percocet for sale online()

Pingback: Mushroom growing kit()

Pingback: magic mushroom spores for sale()

Pingback: Magic Mushrooms Grow Kits()

Pingback: Magic Mushroom spore syringe B+ Cubensis()

Pingback: buy viagra online()

Pingback: cheap macrobid 100 mg()

Pingback: meds online without doctor prescription()

Pingback: meclizine medication()

Pingback: Vicodin for sale()

Pingback: Buy Clonazepam Online()

Pingback: buy Zopiclone online()

Pingback: Adderall for sale online()

Pingback: can you buy viagra in bali()

Pingback: Seattle Exterminators()

Pingback: خرید ممبر تلگرام()

Pingback: Seattle Exterminators()

Pingback: where to buy mestinon 60 mg()

Pingback: Seattle rats exterminators()

Pingback: Seattle Mice Exterminators()

Pingback: Exterminators near me()

Pingback: Seattle Exterminators()

Pingback: Seattle Exterminators()

Pingback: Seattle rats exterminators()

Pingback: Exterminators in my areas()

Pingback: Seattle rats exterminators()

Pingback: Seattle rats exterminators()

Pingback: Exterminators in my areas()

Pingback: Exterminators in my areas()

Pingback: Exterminators in my areas()

Pingback: Seattle rats exterminators()

Pingback: Seattle rats exterminators()

Pingback: Exterminators in my areas()

Pingback: Exterminators near me()

Pingback: Exterminators near me()

Pingback: Seattle Exterminators()

Pingback: Seattle Exterminators()

Pingback: Seattle Mice Exterminators()

Pingback: Seattle Mice Exterminators()

Pingback: Exterminators in my areas()

Pingback: private detectives agency in Madrid()

Pingback: Seattle rats exterminators()

Pingback: best erectile dysfunction medication()

Pingback: Seattle Exterminators()

Pingback: Seattle Mice Exterminators()

Pingback: Seattle Exterminators()

Pingback: Seattle Exterminators()

Pingback: Exterminators in my areas()

Pingback: Exterminators near me()

Pingback: Seattle Exterminators()

Pingback: Gelato Strain()

Pingback: Seattle Mice Exterminators()

Pingback: Exterminators near me()

Pingback: Exterminators near me()

Pingback: micardis usa()

Pingback: Organic Food Store()

Pingback: Organic Produce()

Pingback: Organic Dog Food()

Pingback: Organic Baby Food()

Pingback: Imdur()

Pingback: mobic canada()

Pingback: ed meds online without doctor prescription()

Pingback: Aciclovir for sale()

Pingback: Philadelphia University()

Pingback: motrin nz()

Pingback: Lisa Ann Porn()

Pingback: pharmacy online drugstore()

Pingback: Victoria Cakes Kenzie Reeves Lesbian Sex()

Pingback: nortriptyline 25mg canada()

Pingback: how much is viagra in canada()

Pingback: Women’s Crocodile Leather Patterned Shoulder Bag()

Pingback: how to buy periactin()

Pingback: approved canadian online pharmacies()

Pingback: how to buy phenergan()

Pingback: plaquenil 200mg australia()

Pingback: Sibil Çetinkaya()

Pingback: custom gift printing()

Pingback: prednisolone tablets()

Pingback: 3D Volume Mink Eyelashes Set()

Pingback: False Eyelashes Set()

Pingback: Women`s Professional Make up Tool Set()

Pingback: Soft Faux Mink Individual Lashes()

Pingback: Reusable Mink Eyelashes()

Pingback: Colorful Waterproof Silicone Face Cleansing Brush()

Pingback: prevacid for sale()

Pingback: Waterproof Eyebrow()

Pingback: Makeup Brushes 12 pcs Set()

Pingback: Stylish Soft Makeup Brushes()

Pingback: Professional Makeup Brushes()

Pingback: Champagne Makeup Brushes Set()

Pingback: Natural Soft Mink Eyelashes()

Pingback: prilosec 10mg prices()

Pingback: online pharmacy canada()

Pingback: Nail Polish Remover Cotton Wipes Set()

Pingback: Magnetic False Eyelashes and Eyeliner Set()

Pingback: Professional Ceramic Hair Curler()

Pingback: proair inhaler 100mcg without a prescription()

Pingback: Colorful Nail Art Dotting Pens Set()

Pingback: Mink Magnetic Eyelashes()

Pingback: Women’s Mink 3D Faux Eyelashes Set 5 Pcs()

Pingback: Eyeshadow Palette Makeup()

Pingback: procardia online()

Pingback: viagra()

Pingback: proscar without a prescription()

Pingback: Fizik Bilimi Konu Anlatýmý()

Pingback: protonix 40 mg medication()

Pingback: دراجات هوائية للبيع()

Pingback: Skyline University Nigeria()

Pingback: viagra professional()

Pingback: where can i buy provigil 200mg()

Pingback: bayviagra()

Pingback: Waterproof Lipstick Set()

Pingback: Aloe Lip Balm For Women()

Pingback: pulmicort 100mcg tablets()

Pingback: Flower Nail Stickers()

Pingback: Colorful UV and LED Nail Gel()

Pingback: Anti Aging Face Steamer()

Pingback: Disposable Eyelash Brushes Set()

Pingback: Professional Waterproof Shimmer Lipstick()

Pingback: Goat Hair Eye Makeup Brushes Set()

Pingback: amoxicillin buy online canada()

Pingback: Pearls Hairband for Women()

Pingback: Gradient Color Nail Art Brush()

Pingback: pyridium 200mg price()

Pingback: Set of 50 Metal Alligator Hair Clips()

Pingback: Black and White Disposable Lipgloss Brush 50 Pcs Set()

Pingback: Mink Hair False Eyelashes Set()

Pingback: where to buy reglan()

Pingback: Aluminium Foil Nail Polish Remover()

Pingback: Y-Shaped Facial Massage Roller()

Pingback: Disposable Eyelash Brushes()

Pingback: Crystal Nail Art Brush()

Pingback: order remeron 30 mg()

Pingback: allegra 180 price()

Pingback: retin-a cream 0.05% united states()

Pingback: revatio 20mg pills()

Pingback: where to buy risperdal()

Pingback: robaxin uk()

Pingback: rogaine 5% no prescription()

Pingback: how to buy seroquel 50mg()

Pingback: singulair 5 mg usa()

Pingback: skelaxin 400 mg canada()

Pingback: buy spiriva 9 mcg()

Pingback: viagra ingredients()

Pingback: tenormin nz()

Pingback: viagra online canadian pharmacy()

Pingback: cialis 40 mg dosage results()

Pingback: how to purchase thorazine 50 mg()

Pingback: viagra without a doctor prescription canada()

Pingback: how to purchase toprol()

Pingback: tricor 200 mg united states()

Pingback: consumer reports generic viagra()

Pingback: valtrex 1000mg purchase()

Pingback: legitimate viagra online()

Pingback: verapamil united states()